After doing the rounds in Lahore and Islamabad amidst much appreciation from the audiences, the play Lorilei - A Meditation on Loss opened at the Arts Council in Karachi, on Thursday night, with Nimra Bucha taking centre stage for the English adaptation.

As a gripping tale of sinking into despair and resurfacing with unimagined compassion, Lorilei has a higher purpose under its belt.

Buraq Shabbir

Karachi

After doing the rounds in Lahore and Islamabad amidst much appreciation from the audiences, the play Lorilei - A Meditation on Loss opened at the Arts Council in Karachi, on Thursday night, with Nimra Bucha taking centre stage for the English adaptation.

Written by Thomas Wright, Lorilei was a popular act in 2014 with Nadia Jamil and Sania Saeed at the helm of all affairs. The play seems to have resurfaced this year with Nimra Bucha stepping in place of Jamil, but it is just as heart-breaking and mind-boggling as it first appeared on the local theatre scene.

Based on the true story of Lorilei Guillory, a woman who lost her six-year-old son Jeremy, at the hands of a pedophile and murderer Ricky Langley, the play is essentially presented as a narrative, constructed from the transcripts of the actual trial, by the protagonist herself. It’s a one woman show that proceeds only through the subtle and sudden changes of her emotions and expressions. But what seems to be merely story-telling, is in fact a heartfelt outburst of her personal struggles in dealing with the loss of her son, her coming out from the depths of despair for the sake of her other child and the unexpected compassion that she develops for her child’s murderer.

Other than expressions, the play mostly thrives on words – words that describe the gruesome details of Jeremy’s murder and also words that give you a shocking synopsis of Langley’s troubled childhood. When Lorilei says, “The most important thing in Ricky’s life happened before he was born,” the audiences are discreetly being prepared to question their own moral judgments. Langley’s tale, ironically presented by his victim’s mother, is a gut-wrenching reality check that, even though at face a criminal act isn’t justifiable, it may have a justification. The justification for Lorilei is Ricky’s mental state that worsened over the years by episodes of abuse and molestation by his loved ones, pushing him to the edge of losing his mind.

The play, presented as an initiative by Justice Project Pakistan, begins with the question that is it fair to impose death penalty on a  mentally-ill person and ends with the same question; only the answers are different by the end of it all. What it really does is start a moral debate in every individual’s mind and one that has no right or wrong to it.

mentally-ill person and ends with the same question; only the answers are different by the end of it all. What it really does is start a moral debate in every individual’s mind and one that has no right or wrong to it.

Nimra Bucha is remarkable in the depiction of Lorilei’s grief, her emotional conflicts and her strength as a human being. It’s relatively difficult to perform in second language, but minor mistakes aside, Nimra does complete justice to being an advocate of an irresolvable dilemma. The varied tone and pace of her hour-long monologue is so skillfully executed that one actually feels pain in her pain; compassion in her compassion.

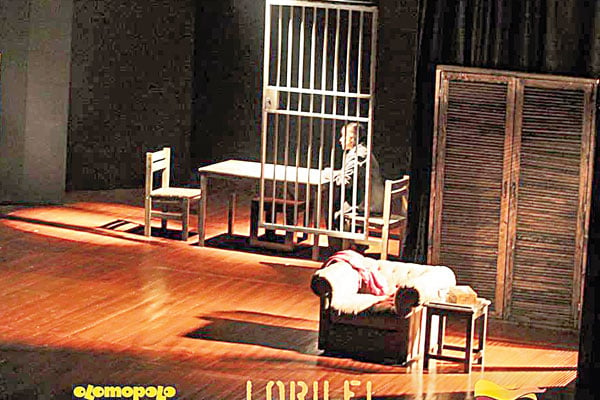

The play, however, is not without flaws in its direction. In the first half hour or so, Lorilei is only sitting on a sofa at one end of the stage causing one to lose attention after a point in time. But after a while, spotlighting the principal phases of Lorilei’s journey is what immerses one back into the story – particularly the scene where Lorilei is commentating her meeting with Langley at the Louisiana prison.

Lorilei is an unusual production but an ambitious one. Its pace is deliberately slow but its story is instantly gripping. It does come across as a bit of a stretch around the climax but as a performance art that is puzzling yet profound, with an unsettling suggestion underneath the façade, Lorilei is more than just watchable.