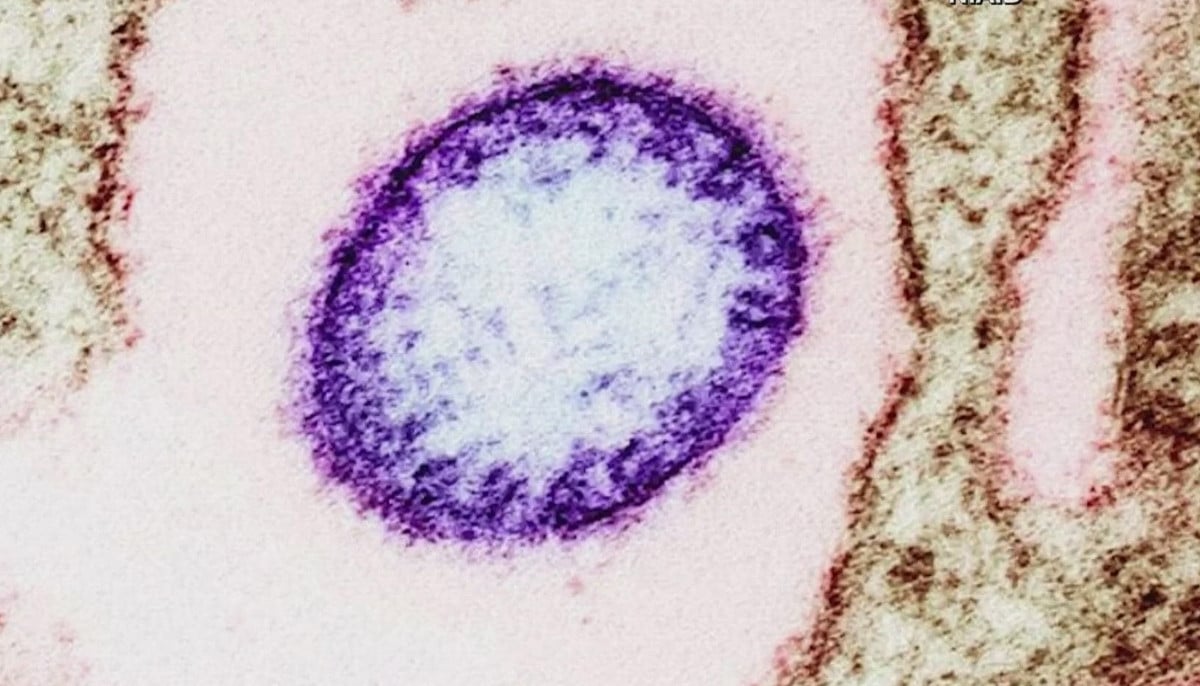

Deadly Nipah virus outbreak explained as WHO confirms infections

Nipah virus, though rare, is considered one of the most dangerous pathogens due to its high fatality rate and lack of approved treatment

Health officials are closely monitoring a deadly Nipah virus outbreak after the World Health Organization confirmed two new cases in an eastern Indian state this week.

The virus, though rare, is considered one of the most dangerous pathogens due to its high fatality rate and lack of approved treatment or vaccine.

Nipah virus is a zoonotic disease, meaning it spreads from animals to humans.

According to the US Centre for Disease Control and Prevention, infections most often occur through direct contact with infected fruit bats or pigs, or by consuming fruit products contaminated with bat saliva or urine.

In some cases, the virus can also spread from person to person through close contact.

Symptoms typically appear within four to 14 days. Early signs are flu-like and include fever, headache, muscle pain, vomiting and sore throat.

In many cases, the illness progresses rapidly, leading to brain inflammation, seizures, coma and sometimes death within days.

Respiratory symptoms such as cough and breathing difficulties have also been reported.

The virus is classified as biosafety level four, placing it in the same category as Ebola.

Fatality rates have ranged from 40 to 75 per cent in past outbreaks.

Survivors may experience long-term neurological complications, including fatigue and changes in behavior or cognitive function.

There is currently no specific treatment for Nipah virus and doctors rely on supportive care, including respiratory support for severe cases.

Prevention remains the primary defence, with health authorities focusing on limiting animal-to-human transmission and strict infection control measures.

Nipah outbreaks occur almost every year in parts of South and Southeast Asia, particularly in India and Bangladesh.

Globally, fewer than 800 cases have been reported, underscoring the virus’s rarity but also its serious public health risk.

-

Teddi Mellencamp reveals medication side-effects landed her in the hospital

-

Billy Porter claims he came back from the dead amid sepsis battle

-

Childhood obesity crisis: 220 million kids may be affected by 2040, report warns

-

Christopher Reid gives update on his ‘heart failure’

-

Paris Hilton's power move to make 'neurodiversity relatable'

-

GLP-1 drugs linked to osteoporosis and gout: New study reveals higher risks

-

Selma Blair talks about how her debilitating disease is 'misunderstood'

-

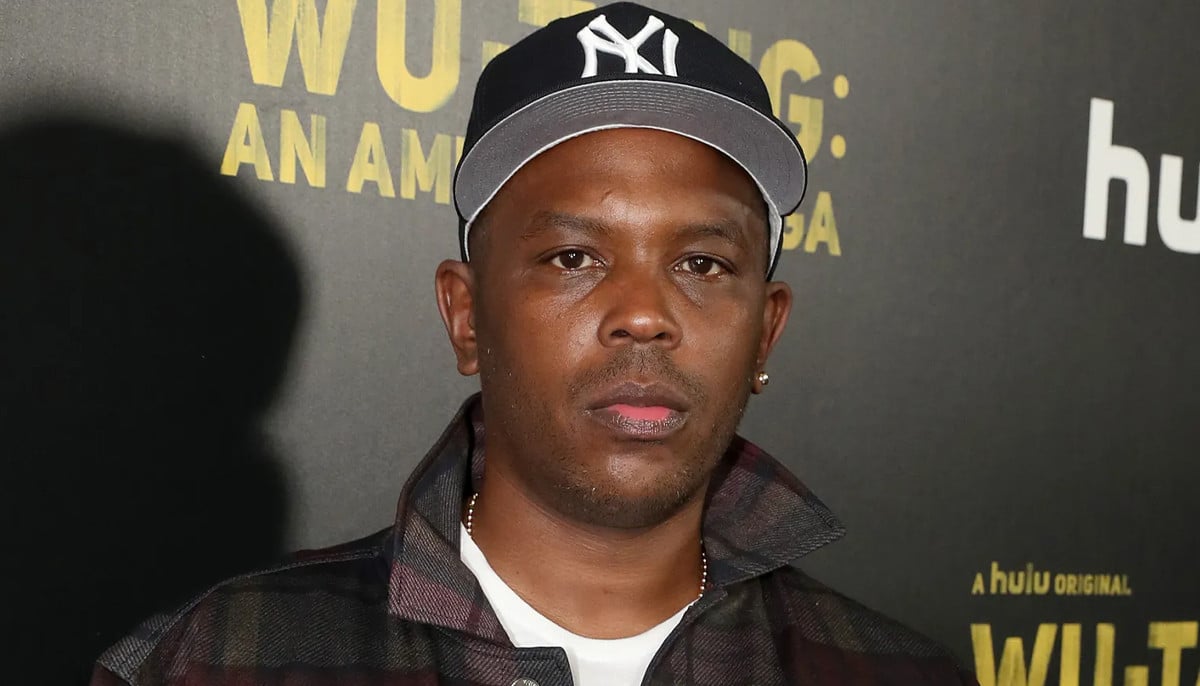

Oliver 'Power' Grant cause of death revealed