AI cameras offer new hope for endangered snow leopards and mountain villagers

Despite laws, WWF reports that 221 to 450 snow leopards are killed each year

An ambitious new conservation effort in Pakistan is testing artificial intelligence to protect endangered snow leopards and reduce deadly human-wildlife conflict. The project hopes to turn cutting-edge tech into a lifeline for both the big cats and the communities living among them.

Lovely, a rescued snow leopard in Gilgit-Baltistan, purrs rather than growls when approached. Raised in captivity after being orphaned 12 years ago, she is unfit for release. “If we release her, she would just go attack a farmer's sheep and get killed,” says her caretaker, Tehzeeb Hussain.

Globally, snow leopard numbers have declined 20% over the past 20 years, with only 4,000 to 6,000 remaining. Pakistan is home to roughly 300 of them, the third-largest population worldwide. According to WWF, up to 450 leopards are killed each year, mostly by farmers protecting livestock.

To reduce such losses, WWF and Lahore University of Management Sciences (LUMS) have developed solar-powered AI cameras designed to detect snow leopards and send SMS alerts to nearby villagers. The cameras, mounted at high altitudes, use machine learning to distinguish between humans, animals, and snow leopards.

WWF’s Asif Iqbal showcases the system, pointing to paw prints in the rugged terrain: “These are pretty new.” Back at base, he demonstrates the camera dashboard, which correctly labels him in most frames, but sometimes mistakes him for an animal. “I’m wearing a thick white fleece,” he jokes.

The cameras have recorded rare night footage of snow leopards, including a mother marking her territory. However, building this network was challenging. They had to find batteries that endure sub-zero temperatures, choose low-reflection paint, and replace solar panels damaged by landslides. While data is stored locally during outages, cellular signal issues remain.

Winning community trust proved just as tough. “We noticed some of the wires had been cut,” Asif says. “People had thrown blankets over the cameras.” Cultural norms, especially around women’s privacy, led to the relocation of cameras. Consent forms are still pending in some villages, as WWF demands safeguards to prevent misuse of footage.

Villager Sitara lost six sheep in January and questions the system’s reliability. “My phone barely gets any service during the day, how can a text help?” she asks.

Still, in villages like Khyber, local leaders note shifting perceptions. Snow leopards help maintain ecological balance by limiting the overgrazing of species. Yet some farmers are unconvinced, citing economic losses and climate pressures forcing them into leopard habitats.

WWF says legal consequences have helped—three poachers were jailed in 2020. But the organisation acknowledges AI alone won’t solve everything. In September, it will test new deterrents — lights, smells, and sounds—to keep leopards away from villages.

Though challenges persist, conservationists remain hopeful that technology can help secure the future of these elusive predators.

-

Astronauts face life threatening risk on Boeing Starliner, NASA says

-

Giant tortoise reintroduced to island after almost 200 years

-

Blood Falls in Antarctica? What causes the mysterious red waterfall hidden in ice

-

Scientists uncover surprising link between 2.7 million-year-old climate tipping point & human evolution

-

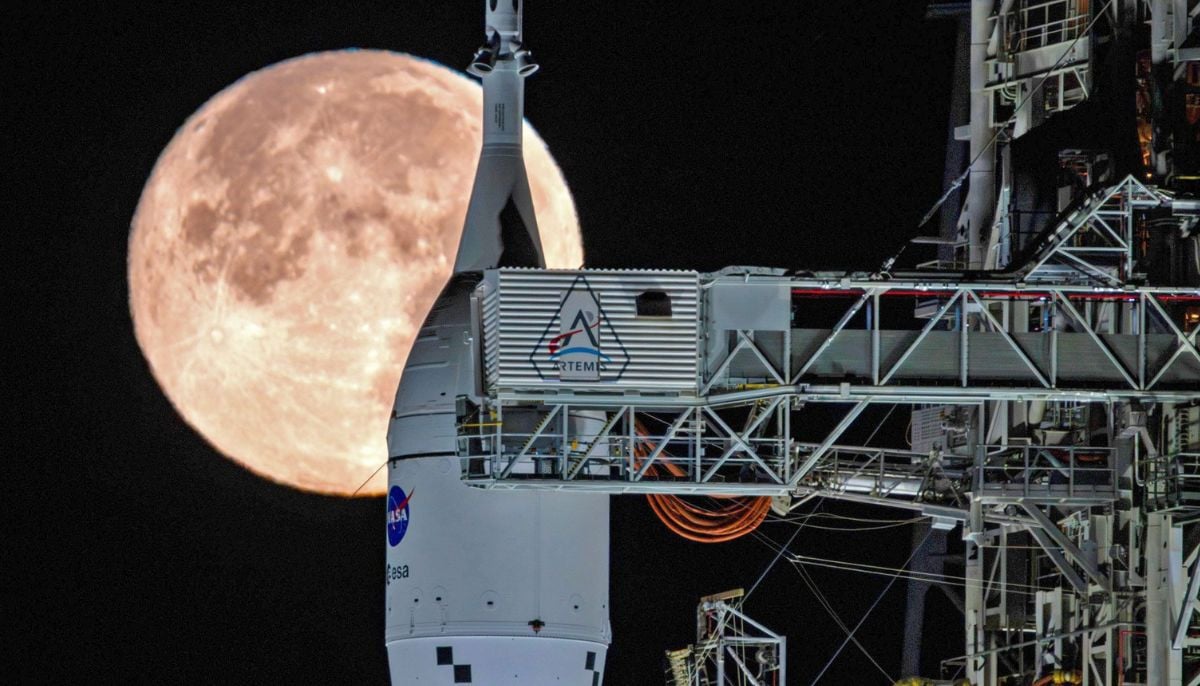

NASA takes next step towards Moon mission as Artemis II moves to launch pad operations following successful fuel test

-

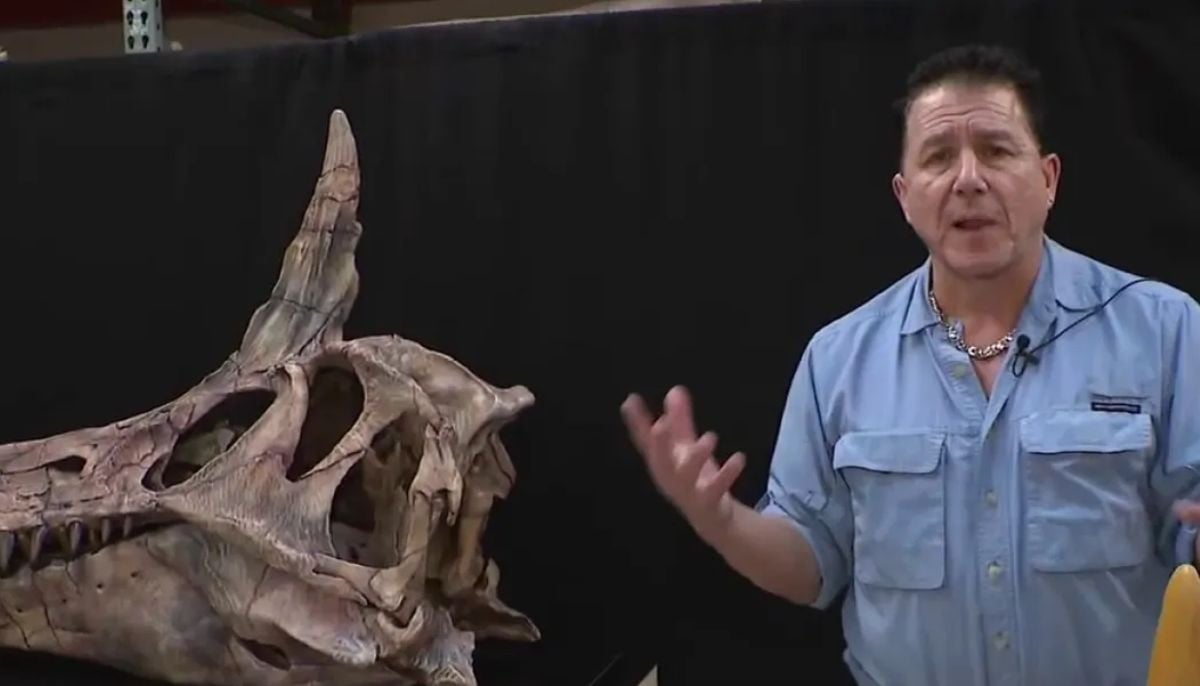

Spinosaurus mirabilis: New species ready to take center stage at Chicago Children’s Museum in surprising discovery

-

Climate change vs Nature: Is world near a potential ecological tipping point?

-

125-million-year-old dinosaur with never-before-seen spikes stuns scientists in China