Requiem for Peshawar

Peshawar needs to be pitied. In truth, every city in Pakistan is similarly choking. Western Peshawar was amazingly well-planned, (right down to Piccadilly-style shops), by the British till irresponsible ‘democracy’ arrived in the municipalities.

Today what meets the eye are ubiquitous garbage dumps, clogged sewers, missing storm drains, unplanned structures, poorly engineered roads, chaotic traffic, encroached parks, deficient drinking water and sewerage cover and much more. What the eye does not see, but the lungs and the arteries suffer, is heavily polluted outdoor (ambient) air and contaminated water.

Read also: Democracy and street protest

Centuries back, Peshawar was known as the garden city; today the shrunken Cunningham (Jinnah) park and the cantonment Company Bagh contain few traces of natural green. The major legacy of the Mughals, the Shahi Bagh, is mostly lost to brick and concrete and a mile high flag mast.

Peshawar also figures among the top twelve cities with highly polluted ambient air and chemical and microbial contaminated water quality in the world, according to Bio Med Research International. (Kabul, Lahore and Delhi take top spots).

Today, only parts of military cantonments and some enclaves retain an element of livability -- but for how long? A respected civil servant once said of Islamabad ‘the city is an aberration; enjoy it while it lasts’.

Who is to blame for the mess? The short answer: the imperious disregard of law and regulations by those in political, administrative and municipal authority. And why this disregard? The reason is the unchecked exercise of discretionary authority which led to deviation from rules for personal or party gains.

Peshawar moved towards terminal decline nearly two decades after Partition. In the early years Khan Qaiyum, the chief minister, actually brought about major infrastructural and administrative improvements which contributed to good governance. He also clamped down on the whimsical exercise of personal discretion. More recent chief ministers were not so circumspect. For instance, they allowed puncturing the ring roads at dozens of places to accommodate commercial establishments for obvious reasons.

The other factor that contributed to the city’s descent into a filthy warren of narrow streets and overflowing gutters was the humongous growth in its population. Between 1998 and 2017, Peshawar’s population doubled to two million. There was also the influx of hundreds of thousands Afghan refugees. The future looks bleak, very bleak in fact.

Peshawar faces a building space dilemma. The area to the north and west is perceived to be insecure because of the tribal (merged) areas. On the south and east lie the fertile horticulture and agriculture land and it is criminal to convert these to non-agricultural use. Clearly, there is not enough physical space, water, sewerage and garbage facilities or the social and entrepreneurial environment to provide for a population likely to rise to four million within a decade. Lawlessness and crime would be the obvious outcome with gangs and mafias in control.

Is there a solution to Peshawar’s problem? Effective governance by politicians and officials, held to account, might still provide the answer. There is also the need to discourage population influx into Peshawar by developing affordable housing and tax incentives for all district and tehsil towns to reduce the pressure on Peshawar. Simultaneously, the government needs to quickly develop land use and zonal plans to regulate existing and new habitation with emphasis on road/street widening, developing parks and high-rise parking, and upgrading drinking water and sewerage facilities.

No article on Peshawar would be complete without mentioning some monstrosities gifted by rulers to Peshawar over the past two decades.

The iconic assembly building, where the Frontier’s democracy was born, has been subjected to fearsome attacks by successive governments. As governor, General Iftikhar Shah tastelessly expanded the girth of the assembly structure, topping it with an inelegant dome, with no regard to aesthetics or symmetry. Next the ANP government, quite unnecessarily, built an elevated highway right next to the assembly building when a better alternative was placing it partially underground.

Not to be outdone, the PTI government decided to completely block the front view of the assembly building by constructing drab offices on the assembly lawns. Can these be remedied? Yes, a team of architects and aesthetes be appointed to recommend how best to reclaim the beauty and dignity of the assembly building.

And, finally, a word about the perpetual eyesore, the ‘Pervez Khattak folly’ better known as the BRT or the metro. Its design is as faulty as its utility debatable. It looks like an extended carbuncle highlighting the limits of the government’s idiocy. There was no need to copy the Lahore and Islamabad metros with an overall price tag of nearly Rs100 billion. A more sensible approach would have been to dedicate two central lanes on the wider roads to the metro, as in London, and by acquiring adjoining private land and shops where additional space was required. At a few congested commercial areas, tunnels would have provided the ideal alternate.

The ‘major flaws’ that the Asian Development Bank now pinpoints needed to be answered by their own consultants who designed the monstrosity in the first place. A hundred billion rupees was enough to put all of KP’s out-of-school children into classrooms for ten years or to build five Shaukat Khanum-quality hospitals. Is a relief possible from this ‘aesthetic pollution’ now?

The proper course lies in appointing an impartial all-stakeholders blue ribbon commission to recommend the future of the BRT. The KP chief minister owes this to the people; or else the high court may kindly look into it.

The writer works as executivedirector of the Society for the Promotion of Engineering Sciences and Technology.

Email: markhornine@gmail.com

-

Andy Cohen Gets Emotional As He Addresses Mary Cosby's Devastating Personal Loss

Andy Cohen Gets Emotional As He Addresses Mary Cosby's Devastating Personal Loss -

Andrew Feeling 'betrayed' By King Charles, Delivers Stark Warning

Andrew Feeling 'betrayed' By King Charles, Delivers Stark Warning -

Andrew Mountbatten's Accuser Comes Up As Hillary Clinton Asked About Daughter's Wedding

Andrew Mountbatten's Accuser Comes Up As Hillary Clinton Asked About Daughter's Wedding -

US Military Accidentally Shoots Down Border Protection Drone With High-energy Laser Near Mexico Border

US Military Accidentally Shoots Down Border Protection Drone With High-energy Laser Near Mexico Border -

'Bridgerton' Season 4 Lead Yerin Ha Details Painful Skin Condition From Filming Steamy Scene

'Bridgerton' Season 4 Lead Yerin Ha Details Painful Skin Condition From Filming Steamy Scene -

Matt Zukowski Reveals What He's Looking For In Life Partner After Divorce

Matt Zukowski Reveals What He's Looking For In Life Partner After Divorce -

Savannah Guthrie All Set To Make 'bravest Move Of All'

Savannah Guthrie All Set To Make 'bravest Move Of All' -

Meghan Markle, Prince Harry Share Details Of Their Meeting With Royals

Meghan Markle, Prince Harry Share Details Of Their Meeting With Royals -

Hillary Clinton's Photo With Jeffrey Epstein, Jay-Z And Diddy Fact-checked

Hillary Clinton's Photo With Jeffrey Epstein, Jay-Z And Diddy Fact-checked -

Netflix, Paramount Shares Surge Following Resolution Of Warner Bros Bidding War

Netflix, Paramount Shares Surge Following Resolution Of Warner Bros Bidding War -

Bling Empire's Most Beloved Couple Parts Ways Months After Announcing Engagement

Bling Empire's Most Beloved Couple Parts Ways Months After Announcing Engagement -

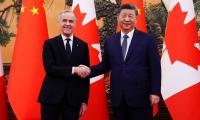

China-Canada Trade Breakthrough: Beijing Eases Agriculture Tariffs After Mark Carney Visit

China-Canada Trade Breakthrough: Beijing Eases Agriculture Tariffs After Mark Carney Visit -

Police Arrest A Man Outside Nancy Guthrie’s Residence As New Terrifying Video Emerges

Police Arrest A Man Outside Nancy Guthrie’s Residence As New Terrifying Video Emerges -

London To Host OpenAI’s Biggest International AI Research Hub

London To Host OpenAI’s Biggest International AI Research Hub -

Elon Musk Slams Anthropic As ‘hater Of Western Civilization’ Over Pentagon AI Military Snub

Elon Musk Slams Anthropic As ‘hater Of Western Civilization’ Over Pentagon AI Military Snub -

Walmart Chief Warns US Risks Falling Behind China In AI Training

Walmart Chief Warns US Risks Falling Behind China In AI Training