Death - body, mind and soul

Test yourself; draw the first image that comes to your mind when you think of death. Is it dark? Is it neutral? Are you terrified of death? Or are you extremely curious?

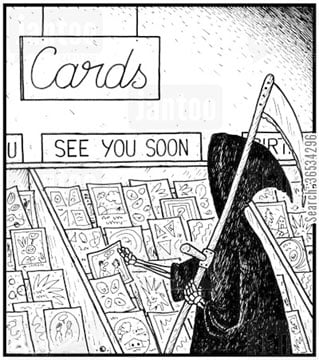

For most of us, death is a mysterious phenomenon. It’s there - we can feel it at all times, in all seasons - and yet the subject is dealt with caution the minute you are outside the cinemas. Yes, the gory details - thanks to the media - will be discussed, but not death or dying itself. It’s like a taboo; you’re shushed if you try to start a talk; since there’s nothing ‘positive’ about death, let’s just avoid it. Or, talk if you must, then use indirect hints when you mean to refer to it. Which is unfortunate. Death is an occasion like any other, be it sports, or exams. Who wouldn’t want to be prepared for it, especially when they are seeking and/or providing end-of-life care?

We can ask one another our reactions when we are in someone else’s shoes but, honestly, we may never know the effect in its entirety. Each experience is unique to each of us. Critical illness is one such experience. Whether it’s two different people or the same person moving from one stage to another, the range of behavioural reactions are far too many to be ignored: denial, difficulty with coping, difficulty adapting to changes in their lifestyle, anger and social confidence problems, etc.

What if such patients are not given the desired help and support? What if they are not told why they are receiving the treatment, meeting new doctors, coming across other patients who have similar diseases? They’ll be confused. They’ll be distressed, and emotionally conflicted. There will be hundreds of questions running through their mind. ‘What happens if I cease to exist?’ ‘What if it leaves me dependent on others?’ ‘I’m having mixed feelings (guilt and anger) about it; is this normal?’ This fear is real and humongous; this anxiety toxic and paralysing in nature. And where does that take them if not to physical and psychological deterioration?

So, why all the hush-hush?

Professionalism vs humanism: the debate

Most you might recall the film where the dean of a medical college gave this advice to newly admitted medical students: ‘Patients se dosti, hamdardi, lagao aik doctor ki kamzori hai. Aglay paanch saal tumhay ye hi sikhaya jaega kay doctor kay liye patient sirf ek beemar shareer hai aur kuch nahi.’ (Friendship, sympathy and compassion with patients weaken a doctor. For the next five years, you will be taught that for a doctor, a patient is just a sick body, nothing more.)

Very few physicians or specialists show their emotions openly. Working in an environment where masking your feelings is the epitome of ‘professionalism’, where death is a norm and where they are taught to save lives and not tend to the dying, it can admittedly be a ‘personal failure’ to break down just because they’ve seen a corpse.

‘This was my very first call. My resident had just left and almost all patients were stable. Unexpectedly, a young patient collapsed and while our CPR team rushed to save him, they were unable to do so. I was a very naïve intern who was seeing the first death of my career; it was an extremely emotionally overwhelming experience for me. I did not know how to cope. I was sitting at the counter, trying to make a death summary and I just started crying. What was [and still] is surprising that the patient’s attendants and close relatives saw me and came up to me and consoled me. They were the ones who counselled and talked to me, comforting me with banalities like: ‘nothing was wrong,’; ‘it had to happen and I shouldn’t feel guilty,’ reminisces Dr Yasmin Rashid at the 19th National Health Sciences Research Symposium, held at Aga Khan University.

The statistics she shared from a medical journal ought to be an eye-opener: less than 18 percent of students and residents who were surveyed had received formal end-of-life care education; 39 percent felt unprepared to address patients’ fears about death; and nearly 50 percent felt unprepared to manage their own feelings about death.

It is catastrophic!

Especially knowing that ‘the profession of nursing is deeply rooted in emotions, compassion and empathy.’ As David Arthur stressed in one of the panel discussions, ‘[it is a matter of] concern these days [that] we aren’t getting as close to people as we could do therapeutically. In medical profession, we are not using interpersonal relationship to the fullest degree.The world is changing; patterns of healthcare are changing. We can really emphasize the nature of human relationship.’

Maybe it is the fear of making yet another incorrect diagnosis or fear of medical liability suit carried forward from a previous encounter that does not encourage emotion-based decision-making. Maybe, it’s too much of hope even. They would rather not be vulnerable, and prefer spending more time with their computers and smartphones than making eye contact while taking to the patient. But here is what makes emotions a critical part of treatment: the desire to help fellow human beings, the love for them to have exact diagnosis and cure. How does one make a life-altering decision if, despite all their knowledge and experience, they do not feel compelled to act?

And while physicians and nurses try to balance this inner conflict by pretending to be immune and trying to be all rational and, truth is they are not machines relying on logic only. The methodical and the impulsive, the right and the left brain, must go hand in hand. Sure, staying constantly busy, smoking, overeating, using recreational drugs, etc. are great options when you want to suppress or intellectualise emotions. Anything to not feel, not process, the feelings. Thing is, feelings denied don’t go away anywhere; they’re present at all times, waiting for their chance, and in the meantime, they change the present behaviour. If the doctor is disconnected from his/her reality and not honest to their own self, how is it that they can take a balanced decision?

Besides, the person - or the approach to improve his/her health - cannot be compartmentalized. It’s not like a serious illness is affecting the physical body only; there are other systems functioning, all sorts of chemical reactions that are influencing the patient, too. When we think about it for a moment, we ourselves would prefer someone who is not just a master of craft, but also a person who has mastered the art of communication, someone who is deeply concerned and caring when it comes to his or her patients, someone who would prioritise the patients’ interests above everything else. We want the doctors in charge of our case to believe in patients’ right to accurate information rather than using distancing tactics, simply because words like ‘death’ or ‘dying’ freaks them out! Saying ‘time could be very short - a few weeks or a few months; it’s advisable to prepare for the worst and hope for the best’ instead of ‘you are dying’ might not generate stress in the doctor, but it certainly wouldn’t allow the patients to deal with their situation in a better way! Not having long, honest discussions might be your strategy to not get close to the patient, but it can easily be the very reason why patients who are misguided and have no other source of information don’t navigate well through their end-of-life journey! There’s a study that suggests such patients choose a less-aggressive therapy - aimed to make them feel better and not live longer - if the doctors discuss the options with them at least a month before the death.

Besides, the person - or the approach to improve his/her health - cannot be compartmentalized. It’s not like a serious illness is affecting the physical body only; there are other systems functioning, all sorts of chemical reactions that are influencing the patient, too. When we think about it for a moment, we ourselves would prefer someone who is not just a master of craft, but also a person who has mastered the art of communication, someone who is deeply concerned and caring when it comes to his or her patients, someone who would prioritise the patients’ interests above everything else. We want the doctors in charge of our case to believe in patients’ right to accurate information rather than using distancing tactics, simply because words like ‘death’ or ‘dying’ freaks them out! Saying ‘time could be very short - a few weeks or a few months; it’s advisable to prepare for the worst and hope for the best’ instead of ‘you are dying’ might not generate stress in the doctor, but it certainly wouldn’t allow the patients to deal with their situation in a better way! Not having long, honest discussions might be your strategy to not get close to the patient, but it can easily be the very reason why patients who are misguided and have no other source of information don’t navigate well through their end-of-life journey! There’s a study that suggests such patients choose a less-aggressive therapy - aimed to make them feel better and not live longer - if the doctors discuss the options with them at least a month before the death.

The sad reality of our social setup is such that sometimes it’s the patient’s “well-wishers” who ask the doctor to not discuss these things directly with the terminally ill individual.

Respecting wholeness of life

To be honest, gaps exist due to negative attitudes and myths surrounding such communication: patients will blame me; patient is going to break down; a colleague or resident should inform the patient; a doctor should tell them very quickly to get over it. Wrong.

When you talk to them, you need to wait and listen, to give them some time and hope for the near future. There’s no standard when it comes to being the messenger and bearer of bad news, but there are practical suggestions to anyone who’s interested:

a) Initiate discussions by talking about some personal stuff, like patient’s spiritual preferences, familial situations;

b) Share the truth step by step, according to the patient’s ability to bear with it;

c) Divulge information when there’s time;

d) Discuss in a comfortable and safe place (e.g. office);

e) Involve patient’s family and ensure their presence when the truth is disclosed.

Death changes relationships - with parents, children, relatives and friends. Loss of a child is an even more difficult event for the family and the physician. In that instance, communication plays an important role. The terminally ill children should be informed about the gravity of their illness; parents who request otherwise should know how isolated such children feel otherwise. In fact, his or her siblings should also know about the disease, too, and be allowed to participate in the care programme; this way, they can make sense of the death in the months leading to and after it. Parents, on the other hand, who perceive child’s death as good, have fewer or no regrets. The doctors, obviously, would respect whatever decision you come up with.

Accepting death - is it possible?

Did you know that your fixation with a particular aspect of death - biological, psychological, social, cultural - actually determine the way you live your life? And that in order to die well you also have to live well?

Yes, death is a multi-dimensional construct. So, if there’s a person dying right in front of you, you need to keep their various needs in mind as well. And, if the patient has been uncertain in matters of life, chances are issues like unfinished worldly affairs (e.g. a will, an unmarried daughter, old parents) or loss of self, or pain/loneliness that comes with time spent in clinics will create a total chaos in mind. Alternatively, there have been instances where ‘something hits them’ and they suddenly get disconnected from the mania of their life; that’s when dying can be considered a time of reflection, personal freedom and growth.

A patient would constantly shift back and forth between the stages of denial (avoidance), anger (aggression), bargaining (praying to God) and depression (social withdrawal) until they reach the stage of acceptance. Interestingly, here too the patient is suspended between facing death very rationally as an inevitable end of every life (neutral death acceptance), seeing death as a gateway to a better afterlife (approach death acceptance) and choosing death as a better alternative to painful existence (escape death acceptance).

This is when the process of dying really begins. However, for every mother who is waiting for reconciliation with her estranged daughter, for every father who’s thinking how to hand over the responsibility to his son, every woman to overcome a sexual trauma by forgiving the deceased perpetrator as they come to the end of their own lives, there is some patient who would take up a defensive position and not come to terms with reality. They would enter a state of severe neurosis.

What we need to understand here is there are different pathways of acceptance. For one, some people are willing to let go, recognising the spiritual connection and transcendent reality; some opt for the terror management model (wherein avoidance of death anxiety is the primary motive) while others take to meanings management model.

Being around a dying person doesn’t mean you cannot create a meaning out of the adverse experience with them. Death is our best teacher and death acceptance the best antidote to death anxiety. For now, doctors can begin by listening to patient’s fears, pain, hopes and dreams. Meanwhile, the rest can make do with ‘death cafes’ and ‘dying dinner parties’ where people are opening up about their respective precious times; it offers a compassionate, respectful and intimate environment and the participation itself is uncensored and inspiring.