Moving towards ’93 once more?

General Waheed Kakar was an accidental chief of the Pakistan Army. After Asif Nawaz’s death, there began a tug between the then president Ghulam Ishaque Khan and the then prime minister Nawaz Sharif, to have their own man appointed to the position.

The president then was empowered by the extraordinary clause 58(2)(B) of the constitution that enabled him to dismiss a prime minister and his government, and parliament, if he felt they weren’t functioning in the interest of the state.

With neither submitting to the will of the other, in full public glare, both agreed on a rather little-known Waheed Kakar, who was preparing for retirement. He too was a Pakhtun as the president, and GIK may have sighed a sense of relief on at least having a fellow-Pakhtun in the battle of power between the PM and the president.

Ziaul Haq, under whom GIK had risen to eminence, had included 58(2)(B) in the constitution, so having one’s back by another army chief when faced with a challenge to this all-powerful clause was just such a nice thing.

Under 58(2)(B) the president was inevitably ‘the state’, and could contrive causes to dismiss a government and a prime minister. GIK had already pocketed the government of Benazir Bhutto under this clause. NS attempted to denude the president of this draconian authority and was already on the wrong side of GIK. And when GIK dismissed NS’ government too, NS invoked the Supreme Court which favoured restoring NS back into power.

This battle between the two brought the government and the state into abysmal dysfunction. Two men on the back of a controversial clause in the constitution, and because of it, held the state and the nation at ransom even as they feuded over power. When the pantomime had gone on for a bit long, Waheed Kakar intervened and, being the moment’s ‘man on the horse’, asked both to ‘turn in their papers’. GIK was consigned to the dustbin of history while NS was replaced by the ever-ready BB in yet another premature election in Pakistan’s turbulent march towards democracy.

The controversial clause, however, stayed; and BB’s own presidential appointee used it against her in 1996. It was only in another era of the PPP, in 2010, that 58(2)(B) was finally seen off – restoring some sanity to Pakistan’s constitutional structure, but not to Pakistan’s political culture.

Fast forward to 2016, and trust the Pakistani politicians to create a situation where there is none. The Panama leaks haunt NS. Not the army chief, not the chief justice, not another demonic constitutional clause, but he himself, through his own doings and those of his uber-rich family, has brought this upon him. As he struggles with questions of his credibility and fidelity as prime minister, he appears increasingly beleaguered and emaciated as head of government. As he puts up a brave face to the growing din of his culpability, hoping this too will pass, he remains particularly vulnerable given the fundamental nature of the issues at stake.

And these are as fundamental as they come: is Pakistan’s ruler corrupt to the core? Can such a man continue to be at the helm of a nation that sits at a moment in history when it is fighting an existential battle for its survival in attempting to bring the demon of terror in control? And perhaps foundational to the future of the hapless Pakistanis: do they have ‘any’ control over who sits atop them and plunders at will without the slightest whimper in legal or procedural checks on such lustful drawings from the nation’s resources?

For the moment all eyes are on the chief justice. Will he be the man of ‘this’ moment? That remains to be seen. He has to answer the above questions on behalf of the people of this country. Going by the signs the CJ is unlikely to get ‘honest’ answers. He may get legally correct answers but not honest answers. The moment demands honest answers. And if he can dig those through from the heaps of obfuscation he may well set the course of a better future for the people of this country.

Imagine all those who were thinking of bringing their money into Pakistan in the wake of the great opportunity that the CPEC was to create, and now their moment of uncertainty, not knowing who they were dealing with. Our prime minister should be seen to be above board and known as such. He cannot mix skulduggery with governing the future of two hundred million people.

And now that dreaded 1993 moment. The chief justice reaches the root of the problem, finds his prime minister in the wrong, and having so determined comes across a wall of denial from NS on his culpability. Hop over across to the GHQ. A chief who is revered to the point of deification, knows it too and has invested in himself the popular responsibility to do good on behalf of the people – for that is the mantle the combined wisdom of the nation has raised him to – takes it on himself to intervene and rectify the resulting dysfunction. The two then, CJ and the army chief, come together again in a sad repeat of 1993 and usher yet another political transformation.

Just that this time it shall not be another demonic dictator but the political character that will have to take responsibility for a course correction that was desperately needed but thoroughly missed in our democratic journey.

The question is: does Raheel Sharif have that last act left in him? Going by how he has spaced his achievements, there still is time for that last Hurrah. Following which he can simply fade away into the setting sun on the back of his horse. Who gives up on such deification? There is still time though for the politicians to come clean, save the system and forever shed the grime. Depends who is more desperate for what.

The writer is a retired air-vice marshal, former ambassador and a security and political analyst.

Email: shhzdchdhry@yahoo.com

-

Apple Developing AI Pendant Powered By In-house Visual Models

Apple Developing AI Pendant Powered By In-house Visual Models -

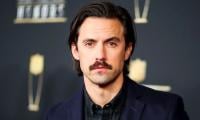

'Gilmore Girls' Milo Ventimiglia Shares How He Would React If His Daughter Ke'ala Coral Chose 'team Dean'

'Gilmore Girls' Milo Ventimiglia Shares How He Would React If His Daughter Ke'ala Coral Chose 'team Dean' -

New AGI Benchmark: Demis Hassabis Proposes ‘Einstein Test’—Ultimate Challenge To Prove True Intelligence

New AGI Benchmark: Demis Hassabis Proposes ‘Einstein Test’—Ultimate Challenge To Prove True Intelligence -

NASA Artemis 2 Moon Mission Faces Unexpected Delay Ahead Of March Launch

NASA Artemis 2 Moon Mission Faces Unexpected Delay Ahead Of March Launch -

Kate Middleton Reclaims Spotlight With Confidence Amid Andrew Drama

Kate Middleton Reclaims Spotlight With Confidence Amid Andrew Drama -

Lady Gaga Details How Eating Disorder Affected Her Career: 'I Had To Stop'

Lady Gaga Details How Eating Disorder Affected Her Career: 'I Had To Stop' -

Why Elon Musk Believes Guardrails Or Kill Switches Won’t Save Humanity From AI Risks

Why Elon Musk Believes Guardrails Or Kill Switches Won’t Save Humanity From AI Risks -

'Devastated' Richard E. Grant Details How A Friend Of Thirty Years Betrayed Him: 'Such Toxicity'

'Devastated' Richard E. Grant Details How A Friend Of Thirty Years Betrayed Him: 'Such Toxicity' -

Rider Strong Finally Unveils Why He Opposed The Idea Of Matthew Lawrence’s Inclusion In 'Boy Meets World'

Rider Strong Finally Unveils Why He Opposed The Idea Of Matthew Lawrence’s Inclusion In 'Boy Meets World' -

Who Was ‘El Mencho’? Inside The Rise And Fall Of Mexico’s Most Wanted Drug Lord Killed In Military Operation

Who Was ‘El Mencho’? Inside The Rise And Fall Of Mexico’s Most Wanted Drug Lord Killed In Military Operation -

Tom Cruise, Nicole Kidman Mend Their Relationship Following The Murder Of Rob Reiner, Wife Michelle Reiner?

Tom Cruise, Nicole Kidman Mend Their Relationship Following The Murder Of Rob Reiner, Wife Michelle Reiner? -

Kate Middleton May Break Because Of Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor & Expert Speaks Out

Kate Middleton May Break Because Of Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor & Expert Speaks Out -

Celebrities Who Struggle With Infertility

Celebrities Who Struggle With Infertility -

Is Social Media Addiction Real? Experts Explain Signs And How To Cut Back

Is Social Media Addiction Real? Experts Explain Signs And How To Cut Back -

Can App Stores Really Keep Kids Off Social Media? Here’s What Experts Says

Can App Stores Really Keep Kids Off Social Media? Here’s What Experts Says -

Margot Robbie Fears Being Dubbed A 'dumb Blonde' Due To Major Reasons: 'Hates The Idea'

Margot Robbie Fears Being Dubbed A 'dumb Blonde' Due To Major Reasons: 'Hates The Idea'