Imagine if we still communicated through sign language like our cave-dwelling ancestors, life would be so different - not to mention difficult. We should be thankful to those who invented easier ways to communicate and we progressed from miming to actual sounds that later developed into words and languages.

COVER STORY

Imagine if we still communicated through sign language like our cave-dwelling ancestors, life would be so different - not to mention difficult. We should be thankful to those who invented easier ways to communicate and we progressed from miming to actual sounds that later developed into words and languages.

We may be losing the art of vocal communication - at least in real time - due to the internet and use of smartphones with different aaps that allow us to communicate in the cyber world. But the importance of language cannot be diminished. It would be extremely difficult to communicate even in the cyber world without words.

Fortunately, we have languages to communicate with each other - and it is possible that in the coming years the language ‘spoken’ in the cyber world will also be ranked among the most important languages in the world.

There are many languages in the world but only a handful used to bridge the lingual gap between people hailing from different countries. Urdu is one of these languages, spoken by more than 100 million people all over the world. Other major languages spoken are Mandarin and English.

As far as languages are concerned, Urdu is relatively a new language born on the Indian subcontinent around the end of the 12th century. And, it is spoken in most parts of the world - UK, USA, UAE, Africa but predominately in Pakistan and India.

Urdu was originally known as Hindvi; Zaban-e-Hind; Hindi; Zaban-e-Delhi; Rekhta; Gujari; Dakkhani; Zaban-e-Urdu-e-Mualla; Zaban-e-Urdu, or as we now know it, just Urdu. It has an interesting evolution with its origins in the army camps and bazaars of the Indian subcontinent during the Muslim rule.

Urdu was also known as Hindustani and in the early years after partition people who spoke this language were known as Hindustani - of course this was also because they migrated from ‘Hindustan’ or India.

People from different countries came down to the rich Indian subcontinent and interacted with different people. They needed a common language to be able to speak to each other, and the basis of Urdu were laid. It was a language which absorbed words from other languages.

It is part of the ‘Indo-Aryan’ group of languages and emerged as a language with heavy influence from other major languages spoken at the time primarily Persian - the language the Muslims brought with them - and Hindi - the language of the local population.

An interesting point about this language that emerged in the Indian subcontinent is that it is closely related to Hindi as Urdu has many similarities in phonetics and grammar.

Many people think that Hindi and Urdu are the same language while others believe they should be considered to be two languages. However, since Urdu emerged and developed under the influence of the language of the court - Persian - of India the structure of the language is essentially Indian but the vocabulary reveals a greater influence of Persian.

Urdu has major Arabic and Persian influences and uses a modified Perso-Arabic script, while Hindi has more Sanskrit influence and uses Devanagari and this is major reason why they are treated as different languages.

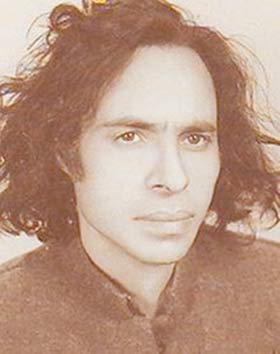

Renowned poet and writer Jon Elia commented on the way Urdu was evolving even though he was not too happy with this process. He said he was a lingual aristocrat who abhorred change and especially hated the way Urdu was evolving. “I do not like the way Urdu is evolving in today’s world; this is basically because most people are uneducated. Even the teachers teaching this language are illiterate and they are the main reason the language is in the bad state it is today.

“But, despite this, we cannot stop Urdu from constantly changing, and many words have been added over the years that are from other languages. I don’t like this change but I cannot stop it from evolving as the usage changes.” Elia added. “For example, my mother’s generation used the words that were from other languages. I come from a family proud of its impeccable Urdu but even we were constantly using words from other languages that had become part of Urdu. My mother, for example, used words like ‘almari’ which was a ‘Hindi’ word which has become part of the language via Portuguese from Latin armarium which means ‘closet, chest’.”

Elia may have been upset about this but even he could not stop words from different languages becoming part of the language. He said that this was how languages died and then became extinct and he was afraid Urdu would also meet the same fate.

But scholar and poet of Urdu Rais Amrohvi saw the evolution and development of Urdu as an inevitable process that every language goes through.

“There are always two versions of every language. One is pure language restricted to a small clique of people comprising writers, thinkers, poets and scholars; the other is the one spoken by the masses, which is usually a simplified version and which has many additions and subtractions from the original language. This is not a new language but a modified version of the same language.”

Apart from being well-versed in Farsi (Persian), Arabic and somewhat in Sanskrit, Amrohvi had been self-taught in English and Sindhi and had translated the works of Bulleh Shah’s works into Urdu. Therefore, he was aware of the structure and usage of different languages.

“Urdu has also evolved over the centuries - once predominately influenced by Persian and Arabic mainly because these languages were part of everyday life and education, the language had a large number of words from them. After the Europeans presence, the word took many words from the different languages and people started using these words.”

Amrohvi added that languages keep evolving with the needs of the time, pointing out that Urdu had many words from English mainly because it was an important language to learn in the world today. He said there are many English words that have replaced words in Urdu - but because these words are ‘easier’ to use or because people want their children to learn them they have been included in everyday use.

And sure enough we see many words that have become part of Urdu we speak every day. This is seen as parents intentionally introduce English words in the children’s vocabulary at an early age; this trend is supported by the fact that pre-schools expect children to know certain English words at admission.

Many words that are used commonly like glass; cup; ‘phone’ (mobile and cell included); ‘almari’; ‘bathroom’; ‘botal’ (bottle); ‘cupbard’ (cupboard); TV; radio; AC; building; bus stop; school; airport; hospital; medical store; doctor; emergency; police; ambulance; park; gym; traffic light; light; tube light; table; sofa; bag; shoes; internet; office; school; cable; purse; cigarette; furniture; blackboard; shampoo, etc. have become such an integral part of Urdu that even people with no basic education use English words without being aware that these are not originally words of their native language.

However, this whole process of change and evolution has its negative points as well. With the focus on adding words in the vocabulary, we have lost interest in retaining the quality of the language as it is taught in educational institutions.

Urdu teachers, just like teachers of other languages in Pakistan, are not trained to teach this most difficult subject. There is very little training for language teachers and they are the lowest paid of their group.

Most teachers are recruited only on the criteria that Urdu is their native tongue, and the fact that they have no idea about the language, grammar and usage and most importantly the pronunciation of different words is conveniently overlooked. No one seems to notice this flaw and children are taught the wrong pronunciations.

This is also seen in the Urdu tickers on our channels. Some of these spellings are so painfully wrong that it is amazing they are allowed to be aired. Every channel should have a panel of scholars or teachers who can keep conducting refresher courses for those responsible for the script, especially tickers. This is important as this content reaches a large number of viewers, mostly young, and it is the media’s responsibility to teach the right thing to them.

Another important thing that seems to be overlooked is the spellings of the teachers, who have seldom read any classics of the la nguage and have ‘taught’ themselves to write by reading digests that comprise their libraries or movies - mostly Hindi movies. Their only ‘brush’ with the great poets and writers of Urdu was probably during their own student years, where excerpts of the great works are sometimes included. They are not encouraged to read more of the greats of the Urdu language apart from the curriculum. This meagre exposure to Urdu literature is a major flaw and a disadvantage for their students.

nguage and have ‘taught’ themselves to write by reading digests that comprise their libraries or movies - mostly Hindi movies. Their only ‘brush’ with the great poets and writers of Urdu was probably during their own student years, where excerpts of the great works are sometimes included. They are not encouraged to read more of the greats of the Urdu language apart from the curriculum. This meagre exposure to Urdu literature is a major flaw and a disadvantage for their students.

Speaking of Hindi movies, interestingly the Hindi that is used in these movies seems to have more Urdu words in it and in a way these movies are doing a great service to the spread of Urdu as a language. Many foreigners have picked up this language from these movies.

Our students consider English to be a relatively easier language than Urdu - and other languages of the country - mainly because they have more exposure to the language supported by the efforts of their parents and teachers from an early age.

Students are either bored or intimidated by the Urdu language - sometimes it is the teacher and sometimes it is the text they are reading, which is responsible for their lack of interest in Urdu. There is a dire need to train and teach teachers who are involved in teaching languages especially ‘difficult’ languages like Urdu.

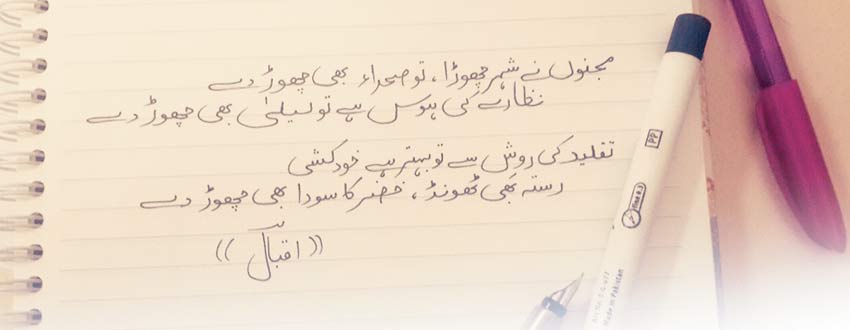

Interestingly, we see more work being done in Urdu in India, the US, Germany and Canada - to name a few - than we see in Pakistan. Great poets like Ghalib and Mir are a few that survived the onslaught of time mainly because these have been included - in small quantity - in our textbooks. We will have to commend the work that Indian film makers have done to preserve the original Urdu through various films like Ghalib, Umarao Jaan, etc.

We cannot expect others to keep doing our job it is time that Pakistan paid attention to Urdu, since Urdu is our official national language. It is our duty to improve the standard of the usage of this language. More scholars need to work on this language introducing easier and interesting methods to teach this language to our students.

Roman Urdu - a curse in disguise

“Khana baney EXCITING”

“Hamesha agay”

“Fun ka daily dose”

You were able to read each of them, right? These aren’t random words that I chose as examples; you recognize them all too readily as the ‘creative wordplay’ visually polluting our environment amid the wide billboards spread across your city. Whether they had a soaring business is a different story. What we are here concerned with is the exposure our generation has to such language.

The trend adopted to sell the goods would have been torturous for Shakespeare even, who was known for inserting unique rhetorical devices to put forth a point. Using Roman script makes the content accessible to those who understand both languages, especially in a country like ours where the two are common.

Perhaps it would have been better curbed if the masses could not comprehend what, for instance, ye pen hai (this is pen) meant not just because it differed on basis of ‘standard’ spelling, but because they could not speak/read the Urdu language itself to know what the transliterated version was. Why do I think this way? What’s so bad about Urdu written in English pattern?

One thing: it has unfortunately done more damage than good as exhibited not only by our day-to-day conversations via SMS or social media, but also within the examination halls themselves. The habit to take mix and match words as per the context is so finely ingrained in the society that most students don’t realize the importance of using proper language - grammar, phonetics, and dictation all together - when turning in their assignments. They can’t even be bothered to say what they want in the proper code.

There is no harm in knowing different languages. In fact, it is quite possible that your mother tongue be entirely different than the one(s) you are fluent at as evident from how your mind automatically processed the taglines quoted above without finding it offensive.

People who are pro-Romanised Urdu would tell you nonchalantly it’s at least better than the burger-speak that is neither Urdu nor English. I wonder whether they would still defend it given its manifestation in important circumstances. This includes misspelt words such as ‘inaugration’ instead of ‘inauguration’ etched across a plaque, which was recently unveiled at Karachi’s hockey club. Guess what, this error is the way we both speak the word out loud and write it while conversing in Urdu.

It was only last year that the Supreme Court of Pakistan conferred the official status to Urdu language at provincial and federal levels, the notice implying that this was a language many officials felt “entirely comfortable with”. And that is true for laypersons in Pakistan who, despite having another mother tongue, are quick to get the hang of the language.

Why, then, have I been blabbing about this ‘issue’ that our society should look into? Urdu is easier to speak than write which makes it easy for the youth today to adopt Roman script for Urdu language; to not be bound by cultural rules or boundaries. It pains me to say it, but this isn’t impressive, artistic, or even part of your identity.

There are some solutions that can actively have the intended outcome for children. For instance, bilingualism is an option; expose them early to both languages. Code-switching is acceptable at times, but for the sake of saving Urdu from distortion, it is essential that you:

n Speak to them in Urdu;

n Appreciate and take pride in it;

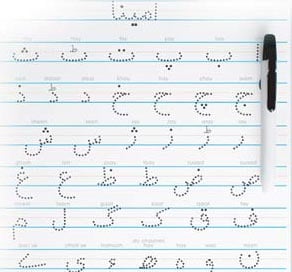

n Provide them reading material to improve their ability to comprehend Urdu and identify proper usage; the Urdu Qaida app launched by IBA, Sukkur, is a good initiative to create an impression as is the Dheere Bolo project;

n Let them watch movies;

n Enrol them in a good schooling system with skilled teachers and a motivating environment;

n Teach them words, especially those that are equivalent of English.

That sounds...what, redundant? Maybe because it’s easier said than done. As a nation, we’re still guilty of modifying the language in order to meet our needs. If we can think completely in Urdu, speak in Urdu, can we not try and write in Urdu too for expressing it successfully?

-S. Zuberi