The silliness of it all, the cruelty of it all!

On the same evening the World Cup 2019 title was being decided in London at the Lord’s, another title, the most prestigious lawn tennis title, was also being decided in London at the Wimbledon Centre Court. Both the contests went down to the wire. Both the contests were initially tied and then tied again in the next stage.

At Wimbledon Centre Court, the tie was broken in a tiebreaker played in a contest with racket and ball on the court between the contestants that decided the winner. Not so at the Lord’s. There was no tiebreaker played with bat and ball on the ground. Instead, it was decided in the remote ivory tower where lay some selected statistics. And one statistic, that is, the number of boundaries hit by the two teams, separated the winners from the losers.

It was not only silly and absurd but also arbitrary. Why number of boundaries? Is there no premium on the ability to take sharp singles, the ability to convert singles into twos? After all, it is the aggregate of runs, however scored, that determines the respective totals of the two teams.

Then, cricket is not only about batting and runs, it is as much about bowling and wickets. Look at these Vital statistics of this final:

Honours England NZ

Total Runs 241 241

Boundaries 24 16

Wickets lost 10 8

Maiden overs 1 4

England hit 50 percent more boundaries than did New Zealand. In terms of bowling and wickets, however, England were inferior — they lost 25 percent more wickets and bowled 75 percent less maiden overs.

Thus, this referral to an isolated statistic rendered the criterion to decide the winners so palpably arbitrary.

If, at all, a referral is to be made to statistics it should be holistic, not partial or isolated.

In the Wimbledon final, when the match was tied at two sets all, the match was extended to a ‘final set tiebreaker’ of up to a maximum of 12 games during which whoever won two consecutive games would be the winner. As it happened, even this did not break the tie as the score was 12 games all. At that stage, they did not refer to statistics but they went back to a regular tiebreaker which Djokovic won 7-3.

It would be both interesting and relevant for the reader to know that if the Wimbledon final had been decided on statistics, Federer would have won on most counts. Look at some of the metrics:

Djokovic Federer

Aces 10 26

Games 32 36

Points 204 218

Win% on 1st serve 74 78

Win% on

2nd serve 56 56

The Wimbledon final is an interesting case study, effectively demonstrating that the outcome of a match can be at odds with the statistics even when those are so overwhelmingly tilted in the other’s favour. This is so because all points are not equal or let’s say do not work out to be equal; statistically, one might have won more points but the other won more of the crucial points that decided a game or a set.

The most popular sport in the world, football, does not take recourse to statistics in deciding tied matches. Matches that are tied at the end of regulation time and overtime are decided through penalty shootout. Since its introduction in 1978, 30 World Cup games have been decided through penalty shootout, including two World Cup finals.

Silly as the criterion was for deciding the winners of the World Cup final, no less silly were several other incidents that left a funny taste in the mouth, to put it euphemistically.

As it happened, all these incidents went against New Zealand.

Jason Roy was factually dismissed first ball of the innings, LBW, but the umpire did not declare him ‘out’. The umpire’s original decision of ‘not out’ was duly reviewed; it revealed that the ball was actually hitting the leg stump, and, in the normal course, would be ‘out’; however, in the case of referral by the bowling side, the ball needed to hit the wicket with its full face and not less than half as was the case here; further, it would have been given LBW had the umpire’s original decision was ‘out’ and the review was sought by the batting side. Could silliness go any farther?

At the Wimbledon Centre Court, whenever a review was sought by either player, it was decided on the basis of whether the ball was actually touching the line, regardless of whether it was touching fully or fractionally and regardless of which player had sought the review.

Ross Taylor, one of the star New Zealand batsmen, was adjudged LBW by the umpire but New Zealand could not seek a review as they had used their only review available. The TV replays clearly showed that Taylor was not out. In an innings spread over 50 overs with a duration of nearly three hours, this limitation of one review is frustrating and can have a telling effect on the outcome of a match.

During the 50th over of the innings, Ben Stokes accidentally knocked the ball coming in from deep mid-wicket fielder and deflected it to the third man boundary while attempting to dive for his crease with an outstretched bat.

After consultation with Marais Erasmus, Kumar Dharmasena signalled six runs, meaning that England, who by then seemed to be drifting out of contention, needing nine runs from three balls, were suddenly right back in the game, needing three from two.

Former Australian umpire Simon Taufel has described the costly ruling in the World Cup final as a “clear mistake”. England should have been awarded five runs, not six. England’s Adil Rashid should have faced the second-last ball, not Stokes. “It’s a clear mistake and it’s an error of judgment,” Taufel told foxsports.com.au.

However, the ICC said the umpires took decisions on the field based on their interpretation of the rules, and the cricket body would not comment on the episode.

In summary, New Zealand were at the receiving end of the stick in all the listed cases, while ‘the boundary countback rule’ was the final nail in the coffin.

Williamson did not crib or complain. His reactions were those of a veritable gentleman of the “Gentlemen’s game”. Reacting to the overthrow runs controversy, he said, “I actually wasn’t aware of the finer rule at that point in time; obviously you trust in the umpires and what they do. I guess you throw that in the mix of a few hundred other things.”

When asked about the boundary countback rule, he said: “I suppose you never thought you would have to ask that question and I never thought I would have to answer it (smiling).

“While the emotions are raw, it is pretty hard to swallow when two teams have worked really, really hard to get to this moment in time . . . this is what it is, really. The rules are there at the start. No one probably thought they would have to sort out result to some of that stuff. A great game of cricket and all you guys probably enjoyed it,” he added.

One of Williamson’s final comments was unmistakably poignant: “At the end of the day nothing separated us, no one lost the final, but there was a crowned winner and there it is.”

It is painful that this heart-stopping (literally so as Neesham’s coach died in New Zealand. His heart stopped in the Super over after Neesham had hit a six), most memorable, best-ever World Cup final should have had its outcome decided on such silliness. Would it not be embarrassing even for the Englishmen to tell their children that they had won the World Cup by zero runs!

What has been done cannot be undone. The stage cannot be re-set. Nor can the rules be revised with retrospective effect. The ICC should step forward and declare England and New Zealand as joint winners. This will be a worthy acknowledgement of Williamson’s truly venerable post-match gentlemanliness.

Short of this ICC verdict, the cricket historians will describe this World Cup as the most memorable, most exciting, most dramatic with the most insane, most tragic, most cruel ending.

– The writer is an ex-commentator

-

Emily Ratajkowski Appears To Confirm Romance With Dua Lipa's Ex Romain Gavras

Emily Ratajkowski Appears To Confirm Romance With Dua Lipa's Ex Romain Gavras -

Leighton Meester Breaks Silence On Viral Ariana Grande Interaction On Critics Choice Awards

Leighton Meester Breaks Silence On Viral Ariana Grande Interaction On Critics Choice Awards -

Heavy Snowfall Disrupts Operations At Germany's Largest Airport

Heavy Snowfall Disrupts Operations At Germany's Largest Airport -

Andrew Mountbatten Windsor Released Hours After Police Arrest

Andrew Mountbatten Windsor Released Hours After Police Arrest -

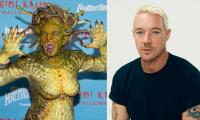

Heidi Klum Eyes Spooky Season Anthem With Diplo After Being Dubbed 'Queen Of Halloween'

Heidi Klum Eyes Spooky Season Anthem With Diplo After Being Dubbed 'Queen Of Halloween' -

King Charles Is In ‘unchartered Waters’ As Andrew Takes Family Down

King Charles Is In ‘unchartered Waters’ As Andrew Takes Family Down -

Why Prince Harry, Meghan 'immensely' Feel 'relieved' Amid Andrew's Arrest?

Why Prince Harry, Meghan 'immensely' Feel 'relieved' Amid Andrew's Arrest? -

Jennifer Aniston’s Boyfriend Jim Curtis Hints At Tensions At Home, Reveals Rules To Survive Fights

Jennifer Aniston’s Boyfriend Jim Curtis Hints At Tensions At Home, Reveals Rules To Survive Fights -

Shamed Andrew ‘dismissive’ Act Towards Royal Butler Exposed

Shamed Andrew ‘dismissive’ Act Towards Royal Butler Exposed -

Hailey Bieber Shares How She Protects Her Mental Health While Facing Endless Criticism

Hailey Bieber Shares How She Protects Her Mental Health While Facing Endless Criticism -

Amanda Seyfried Shares Hilarious Reaction To Discovering Second Job On 'Housemaid': 'Didn’t Sign Up For That'

Amanda Seyfried Shares Hilarious Reaction To Discovering Second Job On 'Housemaid': 'Didn’t Sign Up For That' -

Queen Elizabeth II Saw ‘qualities Of Future Queen’ In Kate Middleton

Queen Elizabeth II Saw ‘qualities Of Future Queen’ In Kate Middleton -

Hilary Duff Reveals Deep Fear About Matthew Koma Marriage

Hilary Duff Reveals Deep Fear About Matthew Koma Marriage -

Will Sarah Ferguson End Up In Police Questioning After Andrew’s Arrest? Barrister Answers

Will Sarah Ferguson End Up In Police Questioning After Andrew’s Arrest? Barrister Answers -

Matthew McConaughey Gets Candid About AI Threat To Actors: 'Be Prepared'

Matthew McConaughey Gets Candid About AI Threat To Actors: 'Be Prepared' -

Hailey Bieber Shares How 16-month-old Son Jack Blues Is Already Following In Justin Bieber's Footsteps

Hailey Bieber Shares How 16-month-old Son Jack Blues Is Already Following In Justin Bieber's Footsteps