Billion of Indians have no spending money: report

In fact, this has been a long-term structural trend that began even before pandemic

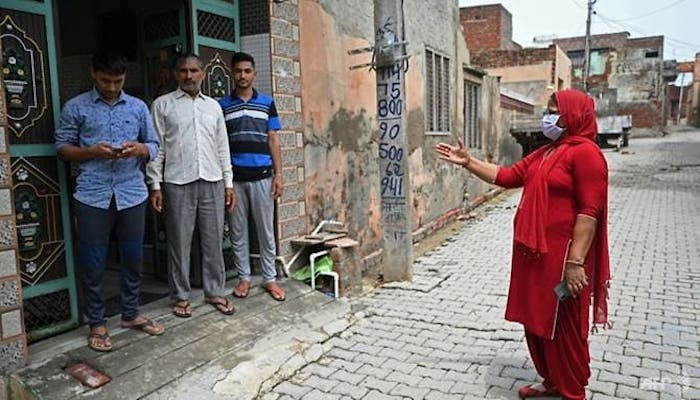

NEW DELHI: India is home to 1.4 billion people but around a billion lack money to spend on any discretionary goods or services, a new report estimates.

The country’s consuming class, effectively the potential market for start-ups or business owners, is only about as big as Mexico, 130-140 million people, according to the report from Blume Ventures, a venture capital firm.

Another 300 million are “emerging” or “aspirant” consumers but they are reluctant spenders who have only just begun to open their purse strings, as click-of-a-button digital payments make it easy to transact. What is more, the consuming class in Asia’s third largest economy is not “widening” as much as it is “deepening”, according to the report. That basically means India’s wealthy population is not really growing in numbers, even though those who are already rich are getting even wealthier.

All of this is shaping the country’s consumer market in distinct ways, particularly accelerating the trend of “premiumisation” where brands drive growth by doubling down on expensive, upgraded products catering to the wealthy, rather than focusing on mass-market offerings.

This is evident in zooming sales of ultra-luxury gated housing and premium phones, even as their lower-end variants struggle. Affordable homes now constitute just 18% of India’s overall market compared with 40% five years ago. Branded goods are also capturing a bigger share of the market. And the “experience economy” is booming, with expensive tickets for concerts by international artists like Coldplay and Ed Sheeran selling like hot cakes.

Companies that have adapted to these shifts have thrived, Sajith Pai, one of the report’s authors, told the BBC. “Those who are too focused at the mass end or have a product mix that doesn’t have exposure to the premium end have lost market share.”

The report’s findings bolster the long-held view that India’s post-pandemic recovery has been K-shaped -- where the rich have got richer, while the poor have lost purchasing power. In fact, this has been a long-term structural trend that began even before the pandemic. India has been getting increasingly more unequal, with the top 10 percent of Indians now holding 57.7 percent of national income compared with 34 percent in 1990. The bottom half have seen their share of national income fall from 22.2 percent to 15 percent.

India’s middle class -- which has been a major engine for consumer demand -- is being squeezed out, with wages pretty much staying flat, according to data compiled by Marcellus Investment Managers. “The middle 50 percent of India’s tax-paying population has seen its income stagnate in absolute terms over the past decade. This implies a halving of income in real terms [adjusted for inflation],” says the report, published in January.

“This financial hammering has decimated the middle class’s savings -- the RBI [Reserve Bank of India] has repeatedly highlighted that net financial savings of Indian households are approaching a 50-year low. This pounding suggests that products and services associated with middle-class household spending are likely to face a rough time in the years ahead,” it adds.

The Marcellus report also points out that white-collar urban jobs are becoming harder to come by as artificial intelligence automates clerical, secretarial and other routine work. “The number of supervisors employed in manufacturing units [as a percentage of all employed] in India has gone down significantly,” it adds. The government’s recent economic survey has flagged these concerns as well.

-

SpaceX Launches Another Batch Of Satellites From Cape Canaveral During Late-night Mission On Saturday

SpaceX Launches Another Batch Of Satellites From Cape Canaveral During Late-night Mission On Saturday -

Princess Beatrice, Eugenie Get Pulled Into Parents’ Epstein Row: ‘At Least Stop Clinging!’

Princess Beatrice, Eugenie Get Pulled Into Parents’ Epstein Row: ‘At Least Stop Clinging!’ -

Inside Kim Kardashian's Brain Aneurysm Diagnosis

Inside Kim Kardashian's Brain Aneurysm Diagnosis -

Farmers Turn Down Millions As AI Data Centres Target Rural Land

Farmers Turn Down Millions As AI Data Centres Target Rural Land -

Trump Announces A Rise In Global Tariffs To 15% In Response To Court Ruling, As Trade Tensions Intensify

Trump Announces A Rise In Global Tariffs To 15% In Response To Court Ruling, As Trade Tensions Intensify -

Chappell Roan Explains Fame's Effect On Mental Health: 'I Might Quit'

Chappell Roan Explains Fame's Effect On Mental Health: 'I Might Quit' -

AI Processes Medical Data Faster Than Human Teams, Research Finds

AI Processes Medical Data Faster Than Human Teams, Research Finds -

Sarah Ferguson’s Friend Exposes How She’s Been Since Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor’s Release

Sarah Ferguson’s Friend Exposes How She’s Been Since Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor’s Release -

Jelly Roll Explains Living With 'severe Depression'

Jelly Roll Explains Living With 'severe Depression' -

Charli XCX Applauds Dave Grohl’s 'abstract' Spin On Viral ‘Apple’ Dance

Charli XCX Applauds Dave Grohl’s 'abstract' Spin On Viral ‘Apple’ Dance -

Anna Sawai Opens Up On Portraying Yoko Ono In Beatles Film Series

Anna Sawai Opens Up On Portraying Yoko Ono In Beatles Film Series -

Eric Dane's Wife Rebecca Gayheart Shares Family Memories Of Late Actor After ALS Death

Eric Dane's Wife Rebecca Gayheart Shares Family Memories Of Late Actor After ALS Death -

Palace Wants To ‘draw A Line’ Under Andrew Issue: ‘Tried And Convicted’

Palace Wants To ‘draw A Line’ Under Andrew Issue: ‘Tried And Convicted’ -

Eric Dane's Girlfriend Janell Shirtcliff Pays Him Emotional Tribute After ALS Death

Eric Dane's Girlfriend Janell Shirtcliff Pays Him Emotional Tribute After ALS Death -

King Charles Faces ‘stuff Of The Nightmares’ Over Jarring Issue

King Charles Faces ‘stuff Of The Nightmares’ Over Jarring Issue -

Sarah Ferguson Has ‘no Remorse’ Over Jeffrey Epstein Friendship

Sarah Ferguson Has ‘no Remorse’ Over Jeffrey Epstein Friendship