Lyrid Meteor Shower 2024: When, where, how to see event?

Celestial event generates fireball meteors when it is at peak

Lyrid Meteor Shower, the magnificent climax of the sky show, which could see hundreds of shooting stars and "fireballs" flood the night sky, is expected to start later this week.

The Lyrids are among the oldest meteor showers known to history, having been detected by humans approximately 2,700 years ago, according to Nasa.

They are not quite as spectacular as the Perseids or some other meteor showers, but when the Lyrids are at their most active, they are known to generate fireball meteors, which are brilliant bursting space rocks, and meteor trains, which are continuous streaks of light that stay in the sky for several seconds.

The comet C/1861 G1 Thatcher, which completes one orbit of the Sun every 415.5 years, is the source of these meteor showers.

The comet burns up in our atmosphere once a year when Earth travels through its vast debris field, creating the illusion of shooting stars streaking across the night sky, according to Live Science.

The yearly occurrence typically spans two weeks in April, with a roughly day-long peak being the most noticeable.

The Lyrids started this year on April 15 and will run through April 29. They will, however, reach their peak on April 21 Sunday, and April 22 Monday.

When the moon is at its lowest on April 22, right before dawn, is the optimum time to see the Lyrids.

As long as there isn't too much cloud cover or light pollution around, people should still be able to view dozens of bright meteors at this point.

-

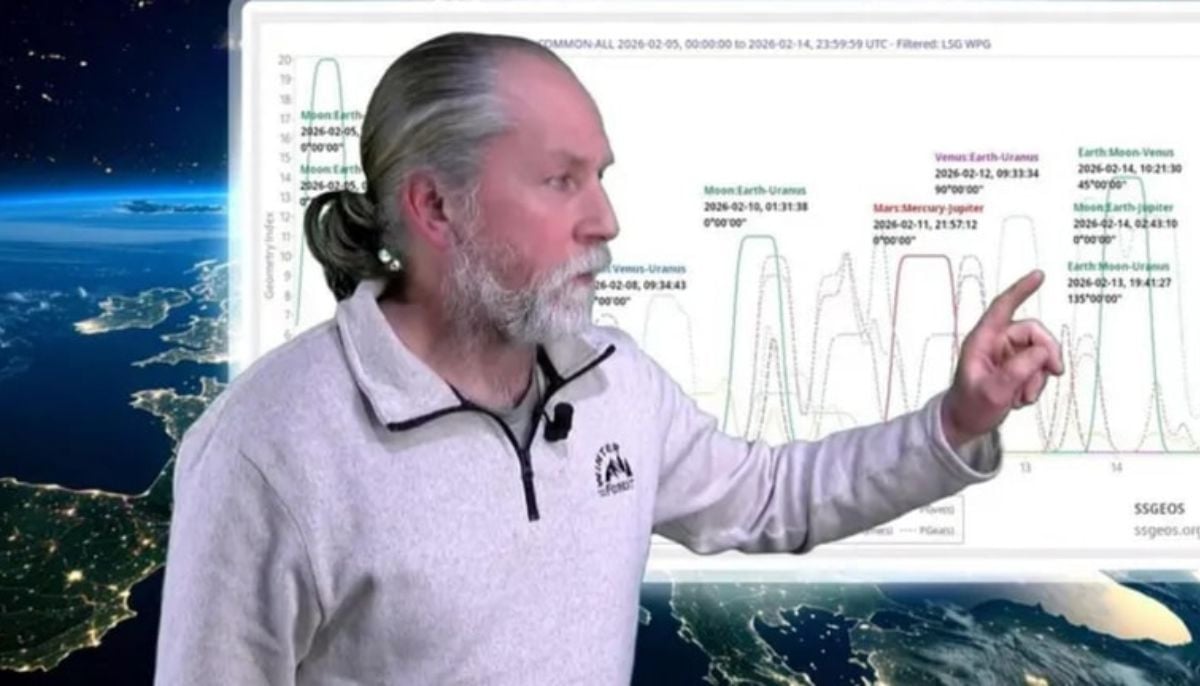

Dutch seismologist hints at 'surprise’ quake in coming days

-

SpaceX cleared for NASA Crew-12 launch after Falcon 9 review

-

Is dark matter real? New theory proposes it could be gravity behaving strangely

-

Shanghai Fusion ‘Artificial Sun’ achieves groundbreaking results with plasma control record

-

Polar vortex ‘exceptional’ disruption: Rare shift signals extreme February winter

-

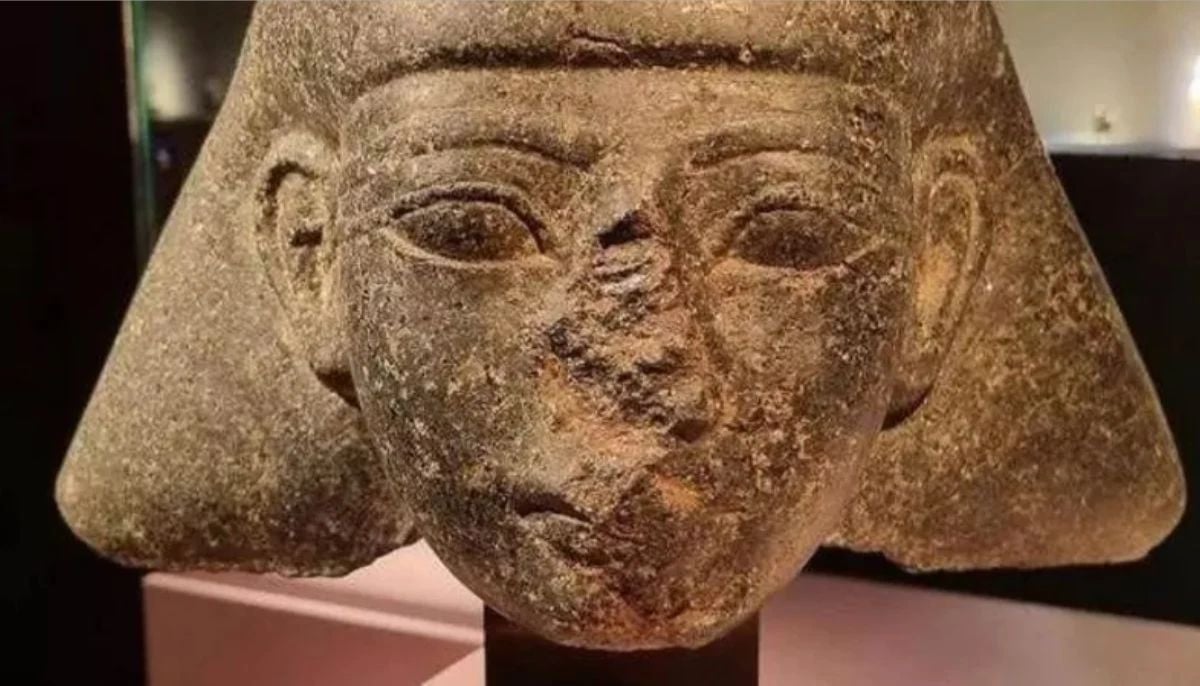

Netherlands repatriates 3500-year-old Egyptian sculpture looted during Arab Spring

-

Archaeologists recreate 3,500-year-old Egyptian perfumes for modern museums

-

Smartphones in orbit? NASA’s Crew-12 and Artemis II missions to use latest mobile tech