Do you know whales sing? New research shed light on whales' underwater melodies

Study focused on the voice boxes of three stranded whales — a humpback, minke, and sei — all belonging to the baleen whale family

In the vast expanse of the world's oceans, a mysterious symphony has been echoing for millions of years, captivating researchers and enthusiasts alike.

Whales, those majestic marine giants, have long been known for their hauntingly beautiful songs that traverse the deep blue. However, the mechanics behind these underwater melodies have remained an enigma—until now.

In a groundbreaking study published in the journal Nature, scientists have tried to unravel the secrets behind whales' vocalisations. The research, led by Coen Elemans of the University of Southern Denmark, studied the intricate world of baleen whales' voice boxes, or larynxes, shedding light on how these oceanic maestros produce their mesmerising tunes.

The study focused on the voice boxes of three stranded whales — a humpback, minke, and sei — all belonging to the baleen whale family.

Elemans and his team conducted controlled experiments, blowing air through the whale voice boxes to understand the vibrations of different tissues. Additionally, they created computer models to simulate the sei whale's vocalisations, comparing them to recordings from similar whales in the wild.

Whales, whose ancestors once roamed the land around 50 million years ago, have undergone a remarkable evolutionary journey to adapt their voice boxes for underwater communication.

Unlike humans and other mammals, baleen whales lack teeth and vocal cords. Instead, they possess a unique U-shaped tissue allowing them to inhale massive amounts of air. This, combined with a substantial "cushion" of fat and muscle, forms the basis of their musical skill underwater.

"This is the most comprehensive and significant study to date on how baleen whales vocalise, a long-standing mystery in the field," remarks Jeremy Goldbogen, an associate professor of oceans at Stanford University, who was not involved in the research.

However, as the oceanic melodies face a potential threat, concerns arise. Shipping industry noise, louder than even the powerful songs of humpbacks, poses a challenge to these majestic creatures.

Michael Noad, director of the Centre for Marine Science at the University of Queensland, warns that dispersed whale populations may struggle to find mates in a noisy ocean environment.

The study, while a crucial step forward, leaves room for further exploration. Joy Reidenberg, a whale expert from the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, emphasises the need for experiments on adult males, the primary singers among whales.

"Right now, our technology involves sticking a scope into a whale to see what exactly is vibrating," she notes. "Since you're never going to be able to do that in a wild animal, these experiments are the next best thing."

As the scientific community tunes into the melody of whale communication, the newfound insights pave the way for a deeper understanding of these oceanic ballads and the challenges they face in a changing marine environment.

-

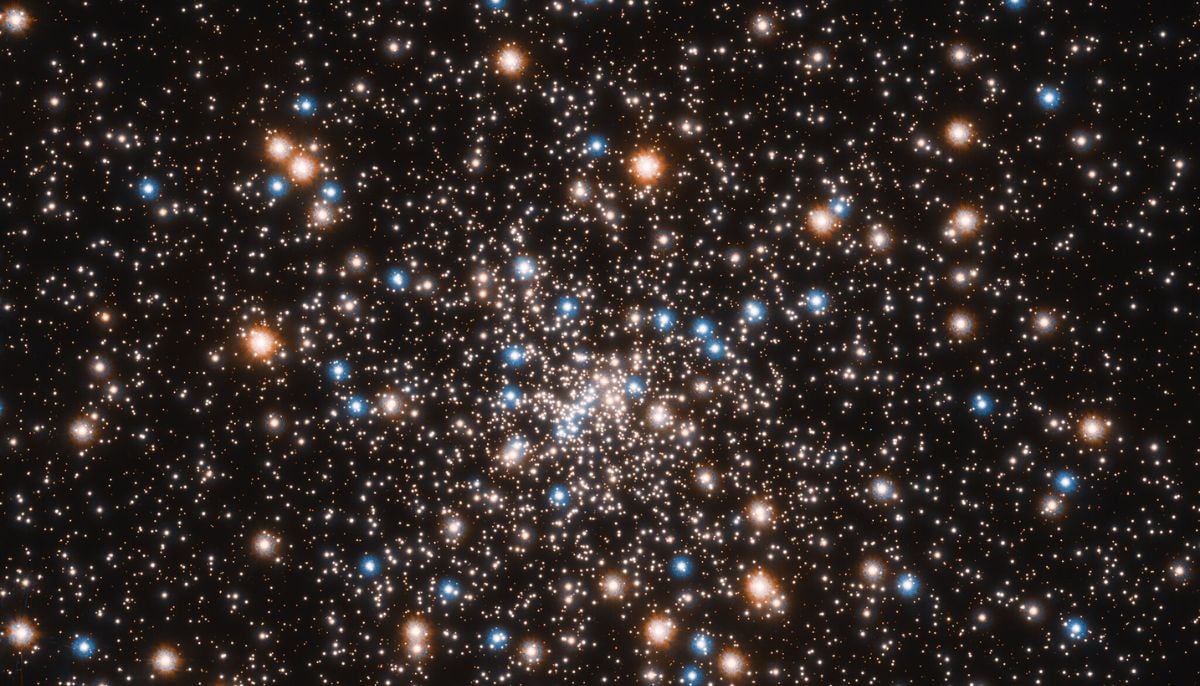

Hidden ‘dark galaxy' traced by ancient star clusters could rewrite the cosmic galaxy count

-

Astronauts face life threatening risk on Boeing Starliner, NASA says

-

Giant tortoise reintroduced to island after almost 200 years

-

Blood Falls in Antarctica? What causes the mysterious red waterfall hidden in ice

-

Scientists uncover surprising link between 2.7 million-year-old climate tipping point & human evolution

-

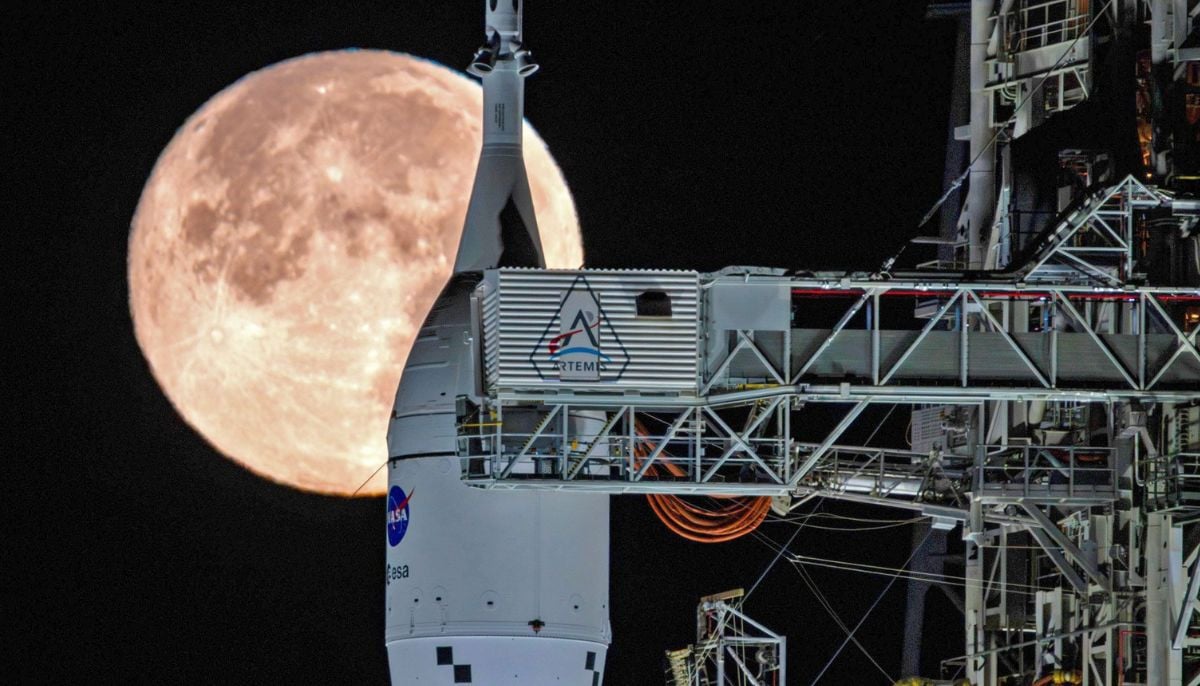

NASA takes next step towards Moon mission as Artemis II moves to launch pad operations following successful fuel test

-

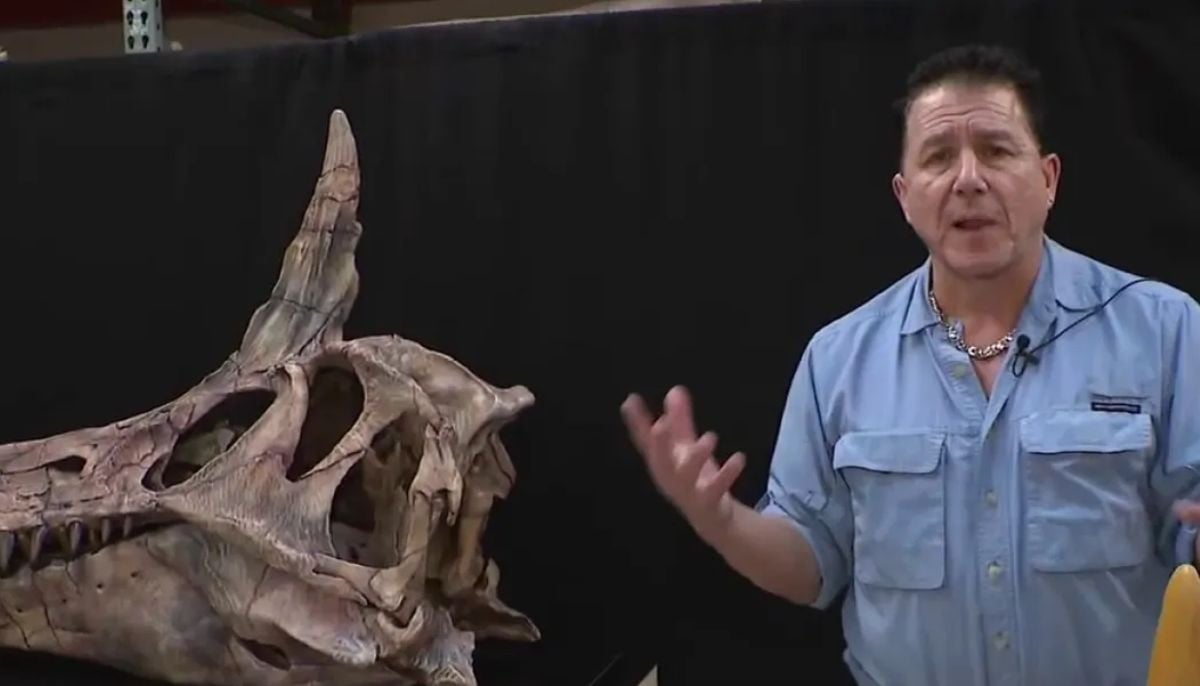

Spinosaurus mirabilis: New species ready to take center stage at Chicago Children’s Museum in surprising discovery

-

Climate change vs Nature: Is world near a potential ecological tipping point?