California removing four dams along Klamath River to restore nature and combat climate change

By this time next year, imposing dams along Klamath River, originally constructed in the 1950s, will cease to exist

California is currently spearheading the world's most extensive dam removal project, with the goal to address the challenges posed by climate change.

The project primarily focuses on reviving the Klamath River by dismantling a series of massive dams that have impeded its flow for decades.

By this time next year, these imposing dams, originally constructed in the 1950s, will cease to exist. The soil and rocks, initially excavated from a nearby mountain, will be returned to their natural surroundings, allowing the river to flow freely once more.

The Iron Gate Dam, the final installation among four towering dams, which regulated the river's flow and water supply for Northern California, now stands as the epicentre of this monumental dam removal and river restoration initiative.

The removal process for one of these dams, Copco2, was notably swift, taking only a few months, in stark contrast to the nearly decade-long construction of the Iron Gate Dam.

Mark Bransom, CEO of the Klamath River Renewal Corporation, affirmed that the river's course will be unimpeded once the dam's infrastructure is dismantled. The restoration plans include the use of native vegetation to stabilise the remaining sediments once the reservoir is drained.

In light of extreme heat, record droughts, and catastrophic floods linked to climate change, a nationwide "rewilding" movement seeks to restore nature to its pre-human intervention state, with the aim of mitigating climate change's effects. Dams, many originally constructed without environmental considerations, have become a focal point of this effort.

"One of the fastest ways to heal a river is to remove a dam," stated Ann Willis, California regional director for American Rivers, a water-focused nonprofit organisation. Willis emphasised that rivers can begin to restore themselves once the water flows freely.

The US Army Corps of Engineers, responsible for maintaining the National Inventory of Dams, has identified 76% of existing U.S. dams as having "high hazard potential." The Iron Gate Dam, for instance, features toxic algae in its stagnant reservoir, posing a threat to water quality and safety.

Tribal activists have played a pivotal role in advocating for the dam's decommissioning, highlighting the near extinction of salmon in the Klamath River, which has disrupted sacred practices of the Karuk, Yurok, and Hoopa tribes.

The ambitious project carries a price tag of $500 million, funded by taxpayers and PacifiCorps, the local electric power company. While some homeowners have expressed concerns about declining property values, proponents argue that the cost is justified to restore nature and point to the success of the Elwha Dam Removal project in Washington state.

Looking ahead, advocates hope to replicate the Klamath River's restoration success in other regions, such as the current federal proposal to breach four dams on the lower Snake River in eastern Washington, with an estimated cost of $33.5 billion.

-

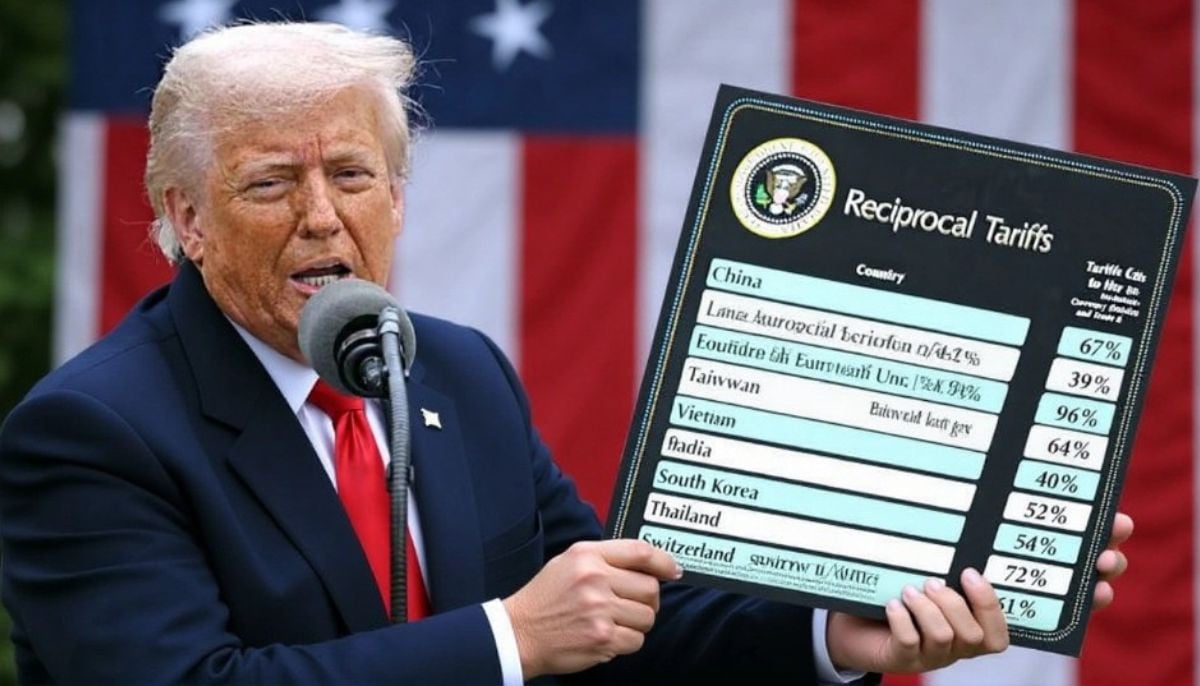

Trump announces new 10% global tariff after Supreme Court setback

-

Tucker Carlson says passport seized, staff member questioned at Israel airport

-

Russia set to block overseas crypto exchanges in sweeping crackdown

-

US Supreme Court strikes down Trump’s global tariffs as 'unlawful'

-

Kelly Clarkson explains decision to quit 'The Kelly Clarkson Show'

-

Japan: PM Takaichi flags China ‘Coercion,’ pledges defence security overhaul

-

Angorie Rice spills the beans on major details from season 2 of ' The Last Thing He Told Me'

-

Teacher arrested after confessing to cocaine use during classes