Is this the end of the old order?

Xi signed several cooperation agreements with Malaysia focused on trade, services, industrial parks and agriculture

On April 16, 2025, the World Trade Organization (WTO) issued a significant warning regarding the escalating trade tensions between the US and China, stating that these developments could have "severe negative consequences" for the global economy.

The WTO revised its projections for global trade growth, indicating a shift from an anticipated increase of 2.7 per cent to a decline of 0.2 per cent this year, primarily due to the intensifying tariff conflict initiated by US President Donald Trump. The organisation also warns that should the highest tariffs be reinstated, global trade may contract by as much as 1.5 per cent, which could potentially reduce global GDP growth to merely 1.7 per cent.

The latest tariffs include a comprehensive 10 per cent levy on all Chinese imports and an exceptionally high 145 per cent tariff on specific Chinese goods, with the possibility of escalating to 245 per cent in certain sectors. The US administration has justified these measures as necessary responses to China’s alleged involvement in the fentanyl supply chain and purported unfair trade practices.

In retaliation, China has imposed tariffs between 10 and 15 per cent on various US products, including coal, liquefied natural gas, crude oil, agricultural machinery and vehicles. It is anticipated that bilateral trade between the US and China could decrease by as much as 91 per cent if exemptions for technology products are not established, resulting in a significant decoupling of the two largest economies and the disruption of global supply chains. This decoupling is expected to lead to the emergence of two distinct global trade blocs, which would carry substantial implications for international commerce and economic stability.

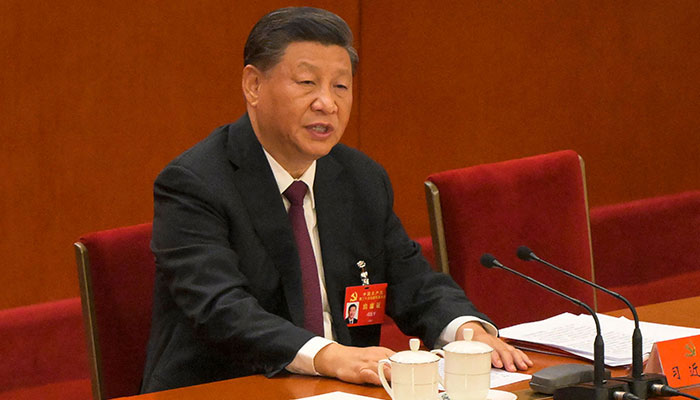

In the context of these tensions, Chinese President Xi Jinping has initiated a diplomatic tour of Southeast Asia, encompassing Malaysia, Vietnam and Cambodia, to strengthen regional alliances and counter the repercussions of U.S. protectionism. In Kuala Lumpur, President Xi articulated China's commitment to collaborating with Southeast Asian nations in resisting unilateralism and advancing regional development. He proposed an expedited free trade agreement between China and Asean and signed several cooperation agreements with Malaysia focused on trade, services, industrial parks and agriculture.

The US is experiencing a significant decline in its influence not only in Asia but also across Africa. In a notable development, Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni has implemented a ban on the export of iron ore and other unprocessed raw materials to the US and other Western nations. This decision, framed as an initiative to promote national industrialisation and value addition, directly confronts the longstanding neocolonial dynamics that have defined Africa’s role as a supplier of raw materials to Western economies. President Museveni stated, “We are not going to be hewers of wood and drawers of water anymore. The time has come for Africans to build, process, and export finished products, not merely to serve Western industries with our resources.”

This ban has already ignited broader discussions across the continent regarding self-sufficiency and post-colonial economic independence. Nations such as the Democratic Republic of Congo and Zambia, which possess significant reserves of copper and cobalt, are reportedly contemplating similar policies, suggesting a potential continental shift in economic strategies. Such a realignment could have serious repercussions for the US and Europe, which rely on African minerals for their transitions to green energy and their high-tech sectors.

The evolving geopolitical landscape indicates a fragmentation of the global trading system, characterised by the emergence of two competing economic blocs, one centred around the US and its traditional allies, and another increasingly led by China and a coalition of developing economies. Analysts project that, should current trends persist, nations will be compelled to align themselves more definitively with one bloc or the other, potentially resulting in a Balkanised global economy.

Developing countries are already recalibrating their strategies; nations across Southeast Asia, Latin America and Africa are investigating new trade corridors, including the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), BRICS+ platforms, and independent bilateral free trade agreements that are not reliant on US or EU frameworks. Amid this instability, there are clear opportunities for developing economies.

For Pakistan, the evolving dynamics of global trade present both a diplomatic challenge and a strategic opportunity. On the one hand, Pakistan has strengthened its economic and infrastructural connections with China through the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a flagship initiative within Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). As China confronts increasing tariffs imposed by the US, Pakistan has the potential to emerge as a vital manufacturing and logistics partner, facilitating access for Chinese goods to markets in the Middle East, Central Asia and Africa.

Conversely, Pakistan must also navigate its longstanding, albeit complex, relationship with the US, which remains a crucial participant in financial assistance, defence collaboration and international diplomacy. Rather than adopting a binary stance, Islamabad can pursue a policy of ‘strategic balancing’, positioning itself as a neutral conduit for dialogue, a trade hub for East-West commerce and a diplomatic ally in regional peace initiatives.

Through bilateral cooperation with both powers, anchored in transparency, mutual respect and economic practicality, Pakistan could elevate its status from a peripheral participant to a central stakeholder in the evolving multipolar trade landscape. However, to fully capitalise on these opportunities, Pakistan needs to undertake significant reforms in governance, investment policy, trade facilitation and digital infrastructure. Such reforms are essential to ensure potential partners of its reliability and operational capacity.

The vacuum resulting from declining US-China trade flows offers developing nations the chance to enhance their exports, attract relocated manufacturing operations, and strengthen South-South cooperation. Countries such as Vietnam, Indonesia, Brazil and Kenya are witnessing increased foreign direct investment as companies seek alternative production sites to evade punitive tariffs. For instance, Indonesia recently finalised a $4 billion lithium processing agreement with South Korea, while Mexico’s industrial zones are becoming increasingly populated with firms relocating from China.

To capitalise on these opportunities, developing nations must adeptly navigate the intricate geopolitical landscape and enhance their institutional, infrastructural and legal frameworks. Improvements in logistics, digital infrastructure, and customs modernisation will be critical for their integration into diversified global value chains. Aligning national trade policies with sustainability objectives and human rights standards can also confer a competitive advantage in a marketplace progressively influenced by environmental, social and governance (ESG) compliance.

In light of recent developments, the WTO has urged caution, warning that the ‘weaponisation of trade’ could result in systemic harm that extends beyond the immediate parties involved. WTO Director-General Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala has called upon all nations to resolve their differences through dialogue rather than coercion, emphasising that the global economy cannot withstand prolonged uncertainty. She has also highlighted the necessity of shielding developing nations from collateral damage, as they are particularly vulnerable to supply shocks, capital flight and investment volatility.

The US-China tariff conflict has disrupted the global trade system but is also simultaneously reshaping it in ways that may favour emerging economies, provided they respond decisively. With the US relinquishing influence not only in Asia but also in Africa, the traditional world order is becoming increasingly tenuous. Countries such as Uganda are asserting their economic sovereignty and resisting exploitative trade practices, marking a pivotal shift in global politics.

Concurrently, nations across the Global South are forming new coalitions, revising trade agreements and asserting their claims for representation. What develops during this turbulent period may not signify the end of globalisation, but rather the next chapter – one that is more decentralised, contested and inclusive than ever before.

The writer is a trade facilitation expert, working with the federal government of Pakistan.

-

Prince William, Kate Middleton Camp Reacts To Meghan's Friend Remarks On Harry 'secret Olive Branch'

Prince William, Kate Middleton Camp Reacts To Meghan's Friend Remarks On Harry 'secret Olive Branch' -

Daniel Radcliffe Opens Up About 'The Wizard Of Oz' Offer

Daniel Radcliffe Opens Up About 'The Wizard Of Oz' Offer -

Channing Tatum Reacts To UK's Action Against Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor

Channing Tatum Reacts To UK's Action Against Andrew Mountbatten-Windsor -

Brooke Candy Announces Divorce From Kyle England After Seven Years Of Marriage

Brooke Candy Announces Divorce From Kyle England After Seven Years Of Marriage -

Piers Morgan Makes Meaningful Plea To King Charles After Andrew Arrest

Piers Morgan Makes Meaningful Plea To King Charles After Andrew Arrest -

Sir Elton John Details Struggle With Loss Of Vision: 'I Can't See'

Sir Elton John Details Struggle With Loss Of Vision: 'I Can't See' -

Epstein Estate To Pay $35M To Victims In Major Class Action Settlement

Epstein Estate To Pay $35M To Victims In Major Class Action Settlement -

Virginia Giuffre’s Brother Speaks Directly To King Charles In An Emotional Message About Andrew

Virginia Giuffre’s Brother Speaks Directly To King Charles In An Emotional Message About Andrew -

Reddit Tests AI-powered Shopping Results In Search

Reddit Tests AI-powered Shopping Results In Search -

Winter Olympics 2026: Everything To Know About The USA Vs Slovakia Men’s Hockey Game Today

Winter Olympics 2026: Everything To Know About The USA Vs Slovakia Men’s Hockey Game Today -

'Euphoria' Star Eric Made Deliberate Decision To Go Public With His ALS Diagnosis: 'Life Isn't About Me Anymore'

'Euphoria' Star Eric Made Deliberate Decision To Go Public With His ALS Diagnosis: 'Life Isn't About Me Anymore' -

Toy Story 5 Trailer Out: Woody And Buzz Faces Digital Age

Toy Story 5 Trailer Out: Woody And Buzz Faces Digital Age -

Andrew’s Predicament Grows As Royal Lodge Lands In The Middle Of The Epstein Investigation

Andrew’s Predicament Grows As Royal Lodge Lands In The Middle Of The Epstein Investigation -

Rebecca Gayheart Unveils What Actually Happened When Ex-husband Eric Dane Called Her To Reveal His ALS Diagnosis

Rebecca Gayheart Unveils What Actually Happened When Ex-husband Eric Dane Called Her To Reveal His ALS Diagnosis -

What We Know About Chris Cornell's Final Hours

What We Know About Chris Cornell's Final Hours -

Scientists Uncover Surprising Link Between 2.7 Million-year-old Climate Tipping Point & Human Evolution

Scientists Uncover Surprising Link Between 2.7 Million-year-old Climate Tipping Point & Human Evolution