‘History proves them right’: Three decades on, Swiss women strike again for equality

Every night for more than 600 years, a night watchman has climbed to the top of Lausanne Cathedral’s bell tower to bellow out the hour, preserving a centuries-old tradition cherished by many in the picturesque city on the shores of Lake Geneva.

Twenty-eight years after staging a historic walkout, women from across Switzerland will again take to the streets this Friday for a nationwide strike aimed at highlighting the country's poor record on gender equality.

Every night for more than 600 years, a night watchman has climbed to the top of Lausanne Cathedral’s bell tower to bellow out the hour, preserving a centuries-old tradition cherished by many in the picturesque city on the shores of Lake Geneva.

But on the stroke of midnight on Thursday, the watchman of Lausanne will give way to the city’s very first watchwoman – four of them, in fact. In a variation on an age-old theme, they are expected to call out, “This is the watchwoman. The bell has tolled twelve. The bell has tolled the start of the strike.”

The bell tower ritual in Lausanne will kick off a 24-hour women’s strike across this prosperous Alpine nation steeped in tradition and regional identity, which has long lagged other developed economies when it comes to women’s rights.

“This is still a very conservative and unequal country,” says Vanessa Monney, a Lausanne-based trade unionist and one of the organisers of Friday’s strike. She adds: “Can you believe women in Switzerland had to wait until the 1970s to be able to cast a vote?”

Europe’s laggard

In one of its least distinguished records, Switzerland only granted women the right to vote in 1971, a move opposed by (male) voters in eight of the country’s 26 cantons. It would take another two decades for deeply conservative Appenzell Innerrhoden to finally allow women to vote in cantonal elections – and only because the federal Supreme Court forced it to.

In theory, gender equality was enshrined in the constitution in 1981. But persistently stark inequality prompted half a million women – a quarter of Switzerland’s female population at the time – to stage a historic strike on June 14, 1991. Women blocked traffic and gathered outside schools, hospitals and across cities with purple balloons and banners to demand equal pay for equal work.

The success of the strike led to the approval of a Gender Equality Act five years later. That law banned workplace discrimination and sexual harassment, and protected women from bias or dismissal over pregnancy, marital status, or gender. But more than 20 years later, women still face lower pay than men, routine questioning of their competence, and condescension and paternalism on the job.

“It’s been 38 years since gender equality was written into the constitution, and yet this equality still hasn’t materialised,” says Monney. “In fact we’ve seen an increase in the gender pay gap in recent years.”

Work unpaid

Swiss women earn roughly 20 percent less than men. While that is down from about a third in 1991, the discrimination gap – meaning differences that cannot be justified by rank or role – has actually worsened since 2000, according to data compiled by the Federal Statistics Office. Women’s rights activists were frustrated last year when parliament watered down plans to introduce regular pay equity checks, limiting them to companies with over 100 employees.

Wage discrepancies for men and women performing the same tasks are not the only problem, says Monney. An enduring division of labour means women still tend to end up in lower paid professions, often juggling part-time work with unpaid childcare and household chores.

“There is a critical lack of state-funded childcare provision in Switzerland and still no paternity leave,” she explains. “As a result, women face conflicting injunctions. They are increasingly present on the job market, but confined to low-paid, part-time jobs that require ever greater flexibility, and this clashes with their family workload.”

Organisers say Friday’s strike is aimed at highlighting the wage gap, recognising the care work women carry out, the violence they still suffer, and the need for greater representation in positions of power and for more equitable family policy. In schools, teachers and caregivers will strike for better pay in female-dominated roles and for better work-family balance, asking fathers to pick children up early and leaving other children in the care of male peers.

"We're striking because women earn less for the same work, are passed over for promotions, are hardly represented at the executive level and because typically female jobs are poorly paid," co-organisers the Women*strike Collective Zurich wrote in a manifesto. The collective said its temporary office has been flooded with visitors and hundreds of people, including men, have sent emails expressing solidarity and asking about how they can participate.

Breaking taboos

In the French-speaking Vaud canton, Monney says she and her fellow strikers have been emboldened by the March 8 strikes staged by women in Spain and Belgium, and the recent school strikes for climate staged by students around the world. She argues that the two movements share a common critique of the exploitative nature of capitalism.

The trade unionist acknowledges that going on strike is a sensitive – or even “taboo” – subject in Switzerland, where industrial relations have long been based on a culture of compromise. While this may have alienated some conservative women, who otherwise share many of the strikers’ concerns, Monney is confident the June 14 strike will attract an even higher turnout than the mass movement of 1991.

Feminism has long been another taboo word in Switzerland, says Anne Rothenbüler, a Research Associate at Paris Ouest University, who specialises in the history of women and immigration. “In my youth it was an insult, it meant you weren’t looking after your children,” she explains.

Rothenbüler credits the global #MeToo movement with inspiring Swiss youths to challenge the patriarchal culture that has long permeated many Swiss cantons, particularly the Catholic ones. “This culture is still reflected in everyday life,” she says. “You see it in the fact that most schools don’t have a canteen, because ‘mother does the cooking’, or in antiquated laws on sexual assault, which still limit rape to forceful vaginal penetration by a penis.”

Uniting the veterans of the 1991 movement with a new generation of campaigners, including climate and LGBT activists, may be one of the greatest achievements of Friday's strike. In an editorial published on Wednesday, French-speaking daily Le Temps hailed the “solidarity” and “fertile intergenerational mingling” fostered by the June 14 gathering.

“History proves women right: we owe the Gender Equality Act to the extraordinary mobilization of 1991,” the paper wrote. “It will take another strike to end the politics of small steps – steps that are too small to […] topple a patriarchal system.”

-

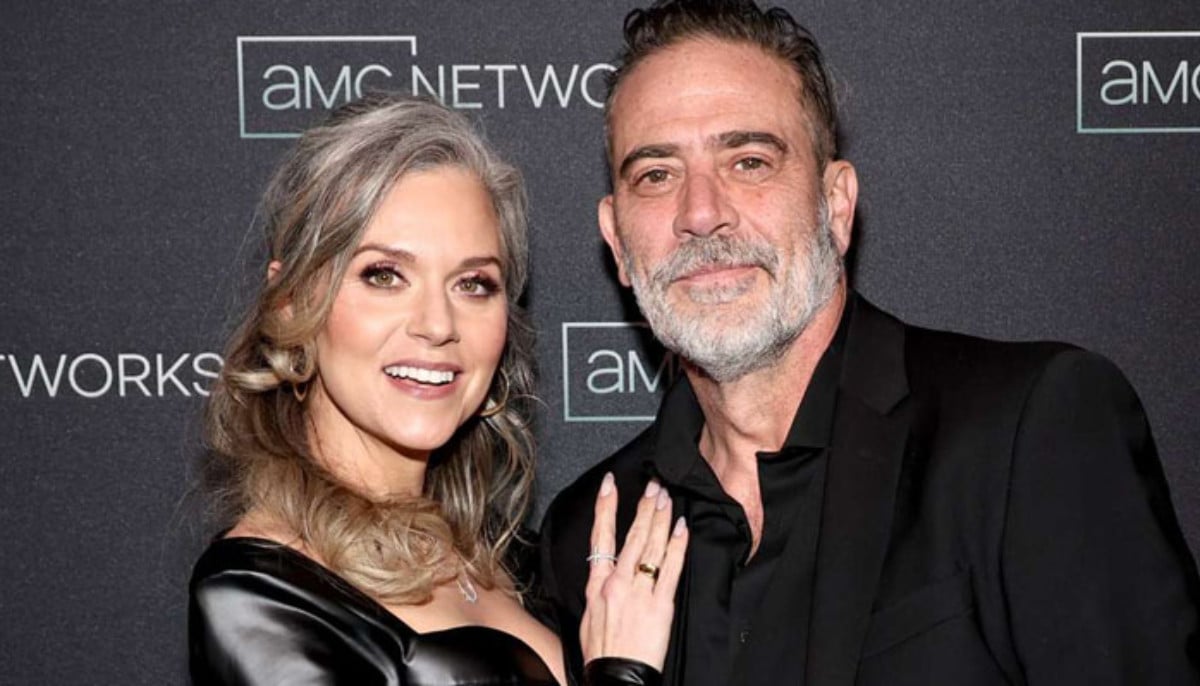

Hilarie Burton reveals Valentine's Day plans with Jeffrey Dean Morgan

-

Jacob Elordi, Margot Robbie on 'devastating' scene in 'Wuthering Heights'

-

China to implement zero tariffs on African imports in major trade shift

-

Jack Thorne explains hidden similarities between 'Lord of the Flies' and 'Adolescence'

-

Elon Musk vs Reid Hoffman: Epstein files fuel public spat between tech billionaires

-

New Zealand flood crisis: State of emergency declared as North Island braces for more storms

-

Nancy Guthrie case: Mystery deepens as unknown DNA found at property

-

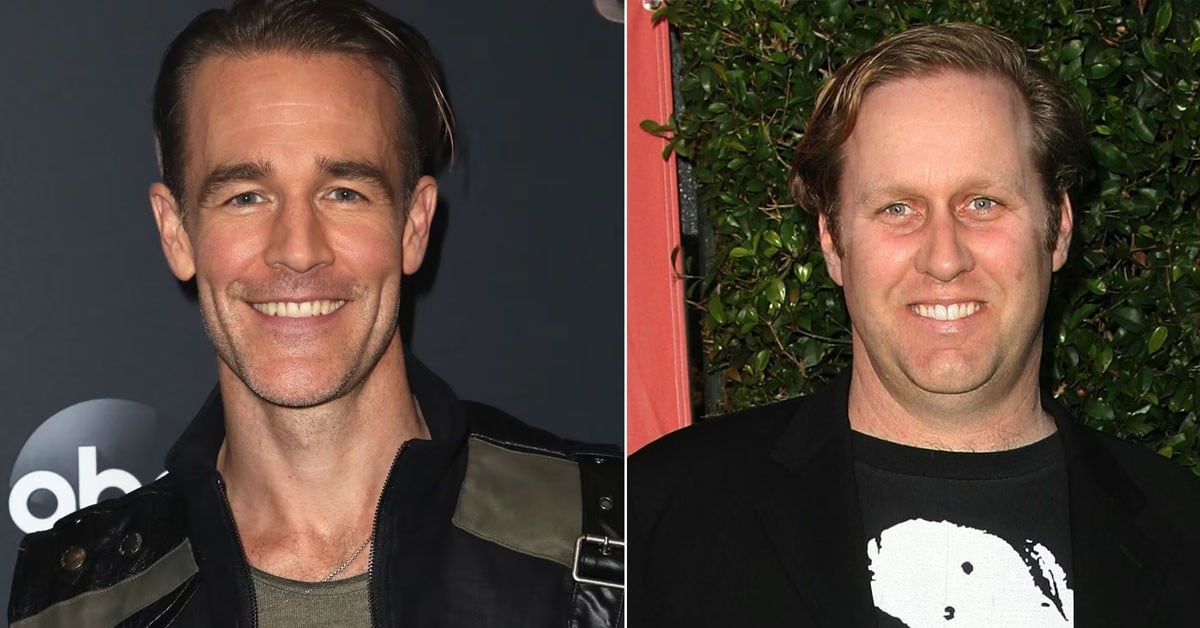

James Van Der Beek's final conversation with director Roger Avary laid bare: 'We cried'