Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto's grandson showcases portraits of life and death in distinct art exhibition

Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto is a visual artist, performer and curator. The artist is son of late Murtaza Bhutto and grandson of the former Prime Minister of Pakistan, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto.

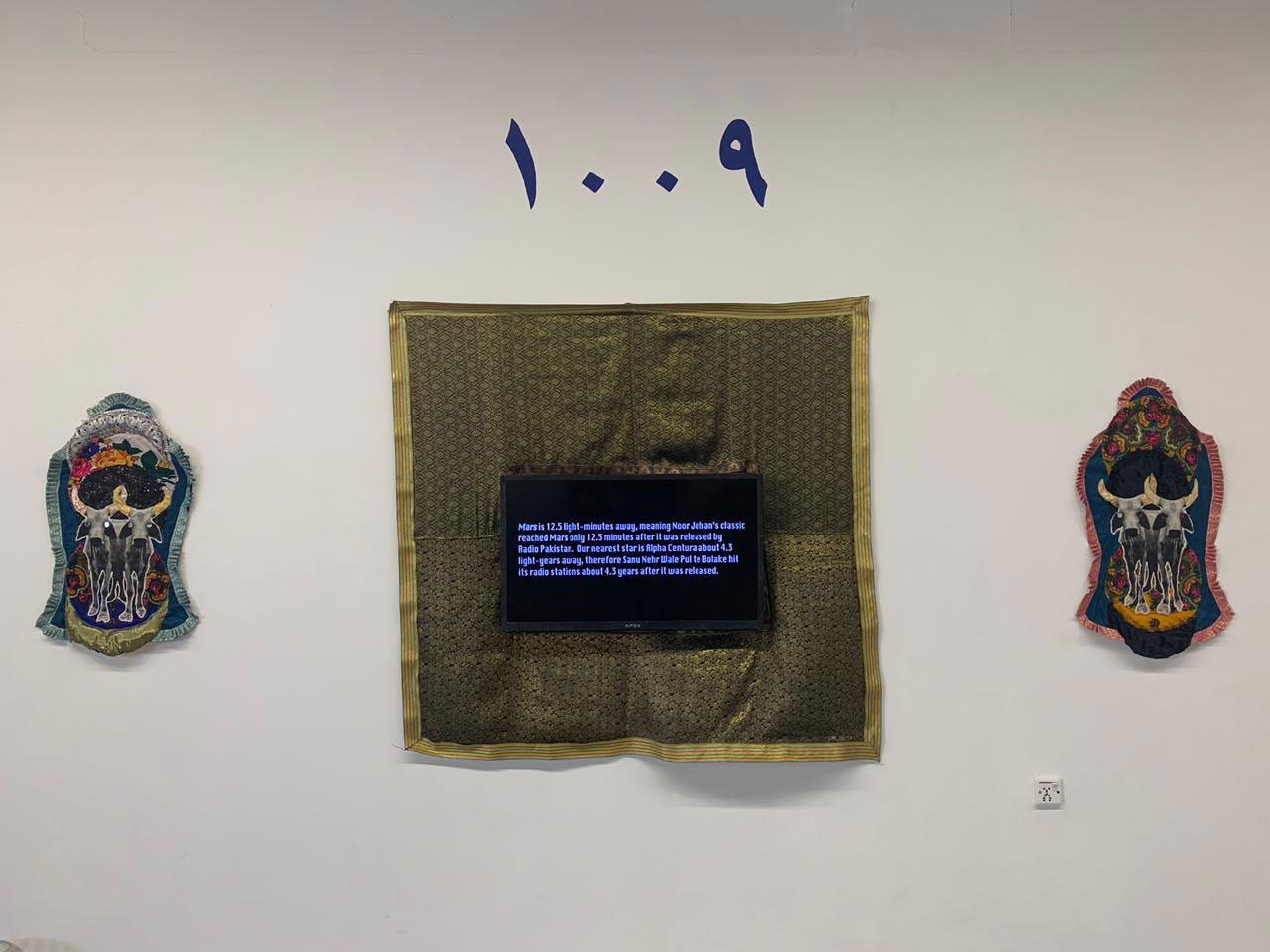

Multifaceted instalation, and the first to unite Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto’s performance, video, and textile-based practices in a solo show titled ‘Tomorrow We Inherit the Earth: Notes from a Guerrilla War’ was showcased at the Sanat Gallery, Karachi.

Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto is a visual artist, performer and curator. The artist is son of late Murtaza Bhutto and grandson of the former Prime Minister of Pakistan, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto. Bhutto’s work explores complex histories of colonialism that are exacerbated by contemporary international politics and in the process unpacks the intersections of queerness and Islam through a multi-media practice. He has shown in galleries, museums and theaters globally, as well as spoken extensively on the intersections of faith, radical thought and futurity at world renowned institutions like Columbia University, UC Berkeley, The California College of the Arts and Mills College.

Bhutto is currently based in California where he received a degree of Masters in Fine Arts at the San Francisco Art Institute in 2016.

The current series consists of artworks based on experimenting with diverse and overlapping aesthetics of textile, collage, mapping and archival materials to create rich layered and complex pieces that resonate and aesthetically delve into the world that the artist makes visible for the viewer.

The exhibition addresses the anxieties around fascism and oppression of our current times to imagine better possible future. The resultant body of work is an explosive and colourful homage to what is possible. Insurgents and fighters are queered to become aesthetic subjects, their bombs and guns releasing bouquets of flowers.

Bhutto talked about those whose lives were violently cut short because their skin colour, faith or ethnicity, their sexual or gender identity do not bend to prohibitive western norms will live again.

One can see tapestries laden with text and images of the weapons of war - hand grenades, bazookas, and gas masks - that will be used by the undead in his artworks. Single words or phrases hover in isolation, perhaps as a meditative aid or a directive for the ones who will also rise and fight.

An artwork showed sequin handmade objects that are supposed to be highly skilled yet low paid artisan work. By creating a craft generally associated with women and finishing each object with feminine embellishment, Bhutto addresses masculinity and militarism.

In this series, Islam is used as vehicle to propel the futurist imagination, looking into its occult practices, mysticism and the evolution of its politicization. It is important to note that since the independence of much of South Asia and the Arab world from the British and the French, resistance movements - in particular against the continued Western intervention through the Cold War have been overall secular, bringing people together from all religious communities. Islam, however still remained important as a unifying entity and an ideology that in some cases replaced the binary that historically existed between communism and capitalism.

The process behind the series is threefold: employing textile based installations, video works and performance. Tapestries are created to honour real and imagined queer guerrilla fighters and the weapons they used, following from traditions of martyr and saint veneration. The source imagery for these male figures are Pakistani wrestlers whose bodies are bejeweled and morphed into more opulent images of what a fighter might look like in a queer world.

Each installation was mapped out and inspired by numerous diagrams constructed by 13th century mystic Al-Buni and maps of the cosmos created by 13th century Muslim occultist, Ibn Arabi.

He utilized animation and archival footage to build a narrative around a fictitious revolution the world has not yet seen while my performances serve to interact with his videos. ‘My performance character Faluda Islam represents quite literally the living martyr, a drag queen turned rebel fighter killed in an encounter who is then resurrected as a zombie to continue battle. In this way, the very notion of the hero is questioned and intentionally subverted. This trajectory is inspired by Sarah Juliet Lauro and Karen Embry’s Zombie Manifesto whereby the figure of the zombie represents the fear of the unstoppable masses and destroys all boundaries, including those between life and death. Marginalized histories of resistance, including the involvement of women in Lebanon’s civil war and the gay Algerian rebel prisoner’s in Jean Genet’s Un Chant d’Amour are resurrected, resulting in the free flowing exchange between ghost, zombie, monster and human.’

Thus creative and having political context Bhutto’s work reflected post colonial, post Arab Spring, diasporic, queer moments whose direct inspiration and concepts came from different past incidents that left sharp memories in the minds of people who observed them or went through them.

-

Rare Gauguin fetches 9.5 mn euros at Paris auction

-

Vibrant compositions

-

Artist Mashkoor Raza's bold and soft compositions

-

Sanki King brings a burst of energy in graffiti

-

Remembering the forgotten

-

‘Being Edhi’ – means to serve humanity

-

New technique reveals lost splendours of Herculaneum art

-

Louvre offers virtual ´tete-a-tete´ with the Mona Lisa