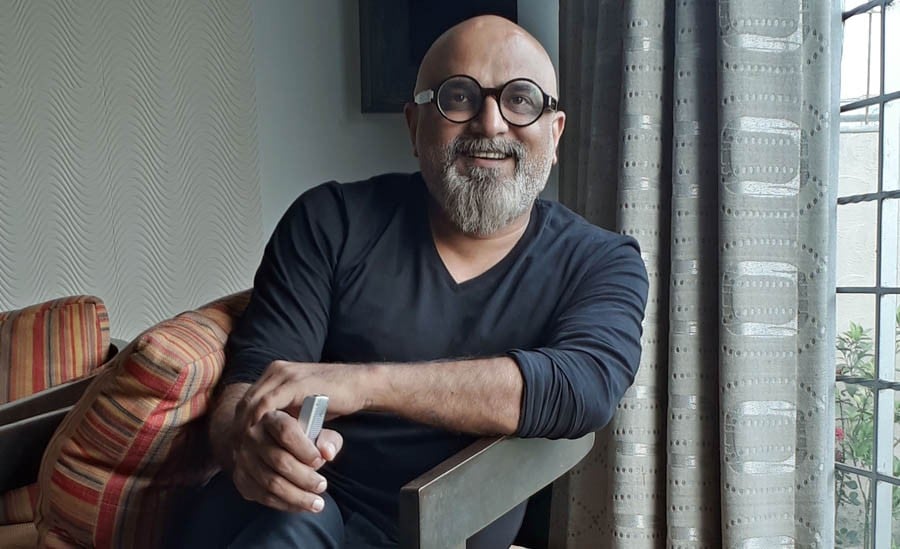

An exclusive chat with new media artist Faisal Anwar

Canadian-based Pakistani new media artist Faisal Anwar’s love for finding connections among people beyond geographical and cultural boundaries, coupled with a fascination for different mediums of communication, chiefly video, has taken him places -- literally. This Graphic Design graduate from National College of Arts, Lahore, had to travel across Pakistan at an early age, as his father was a veterinarian in public sector. Later, prospects of higher education and lack of interesting job opportunities on home front led him to Canada where he attended a post-grad certificate course in Interactive Art and Entertainment Program at the Canadian Film Center, before taking up prestigious artist residencies at the Banff New Media Institute, the University of Toronto Mississauga and, more recently, at Parramatta Artist Studios in Sydney, Australia.

Presently, he is running his own studio, Digital Dip. "It’s a creative artist’s space," he tells The News on Sunday, in an exclusive meeting, while on a brief visit to Lahore.

Architectural spaces and communities feature prominently in his works which, Anwar admits, seeks to "engage the spaces of human interaction in public and private environments."

The News on Sunday: For the uninitiated, how would you define digital/new media art?

Faisal Anwar: Well, I can’t give you any one definition. By and large, new media is technology-driven, or responsive to the environment. Again, it’s a very broad definition. Technology is so many things -- motion sensors, physical computing, touch- or gesture-based responsiveness, also camera and sound, etc. One thing in common is the responsive nature of it. Besides, it isn’t linear. Your art work is responsive to your input -- that is, if you walk up to it, its form will change.

In contemporary mediums, we have a cell phone, if we tweet from it, it goes to a hashtag which records it, and it becomes part of the global network. So, everything that has these digital inputs, which you can pull in in physical computing and manipulate, based on certain criteria, is what we’re calling new media.

TNS: What are your subjects, generally?

FA: To answer this, we’ll have to go back to when I started work in 2006-07. My father [sitting in Pakistan] often asked me about my life in Canada, and I’d wonder how to share the experience with him. Of course, I could Skype, but that might not be enough. What if he wanted to feel the environment? There were such multi-layered factors I was looking at.

During the same time, while on a residency at the Banff New Media Institute in Alberta, I got fascinated by odd architectural spaces -- elevators, hallways, buildings, such temporary spaces where we spend a bit of our life’s time and move on, the odd encounters that we have became my early subjects.

In 2008, I was invited to develop a project with VASL Artists Collective, Karachi, and an artist-run company in New Delhi, India. Titled ‘Odd Spaces,’ it sought to connect people in different parts of the world by removing stereotypes, preconceived notions, and a definition of ‘others’ that we form so easily. We equipped the gallery spaces on three different locations -- Karachi, Delhi, and Dhaka -- with sensors and cameras, and streamed video in real time.

Back then, we didn’t have a lot of technology. By technology I mean bandwidth. The sms protocols that we had were also of very primitive levels. Besides, Twitter wasn’t as accessible as it is today. So, we had to play with whatever communication tools were available to us. The goal was basically to start a conversation.

It kind of became a research for me. Later, I put together a similar multi-disciplinary exhibition, connecting Karachi, Dhaka, and Vancouver in a gallery space. So, this was growing. Technology was also growing along the way. Parallel to this, Twitter was becoming popular. For my next project, I put up this large, animated tree, which has no leaves, and each leaf represents a tweet from a different part of the world. The idea was that the more data you plug in, the tree starts to grow. Here, the people wouldn’t see each other but together they were creating a narrative. We named it ‘Tweet Garden.’

TNS: Does the ‘new media’ offer any challenges to you?

FA: Our primary challenge is that we’re working with technology but we don’t want to show technology. Because technology is just a medium or tool. Our work isn’t about technology, it’s about conversation. The problem arises the moment you show how the work is happening. If there’s something showing on a projection screen, it has a wow factor involved, but our goal is to constantly move away from it, to try and achieve a balance, and show that it’s not technology we’re interested in.

TNS: Cities and gardens are a recurrent theme in your body of work. Comment.

FA: You’re absolutely right. Gardens, trees, clouds, organic forms, cities, and communities have always fascinated me. Even when I was in NCA, my work was mostly narrative-based. We used to do puppetry and storytelling. The idea of reaching out and finding a way to know someone was a part of my personality.

More recently, I developed a video game for kids for which I got seed money. It’s aimed at learning about landmarks of the city through art and music. A street in Toronto was the first street in it. I’m adding Pakistani streets too. Choku, the main character, is an explorer. The game has puzzles and embedded landmarks in it.

TNS: Are you currently self-employed?

FA: Yes, I’ve been self-employed for the last seven years. I have a company in Canada, called Digital Dip; a creative studio space. I do consulting work with technology companies, mostly in Silicon Valley. I produce and develop their user experience for their softwares helping them understand personification, usability issues, and how to conceive interface which is for cross-platform -- from mobile to desktop to physical space.

TNS: Does VR [Virtual Reality] appeal to you?

FA: No, it doesn’t. I don’t like the device -- that physical object which you wear; I think it takes something away from you.

TNS: You also made documentary shorts. Tell us something about them.

FA: Video has always fascinated me. I’ve produced short, experimental films, and showed them in different festivals. One movie, Clifton To Saddar, which I made in Karachi, is about a journey in the rickshaw. It was a 60-second-long film. I made it a kind of a time-lapse story, recorded the entire journey in real time, then squeezed it in and played with the frame rate. It had some really interesting characters I came across on the way, and their little, little responses.

TNS: You did a residency at a film centre also?

FA: I went to the Canadian Film Center where I enrolled for their seven-month long Interactive Media & Entertainment Program. Basically, it’s not a film school but a kind of an incubator where they invite researchers, artists, designers, filmmakers, programmers, and give them mentorship to conceive their projects.

TNS: An artist whose work inspired you in particular?

FA: I love Rashid Rana’s work. It’s very sensible, very creative work. There’s a lot happening in his art. I also like the works of the Canadian installation artist David Rokeby; he’s a pioneer on many things.

TNS: Finally, what brings you to Pakistan?

FA: I keep coming back to Pakistan. My father, my brother and his family are based here. Later this year, I’m coming to Karachi for a longer time, for Karachi Biennale. I’m exploring ways to develop the game here.