Thirty-five-year-old Raja Arif Minhas greets visitors at the reception desk of the Pak Kashmir Guesthouse, situated on the first floor of a dilapidated building on one of the busiest streets adjoining the Lea Market on Lyari’s Sheedi Village Road.

The guesthouse provides accommodation to labourers. It does not offer delicious food or comfortable beds or free Wi-Fi. Traders and labourers from Balochistan stay at the guesthouse for brief periods. During that time, they go out in the morning and return in the evening to rest.

Minhas collects rent and sometimes mediates in disputes among the guests. But some visitors still approach him for the purpose the building was used for a few years.

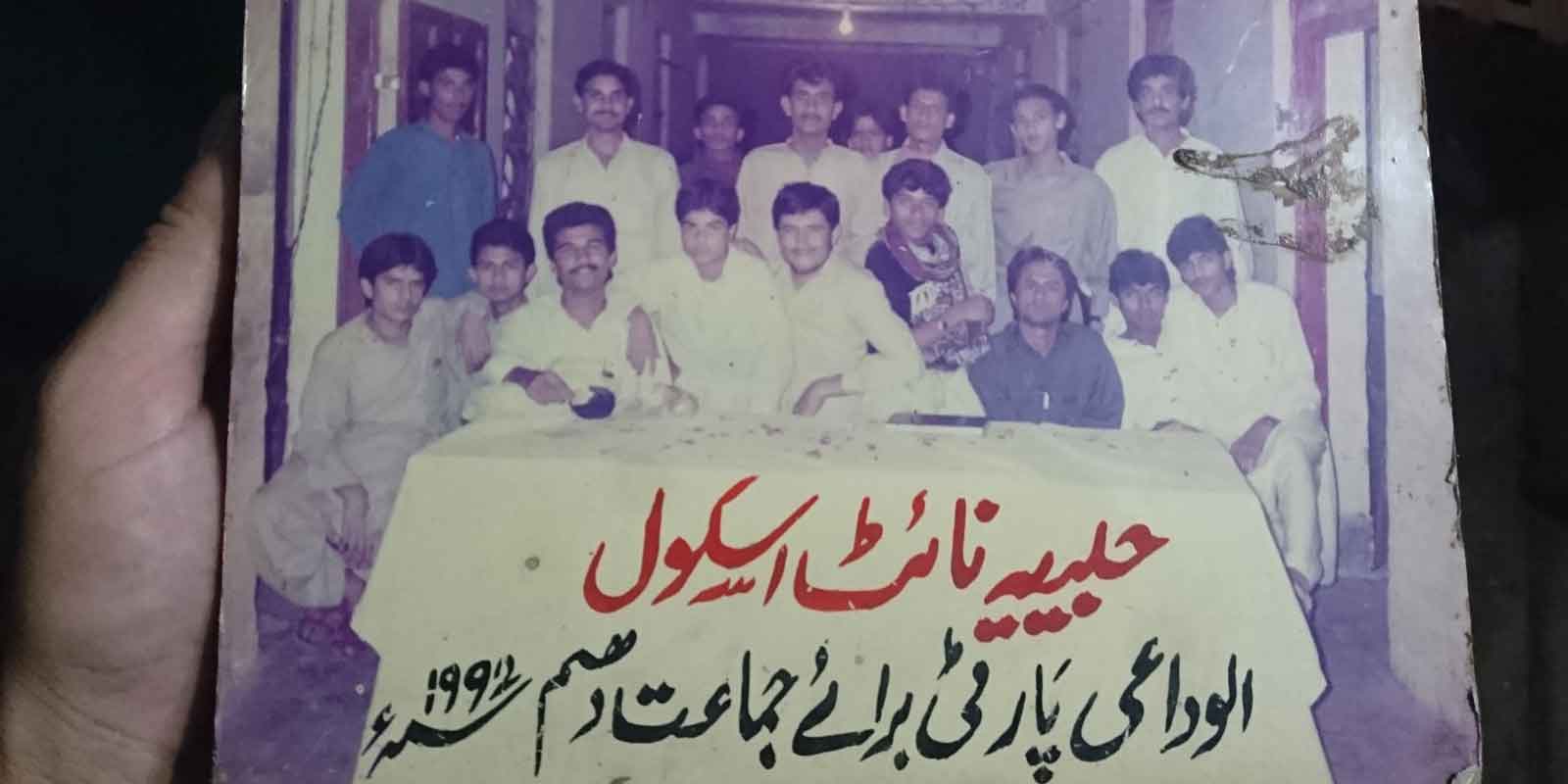

“Every week I come across such people,” he told The News. “Once this building used to house the Habibia Night School, the only regular night school of Karachi.” He said the school’s founder Amanullah Khan himself had had to take the decision, with a heavy heart, to close the school. “It was not only the end of an institute that had served Lyari’s residents and migrant labourers for more than half a century, but also the end of a visionary’s dream.”

Kashmir Night School

Amanullah Khan, a veteran politician from Kashmir and an educationist, reminisces in his autobiography that after he quit teaching at a private school, he started his own institute in 1956.

Initially named the Kashmir Night School, the institute registered 10 students within a few weeks. And the number kept on increasing, making Khan look for a structure where he could move the school to. That’s when he found the building near his temporary school that was to home his institute for five years.

The structure was already being used for a day school by the Habibia Educational Society (HES), who owned the building as well. The society was named after the assassinated Afghan emir Habibullah Khan and was run by the Afghan community living in the area for decades.

Amanullah Khan’s request to run his night school in the building was accepted on the condition that he would rename it as the Habibia Night School, which started running there in 1957.

A difficult journey

Later on, Amanullah Khan and the HES developed differences over the school’s management. The society tried to evict him from the building, but he continued running his institute. “Those were the hardest days of my life,” he writes. “I was only trying to run a school, and the police would show up to arrest me.”

Khan formed the Gilgit Educational Society and then the Habibia Night School started functioning under it. In Gen Ayub Khan’s regime, then minister for refugees’ rehabilitation Lt Gen Muhammad Azam Khan set up a regional municipality office and a marketplace on the site of the old fruit bazaar near the Lea Market.

“I tried to acquire the unfiled rooms from the government to accommodate my school there,” writes Khan. “In the beginning of 1962 I moved the school into the empty rooms of the newly constructed building.”

In 1965 he started intermediate classes in the evening shift and a morning school, the Merry Dale Primary School. The students’ enrolment reached up to 1,700. Most of them were labourers and uneducated adults from Lyari’s nearby areas. After Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s nationalisation policy was implemented, Khan’s morning school was nationalised, but his night school was spared.

Kashmir movement

In 1976, after Amanullah Khan fully functionalised the night school, he went to the United Kingdom to actively participate in Kashmir’s freedom movement. As his involvement in the institute’s affairs reduced, so did the number of students: from thousands to hundreds.

Khan’s educational activities were not separate from the movement to free Kashmir. The organisations associated with the movement used to convene their meetings and elections on the school’s premises, with easy access to the telephone, typewriter and others facilities.

Closing chapters

Even after Amanullah Khan’s return in 1986, his political activities and its implications affected his work on the education front, bringing about the closure of the New Merry Dale School in 2002. The night school, however, continued until 2014, when a grenade attack by a criminal gang in Lyari closed its chapter forever.

Arif Minhas recalls the fateful days when Lyari was under the influence of criminal gangs. The shops on the ground floor of the building in which the Habibia Night School ran used to get extortion calls. Refusing them would result in target killings and grenade attacks.

In the 2014 attack, the school’s main entrance was damaged and a boy working at a teashop lost his life while many others were injured. It was then that Khan decided to close the school.

A success story

Sufi Jahangir Shah, an alumnus of the night school, told The News that he quit primary school after his father passed away in 1997. Shah was 11 years old at that time.

He left his native town Pishin and moved to Karachi, in the Lea Market area, where he started working at a dry fruits shop. Between his loading and unloading of heavy sacks, he often wished he could have continued his education so he would get a better job.

Fortunately, he found out about the Habibia Night School. He completed his primary education from the institute in the next two years. “Now I am able to note down addresses and understand simple calculations,” he said. “Almost all my classmates were labourers working during the day and attending classes in the evening. After two years, I went back home with my primary school certificate.”

He returned to Karachi after two months and re-enrolled himself at the school to continue his education. He matriculated in 2002. Now he owns his own dry fruits business at the Lea Market. “I tell my story to every employee working at my shop”.

A grim situation

“[Amanullah] Khan sahib wished to set up his schools in other parts of the city,” recalled Arif Minhas. “I would like to follow in his footsteps, but I don’t have enough resources for renovation, teachers and furniture.”

The building of the guesthouse is no longer in a condition to house an informal school. Plaster is crumbling down from its ceiling. The peeling walls look filthy. The floor is cracked. The rooms stink. Most of the alumni still ask Minhas about their certificates, but he has no record of them. “When the school went into the hands of gangsters, they destroyed the school’s records.”