'Obesity could be a neurodevelopmental disorder'

Recent study team claims early chemical processes of brain development are probably a significant factor in determining risk of obesity

Obesity is one of the leading causes of poor health worldwide and has rapidly increased to affect more than 2 billion people over the past few decades.

Despite decades of research on food and exercise routines, many people still struggle with weight loss. Now that they think they know why, researchers from Baylor College of Medicine and allied institutions contend that the focus should be moved from treating obesity to preventing it.

In the journal Science Advance, the study team claims that early chemical processes of brain development are probably a significant factor in determining the risk of obesity. The genes that are most strongly linked to obesity are expressed in the developing brain, according to previous significant human studies.

Epigenetic development was the main subject of the most recent mouse study. Epigenetics is a molecular bookmarking system that controls whether or not specific cell types use genes.

The corresponding author Dr Robert Waterland, professor of paediatrics-nutrition and a member of the USDA Children's Nutrition Research Center at Baylor said: “Decades of research in humans and animal models have shown that environmental influences during critical periods of development have a major long-term impact on health and disease."

“Body weight regulation is very sensitive to such 'developmental programming', but exactly how this works remains unknown."

According to first author Dr Harry MacKay, who was a postdoctoral associate in the Waterland lab while working on the project, the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus, a master regulator of food intake, physical activity, and metabolism, was the focus of the study.

They found that early postnatal life involves significant epigenetic maturation in the arcuate nucleus.

Before and after the postnatal critical window for the developmental programming of body weight closed, the researchers carried out genome-wide assessments of gene expression and DNA methylation, a crucial epigenetic marker.

The fact that they looked at the two main groups of brain cells, neurons and glia, is one of their study's strongest points, according to MacKays. It turns out that these two cell types' epigenetic maturation is significantly distinct from one another.

“Our study is the first to compare this epigenetic development in males and females,” Waterland said.

“We were surprised to find extensive sex differences. In fact, in terms of these postnatal epigenetic changes, males and females are more different than they are similar. And, many of the changes occurred earlier in females than in males, indicating that females are precocious in this regard.”

The biggest shock occurred when the researchers compared their mouse epigenetic data to human data. The genomic regions in the human genome linked to body mass index, a measure of obesity, corresponded significantly with the genomic regions targeted for epigenetic maturation in the mouse arcuate nucleus.

-

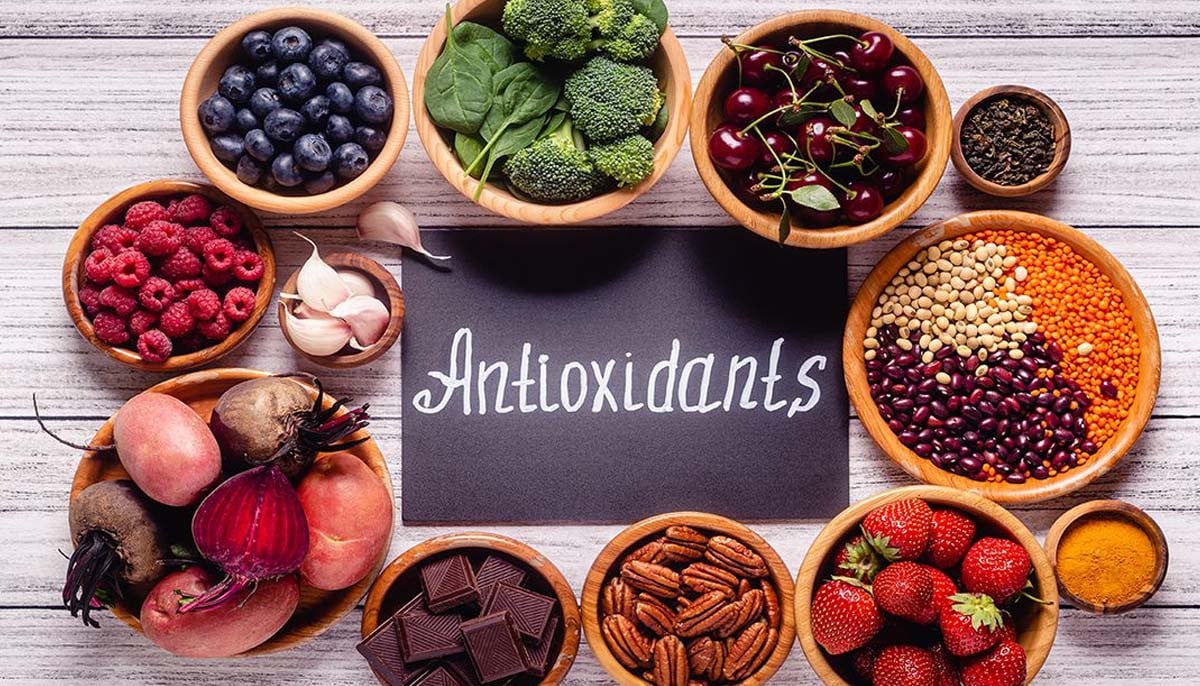

Antioxidants found to be protective agents against cognitive decline

-

Coffee reduces cancer risk, research suggests

-

Keto diet emerges as key to Alzheimer's cure

-

What you need to know about ischemic stroke

-

Shocking reason behind type 2 diabetes revealed by scientists

-

Simple 'finger test' unveils lung cancer diagnosis

-

Groundbreaking treatment for sepsis emerges in new study

-

All you need to know guide to rosacea