The ban on Manto goes to show how uneasy we still are with the idea of free artistic expression

Wasay Chaudhry has resigned from the task force that was set up on the arts, particularly in reference to films. The reasons for his leaving the force are not difficult to guess.

Whenever a new government takes over there is a flurry of activity in all sectors. In the arts, too, good intentions are expressed and initiatives undertaken with a high resolve, but it then all peters out: suggestions just adorn files and no tangible action is taken.

This government in particular has taken unprecedented steps towards the setting up of task forces. They actually seem enamoured by the idea. In every sector of life, the government has a task force that is supposed to come up with quick fixes for the work in hand. Various experts from the field are collected together and they start to work assiduously and with a certain naivety to set the world right. After a few meetings and a few months, it all begins to lose steam as the invaluable suggestions and proposals collide with the reality on ground.

In its dying days, the Nawaz Sharif government announced a culture policy and its entire thrust appeared to be films. It was being assumed that the revival of cinema would be a catalyst for the wholesome expression of art in all its fields. Since there was not sufficient time for the government, all the policy was not implemented and it also remained restricted to files.

All governments think that emphasis on infrastructure is more important and making theatres, cinema halls and art galleries boosts artistic activity in general. The infrastructure projects are visible while the focus on human development is not.

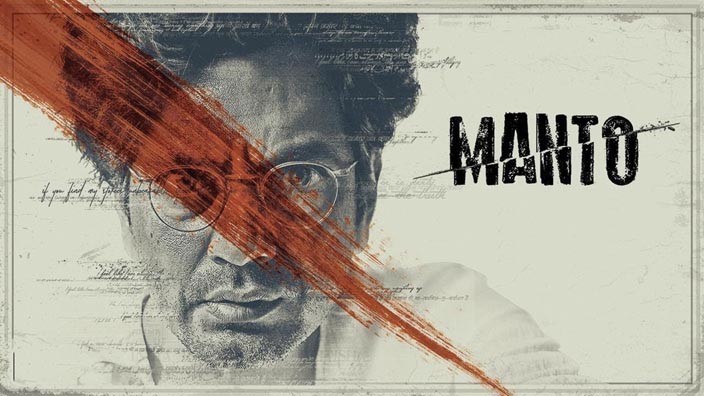

But the most important aspect of art is freedom of expression. The more the society is willing to create a space for itself artistically, the greater the possibility of something substantial happening. These days there is a raging controversy about the film Manto, which is not being allowed to be publicly screened in the country.

Manto, like many other writers and poets, sits uncomfortably with the country’s establishment. He said the truth and perhaps truth is not palatable and therefore he was bounded in his lifetime. But of late there has been a rehabilitation of sorts of his image, reputation and literary contribution. Many of his stories have been enacted, made into dramatic presentations, and he has also been widely translated. But

still there’s something that rankles.

And then this film was made in India. A film about writers who expressed with a no-holds-barred attitude can be seen to be subversive. There must be a hidden agenda by the enemy to rundown Pakistan and to denounce it publically.

Nandita Das has been a very prominent filmmaker of India. She has often visited Pakistan and is liked by the people she has worked or associated with -- but there must be something sinister in her intention to make a film on Manto.

The task forces usually comprise of people who are experts in their particular fields. But usually they are more like technicians. What they lack is the commitment of a cause. They probably can be hired for the job or in carrying out a particular assignment. Either they are not fully aware of the local conditions or they end by forming a very uneasy relationship with the bureaucratic establishment which is already well entrenched and usually entrusted with the task of implementation.

One wonders, whether in something as organic as the arts, task forces can be of any help. What is important is to create an enabling environment and then let the various creative forces play their part. In the past, in many countries, including Pakistan, there has been an emphasis on the government laying down a certain order, which is then implanted top down. This is generally a fabrication which comes in the way of an organic development of cultural expression.

It may be asking too much for the government to spend on the arts and then allow them to function on their own without any interference. Usually the institution that doles out the cash considers its right to be directional about the entire effort. It would be ideal if the governments don’t interfere in the freedoms of the arts after seeing them grow and prosper under its aegis. This can come in many shapes, for like in India, there is now an increasing drive to put a stamp of a certain ideology and it is obvious that the institutions run by the government would be forced to toe the line. In Pakistan too there is a general tendency to clamp down on a certain ideological framework and any deviation from it can be snuffed out in the name of national interest or religion.