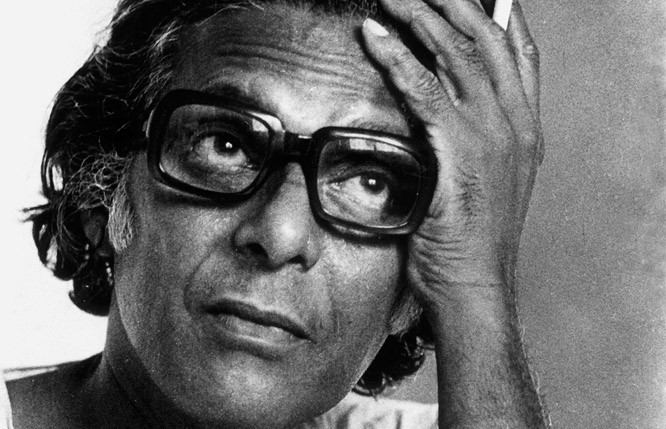

The director Mrinal Sen who died last week was one of the greatest Indian directors of what was then known as parallel cinema

Mrinal Sen who died last week was arguably the greatest Indian director and one of the greatest directors of cinema in the world. With Satyajit Ray and Ritwik Ghatak, he formed a triumvirate of Bengali directors who put the Indian cinema on a pedestal that was recognised for both its innovative themes and unique development of the language of cinema.

But his cinematography was not just unique for its experimentation with the developing technological scope of the equipment involved in cinema but its ability to explore a nuance, an attitude, a behavioural pattern or a prejudice so deeply embedded as to be considered a virtue or a value. His cinema boldly questioned many issues deeply ingrained in society that he belonged to and was familiar with, but at the same time he never denounced the ethos that made him what he was. To many it may seem like a contradiction, but to him it was two sides of a coin, and the acceptance of some and the rejection of others was part of a process that involved more than mere consciousness or rationality.

This is what he shared immensely with the other great Satyajit Ray: the full scope of the dilemma called human beings who he did not see exclusively from the lens of an ideology. It is being stressed because he was a Marxist to the core and remained so till the very end but he was also a film maker, a creative animal who took his artistic concerns more seriously than his ideological faithfulness. His understanding of human nature was a quest and the evolving shape of behavioural patterns was a work in progress, treated sympathetically and not as renunciation or mindless rebellion.

Satyajit Ray was not an avowed adherent to any ideological point of view, and like many others thought that ideological faithfulness was limiting and failed to look at human dilemma in its largest possible scope, in all its dimensions, instead forcing one to choose a certain standpoint. In it he was largely following many others who were non-committal, so to say, but outstanding in touching the visceral, and striking the right chord.

Mrinal Sen was a communist but he too broadened the scope of his understanding rather than seeing it through the blinders so many had to struggle with. Ideologically inclined people see it as a betrayal of their core ideological alignment but for Mrinal Sen human beings came first and the ideological framework later. He saw no difference or paradox between the two.

He was thus not a director of broad sweeps but of finer strokes. His works did not consist of larger-than-life visualisation of certain critical moments in human history or larger than life treatment of characters. His works were not like October or Ten Days that Shook the World but centered round small gestures and the unsaid, fully grounded in the local ethos.

He was more known to the Bengali cinema goers till he became internationally acclaimed after making a few films for mainstream Indian cinema. Some films that he made were seen as breakthroughs, falling in line with what was labelled then as parallel cinema. They were well-received critically and introduced him to the larger swarm of viewers of films in its broader sense. Khandhar and Genesis were both masterpieces and left an impact that only a serious and sympathetic study of humankind can.

He won many awards like The National Film Awards for Best Features film 1969: Bhuvan Shome, 1974: Chorus, 1976: Mrigayaa, 1980: Akaler Sandhane and National Film Awards for Best Direction in Bhuvan Shome, Eik Din Pratidhin, Akaler Sandhane, Oka Oori Katha and Khandhar. Among the Filmfare awards he won the Critics Awards for the best film, best director and eventually Lifetime Achievement Award.

The international awards include Silver Prize from Moscow International Film, Special Jury Prize from Karlovy Vary International Film Festival, Interfilm Award and Grand Jury Prize from the Berlin International Film Festival, Jury Prize from Cannes Film Festival , Golden Spike from Valladolid International Film Festival, Golden Hugo from Chicago Film Festival, Special Prize of the Jury from Montreal World Film Festival, OCIC and Special Mention from the Venice Film Festival and Silver Pyramid from Cairo International Film Festival.

In 1979, he was awarded the Nehru Soviet Land Award by the Union of Soviet Socialist Republic for his contribution to world cinema. In 1981, the Government of India awarded him with the Padma Bhushan, President of France awarded him the Commander of the Order of Arts and Letters, the highest civilian honour conferred by that country, in recognition of significant contributions to the arts, literature, or the propagation of these fields. In 1993, he was awarded an honorary D. Litt. by the University of Burdwan and an honorary D. Litt. by Jadayour University in 1996. In 1999, he was awarded an honorary D. Litt. By Rabinda Bharati University. Between 1998 and 2003, he was made an Honorary Member of the Rajiya Sabha. In 2000, President Vladimir Putin honoured him with the Order of Friendship. In 2005, he got the Dadasaheb Phalke Award, the highest honour given to an Indian filmmaker. In 2009, he was awarded an honorary D. Litt. by the University of Calcutta. In 2017, he was inducted as a member of the Oscar Academy.