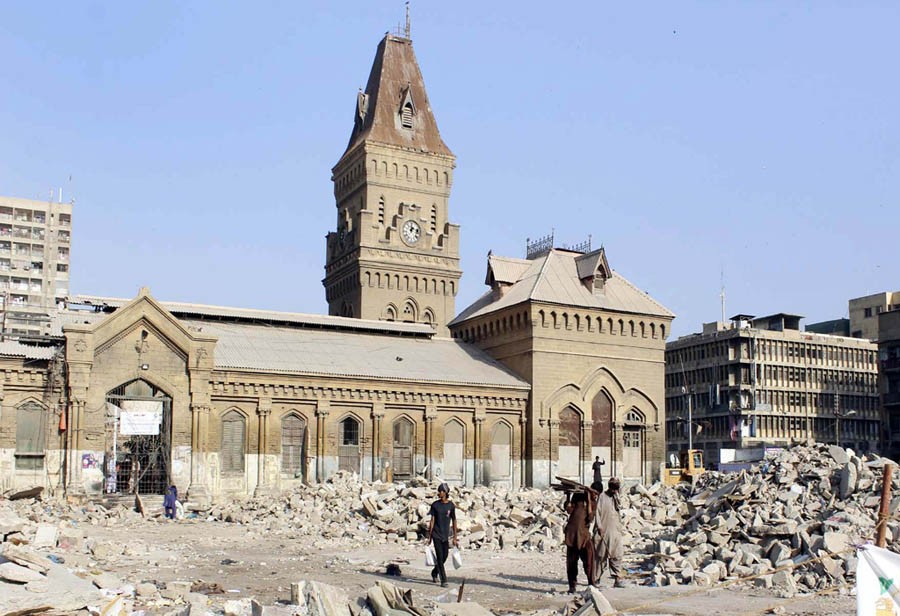

Empress Market is ‘cleaned-up’. Now, only rubble remains

Empress Market: the hub of chaos you could enter for its sensory stimuli, whether you actually bought something or not. Second-hand clothes, glittering jewels and trinkets, the heady smell of spice, the clatter of the meat market, the birds rattling in their cages. Everything imaginable under the sun was available here, the one-stop original mall to furnish your shopping needs, from groceries and household supplies to dyes and kites and cosmetics. I never failed to find the original Hashmi surma here, or even better, small stones that melted into kohl. But mostly I came here for the old Irani cafe, tucked beside a lane of meat and vegetable shops, its ceilings intact from before partition, the chai so steaming and perfect.

But now everything is gone. Only rubble, sending clouds of dust into the air as the anti-encroachment drive continues. Cats that I remember feasting on scraps from the butcher’s stalls are meowing confusedly through the debris, as if wondering what happened to their steady supply of food. In less than a week, bulldozers have razed over 1,400 shops around Saddar, and removed over 4,000 hawkers. The grand operation is part of a city-wide ‘clean-up’; on the orders of the Supreme Court, the Karachi Metropolitan Corporation is clearing all illegal businesses, including the ones that have existed for over 50 years.

Inside Empress Market, a man sits beside a heap of crates filled with fresh vegetables: chillies, potatoes, lemons, ginger. It is a curious burst of colour amidst the fallen brown and gray. "Just want to sell some vegetables if I can," Mohammad Bilal explains, "We’ll go when the police comes." Bilal is from a family of vegetable sellers. He learned the trade from his father, who in turn learned it from his. For 50 years, their family shop had stood in this exact spot. They had 10 other men under their employment earning around Rs1,000 a day. Along with Bilal’s family, those men too will now have to find work elsewhere.

Every morning, Bilal and his brothers would arrive at the market at 6am, bearing the day’s supplies of vegetables from the mandi. But on Nov 11, the day the razing began, they weren’t even allowed inside. The bulldozers had begun their duty at 2am, but no one had informed the vendors. No notice, no time to safeguard their belongings. "Where is the dignity in this?" Bilal laments.

The group of men around Bilal draw closer, and join our conversation without being asked: they have so much to say. "We’ve been paying rent for 50 years -- where are we to go?" "They’ve removed windows, broken iron bars, taken our things." "When Shahabuddin Market [in Sadar] was shut down at least they provided space for relocations, where are the arrangements for us?" The circle expands, more men are pulled into it -- talk to this guy, he was a construction worker here, he made money lugging around people’s purchases; talk to this guy, his family has been here since 1889, one of the few whose business will not be stripped down. The man in question is Anwer, a 72-year-old who did his Masters in Economics, but abandoned that trajectory to help run the family grocery store in Empress Market. He doesn’t have to worry about losing his business, constructed under the pakka section of the market. He is not particularly offended by the clean-up, "Well, the shops were running on bhatta…" but then he pauses, "In the name of humanity though, maybe it’s not so right."

In the early days, Anwar says, the market consisted mostly of Ismailis and a few Parsis. But then people from all sorts of backgrounds started showing up -- Sindhis, Punjabis, Pathans, Mohajirs. They were like a family. "A joint business," chimes in Waseem, Bilal’s older brother. "Everyone was tied to everyone else, and we all co-existed peacefully! Where else in Karachi have you seen a community like that?" Now they will be forced to disperse. And those who cannot afford rent outside, Waseem asks, "where will they go?"

"Gareebon ka khoon pee rahay hain," says Nadeem, most vocal and angry among the band of men. He was the chowkidaar here. As Nadeem passes around cups of chai, Waseem explains that the various vendors pooled in money to pay his salary. Now, like the rest of them, he was jobless. Empress Market was host to a unique ecosystem of co-dependency, and now the whole thing had fallen apart. As for the promise of what would take its place -- the men feel it is a scam. The colonial structure was built during the British Raj, between 1884 and 1887, to commemorate Queen Victoria’s golden jubilee, and rumours have been circulating of renovations that will restore the building to its former glory, and turn it into a museum, or some sort of public site with wide promenades and even restaurants. Essentially, "beautify" it. Online and on TV, people are heralding this as good news. But the vendors of Empress Market are not convinced; they claim that channels are only interested in spectacle, anything that will further their own business interests, while the Pakistani people do not really care for the poor, only want them out of their sight.

"This is all in the name of Naya Pakistan," Nadeem complains, and the rest nod. "Who wants a Naya Pakistan? Was Pakistan not new when the Quaid made it?"

The men intend to hang around for a few days, but really, they are preparing to leave. Bilal hopes to make some sales, which I’m skeptical about, but just then two women walk through the broken gate and approach him. Outside, the van of uniformed men has not moved from its place. Stiff and straight, a few stand with their shoulders drawn, their eyes on the market. Their khakhi shirts say ‘City Warden Karachi’. One of them, Faraz Ahmed, explains that they show up every day to ensure safety. "Nothing should be taken from inside the market, nothing damaged." Just the other day, someone tried to sneak out some materials, they had to summon the police. So they keep vigil until asr, at which point the area is closed off, the police and rangers show up and patrolling begins. Faraz’s superior inches closer, but does not add to our conversation. "It’s good that this happened," Faraz says. "There was too much tension for people, too many traffic jams -- now everything will improve."

As for the vendors, he is not worried. "Mayor sahab has promised, these men will be given alternate spots." As Faraz answers my questions, the superior smiles reservedly at us, watching every word of the young boy.