As our day of independence, when a new political entity by the name of Pakistan emerged on the world map, August 14 holds integral significance in the lives of our people.

But after a lapse of 71 years, one may aver that August 14, 1947 is variously represented in our various discourses. It was the day marking the birth of a new state and partitioning of the subcontinent, entailing blood-letting, rape and plunder at an unprecedented scale. Thus, the memory of that event is one of rejoicing because Pakistan was born. Along with this, there is a sense of mourning because Partition and the mass exodus which the subcontinent witnessed constituted a tragedy of a colossal magnitude.

Therefore, the expression of gratitude to the Almighty for granting independence is entwined with a sombre feeling of loss and nostalgia which is depicted by authors, historians and poets from both sides of the border.

Such multiple readings of Partition of India and the birth of Pakistan have made it into a rich theme even after 71 years of its happening.

If I may be allowed to draw up two broader categories about the way August 14 has been depicted in the national narrative, those would be -- sacrifice and tragedy. Pakistani state narrative emphasises ‘the sacrifice’ of Indian Muslims as the decisive feature of Independence. Nasim Hijazi’s Khak aur Khoon, Razia Butt’s Bano and Bano Qudsia’s Abaad Weraney are some of the famous illustrations of this trend.

The state narrative’s privileging of sacrifice over tragedy was probably the reason why a Pakistani celebrity objected to the recitation of the famous partition poem Ajj Aakhan Waris Shah Nuu by Amrita Pritam at the inauguration of a seminar on Partition at the School of Oriental and African Studies, London. That poem is ritualistically recited at any international conference or seminar on the topic of Partition outside Pakistan.

The reason for decrying that poem was its lamentation over the severing of the Punjab and Punjabis which does not sit well with the Pakistani narrative of celebration and deliverance. For us Pakistanis, as per the state narrative, all the misery conjoining Partition was the ‘sacrifice’ offered by Muslims to secure a homeland in the North West of the subcontinent. It was a means of deliverance from the oppressive British rule and from the possibility of subjugation to Hindu rule.

Before proceeding any further, the subtle distinction between a tragedy and an act of sacrifice needs to be stated here. To me, sacrifice is utilitarian in essence, in particular when contextualised in terms of the event of Partition and mass migration. You make a sacrifice, leave your home and hearth, abandon your ancestral neighbourhood, and get a reward for this sacrifice, which in our case is the country called ‘Pakistan’. Thus, it becomes utilitarian because of the promised end in a reward.

Tragedy, on the other hand, is an event causing suffering, destruction, and distress. But it does not necessarily yield any tangible (you may read it material) outcome. One, however, must not rule out the civilisational effects that tragedy engenders. If internalised into the collective consciousness, tragedy is, in the words of Prof. Ashfaq Sarwar, the ‘greatest human value’.

Empathy is the most enduring result of tragedy. It also imparts to people lessons in human inclusivity. It is the most potent instrument for communities and nations to attain civilisational maturity, which is mostly articulated through art and literature. Saadat Hasan Manto’s Khol Do and Toba Tek Singh, Ashfaq Ahmad’s Gadariya and Krishan Chander’s Ghadar are representative pieces of literature around the tragedy of Partition. Khadija Mastoor’s novel Aangan can also be mentioned here as an important piece of literary excellence, which was written against the backdrop of human relations being re-negotiated in the wake of Partition. Aag Ka Darya by Quratulain Hyder is another such masterpiece.

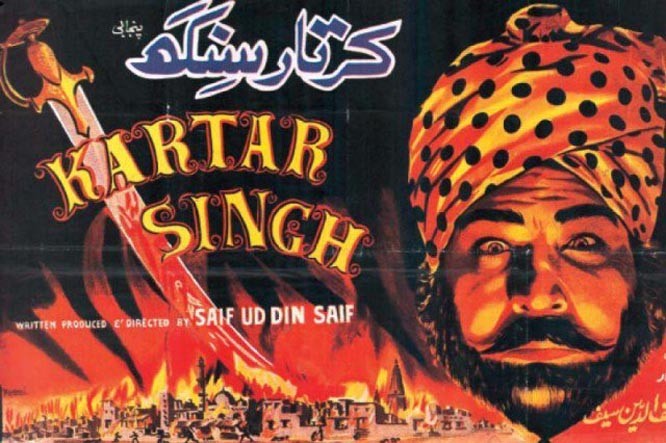

When it comes to films, Kartar Singh springs to mind instantaneously. A Punjabi film produced in 1959 by Saifuddin Saif, it is one of the most powerful artistic representations of Partition. Late Alauddin played the main character and he was catapulted to trans-national recognition and fame. It provided extremely traumatic depiction of the severing of human relationships that were caused by Partition.

I vividly remember Pakistan Television ran a serial in the 1970s by the title of Taabeer. A story very well told, its main theme was sacrifice for a Muslim homeland. All said and done, Partition had a stirring effect on every genre of art and literature.

Nostalgia is another important outcome of the tragedy manifested in the form of Partition. Intizar Husain made nostalgia into his forte and used it in a dexterous manner in his literary works. But to my reckoning, Mushtaq Yusufi’s Aab-i-Gum is the best example of nostalgia emanating from the event of Partition.

Interestingly, in several cases, the ‘presumed’ boundaries between sacrifice and tragedy tend to blur. Mukhtar Masud’s works, particularly his last book Harf-i-Shauq, is one such book which deals with the author’s days spent in Aligarh. Masud is ranked among those authors who are unequivocal in asserting the indispensability of the spirit to sacrifice for securing a homeland for the Muslims. But even he could not divest himself from the nostalgic yearning for the past, which has a visible presence in his first book, Awaz-i-Dost.

Nostalgia, in fact, provides a link between those who see Partition as a tragedy and others who consider that event as sacrifice, seeing in it the same spirit that was manifested at the time of the Prophet’s migration from Mecca to Medina.

Muslims of every intellectual stripe were irked by the fact that many of the socio-cultural symbols were left behind in India. Delhi, Agra, Hyderabad, Amjer and Aligarh had been the fountainheads of South Asian Muslim civilization, and parting with them became the principal source of nostalgia among the Pakistani migrant communities.

To conclude, there is a need to underscore the importance of a middle ground between sacrifice and tragedy -- to be identified by artists and writers. It may allow them more creative space to flit between and come out with a fresh analysis of that event which undoubtedly was momentous in its magnitude and proportion.