Religion, modernity and dargah

In the South Asian Muslim context, the rationalised emphasis on the sanctity of the text resulted in crystallised, sectarian interpretations. The rise of Deoband among the Muslims, and Brahmo Samaj and Arya Samaj (in particular) among the Hindus, along with other reformist movements, was a direct result of colonial modernity. The pluralistic institution of the shrine -- respected in the cultural epistemology of both Islam and Hinduism -- was replaced by the exclusionary religious reformist movements of the nineteenth century, thereby creating a vacuum where the centuries-old traditions of cultural assimilation had existed.

Thus, one Indo-Persian culture, cultivated over centuries, was replaced by the identity politics of Muslim and Hindu culture. The dargah was a part of the lived experience of the subcontinent’s citizens, whereas the mosque or temple did not acquire the sense of communal harmony that they claimed.

In this context, it becomes possible to make an important assertion: culture, when de-historicised, loses its common touch. If culture is ordinary, and popular, that is, if culture is a phenomenon practiced by the majority of a people, its assertion must be in the realm of the majority, i.e. culture is the dominant mode of practice among the people living in a space.

The social context of modernity imposed the cultures of a dominant but minority elite onto the South Asian polity as a whole. Both Muslim and Hindu elite had their lifestyles assimilated with the British colonisers’ culture, and the resultant culture was then imposed on the people of the subcontinent.

Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Nawabzada Liaquat Ali Khan, Jawaharlal Nehru, Sir Ganga Ram, and other luminaries were in significant ways parts of the social and financial elite. Their lives were predominantly shaped by their British education, and by their closeness to the Muslim and Hindu elite as well. Their connection with the British elite was a significant part of their epistemological training as well as their very being. This onto-epistemic duality in their case was not a rupture, but a defining feature of their personalities. I believe these men shaped the entire history of the subcontinent precisely because of this multiplicity of influences. Their reconciliation of opposing historical forces created the de-historicised conception of culture and identity that has defined the subcontinent since independence in 1947.

The kind of forced unification of cultures, imposed upon the public since 1947, creates what I call ‘arrested modernity’. Whereas the Western world managed to become modern in a rationalised way, the subcontinent got stuck between the modern impulse and the traditional mooring that the East prides itself on.

In other writings, I have argued that Muslim reformers used modern (scientific) instruments to reinforce the religious tradition. The printing press, loud speaker, and railway contributed significantly in the establishment of religious sway on the people. Later, I had to revise my contention as I realised that the very tradition on which the whole edifice of contemporary Islam was built was itself re-invented in the light of modernity.

I must underscore that the relation between religion and modernity is important to explore here because ours is an ideological state, founded on religious ideology. Therefore, all discussion of culture must be circumscribed by a discussion of ideology.

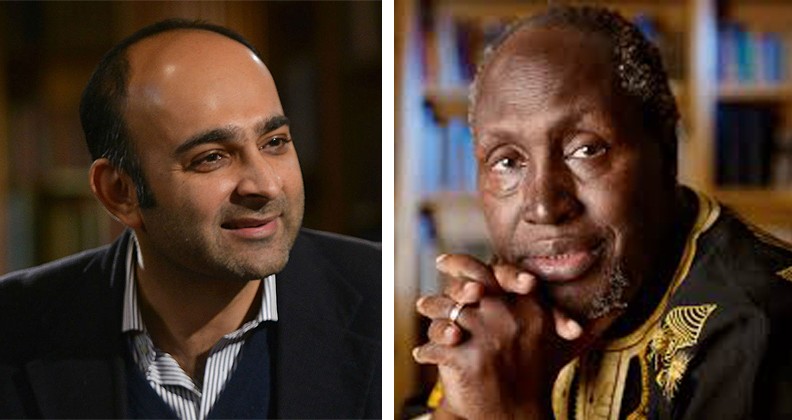

When the socio-political landscape is bound up in ideology the way it is in Pakistan, the only space available for negotiation of power is the space of culture. Culture, in such an instance, becomes the place where pluralism becomes possible. This brings me back to Mohsin Hamid, who argues that the plurality of cultures is one of our great strengths. Where state apparatuses aid and abet the exclusionary structures of the socio-religious complex, cultural practices make it possible for the polity to assert inclusionary tendencies. For example, in the spiritual space of the dargah, pluralistic tendencies were possible before the dargah was replaced by other institutions. Basant is reported to have originated inside the dargah space of Khwaja Nizamuddin Aulia of Delhi, and can be read as a reaction to the religious belief that the ‘saffron festival’ was essentially a Hindu custom. Dargah thus becomes a celebration of cultural pluralism, assimilation, and accumulation.

Culture, then, is more a salad bowl than a melting pot. In cultural studies, the traditional concept of large cosmopolitan spaces being melting pots has been challenged by the idea of cultural assimilation being a process akin to the making of salad bowl. The melting pot theory assumes that cultures mingle into each other perfectly, and in a cosmopolitan space, cultures melt into each other and lose their individuality, creating a homogeneous culture.

The introduction of Urdu as a national language was based on the assumption that Pakistan would be a melting pot where several regional cultures would melt together into one homogenised unit. On the other hand, the salad bowl theory posits that in large cities, cultures exist simultaneously, while maintaining their essential and individual identities. The nuance of Hamid’s argument for cultural diversity leading to a tolerant society lies in the salad bowl theory. The various component cultures that I see in my university classroom do not come together in a melting pot, but in a salad bowl, and that is the strength of our society.

Before I conclude, I must briefly highlight a theoretical confusion: there is a difference between culture and civilisation. It is quite common to conflate these two categories which are distinct in their essence. In simple terms, civilisation is the sum of several cultures. At a more nuanced level, culture never dies. It is something that changes or evolves but the culture of a people and place does not erode with time. Civilisation, however, disintegrates with time as historians like Arnold Toynbee and Oswald Spengler have demonstrated.

The Nile Valley civilisation, for example, long ago lost its power, and has been relegated to books of history. The multifarious cultures of the Nile Valley, meanwhile, still exist and thrive in changed circumstances. As Toynbee remarks, all societies are not civilised societies. However, I want to underscore that even primitive societies (or uncivilised societies) had their distinct culture.

Whereas colonial modernity might have impressed upon the colonised their need to be civilised and cultured in the Western sense, postcolonial scholars in particular have shown that indigenous societies had their own complex cultural and social structure in pre-colonial times. Indeed, Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s call for decolonising the mind was really a call for returning to indigenous cultures predating colonial modernity.

In the case of the subcontinent, for example, that would be a pre-British Indo-Persian ethos which had its own markers of culture. Indeed, while the Indo-Persian empire did not become a fully developed civilisation, its cultural imprint still remains in its former imperial domains.

Cultures do not exist in a vacuum. For any culture to flourish, it has to be grounded in its geographical and historical setting but must also keep evolving with the passage of time. In the South Asian context, postcolonial societies were denied the moorings of their own cultural heritage when the colonial conception of modernity was imposed on these societies. The ideological polarisation in these societies is a phenomenon that I consider to be the direct result of colonial enforcement of modernity onto the colonies.

Read also: A historian’s approach

As colonisation survives in some form today in the institutions of globalisation, it becomes important to understand that a composite, unified culture does not exist. With diaspora communities, there is always a lingering sense of an original culture that persists in its original shape. However, at the moment where ideology and modernity come in contact, I have to assert that the search for a composite national culture is really the search for additions, where various cultures in a society come together to contribute to a national culture. I will conclude by saying that there are national cultures that exist across borders.

Concluded

The writer is Professor of History at GCU, Lahore.