Jamil Naqsh’s solo exhibition at the Pontone Gallery London dismantles the perception of our past and his own

Traces of Indus Valley Civilization are not merely found in artefacts, seals, statues and angular streets of Mohenjo-Daro. In a way, the culture of five thousand years ago continues -- seen in the form of a wooden bullock cart on a dirt road or among women in interior Sindh who adorn their arms with bangles, a custom depicted in the bronze figurine from Mohenjo-Daro named the Dancing Girl.

Jamil Naqsh contests this description. For him, she was not a dancing girl nor did she have any connection with present day Sindh. One can argue with his opinion, but cannot neglect how this view introduces a new element in the art of Jamil Naqsh.

Conditioned as we are to technological inventions and their speed, many amongst us expect the artists to change their visuals and imagery with each exhibition. Some artists are not easily trapped by this. Engaged with ideas, artists take a longer time to modify their expression. And even when they do shift their practice, method or imagery, it’s not a complete detachment.

Jamil Naqsh has incorporated references from the Indus Valley Civilization, its figurines, script and views of this land in his new paintings exhibited in his solo exhibition ‘Echoes’, being held from July 27-September 2, 2018 at the Pontone Gallery London. Instead of following the found examples and familiar visuals, he interprets characters, writing, and symbolism in a personal way. Contrary to rendering the figure of the Dancing Girl in that ‘frozen’ pose, untiringly painted by Pakistani artists, he imagines her to be a living entity, made of flesh, turning and twisting. Thus, in his canvases, the girl is lying, standing, holding a small statue, or wearing two horns representing the spirit of the Indus bull. The same female, at places is disjointed, almost moving in different directions -- like the construction of bodies from Futurism.

The Dancing Girl of Indus Valley Civilization in Naqsh’s paintings is not a replica or stylised form of the famous statue. It is a figure that anyone who is familiar with the portrayal of women in Gupta, Tantric, Buddhist and Rajput art would identify with as being from this land. Voluptuous, heavy and not ashamed of her presence, not inviting an outsider’s attention, content and confident in herself; these are a few characteristics of female figures in most works from Indian history. The other dominant aspect, whether rendered or residing in our minds, is of her being dark in complexion. Interestingly the Dancing Girl is also ebony, not only due to its material (bronze) but because of racial description of original inhabitants of Indus Valley (in Aryan texts) of having dark skin, flat nose and small stature.

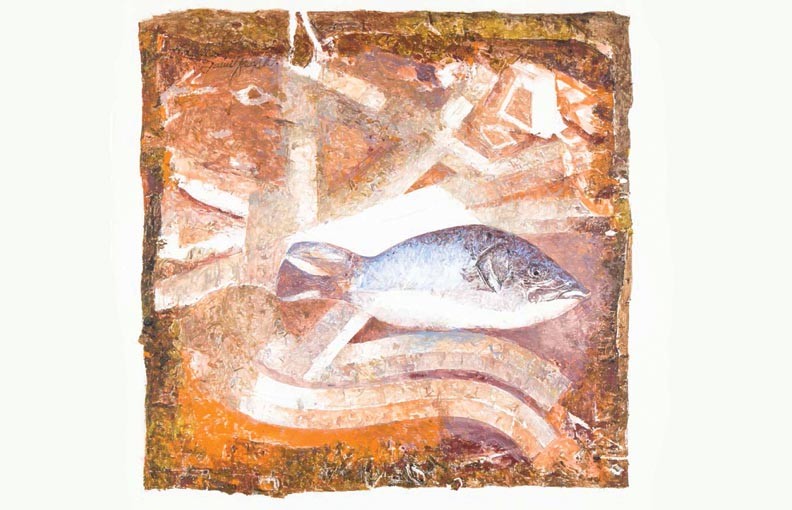

Naqsh translates this description in his mode of transcribing a living model in paint. Regardless of the fact that the figure has her origin in Sindh, Sumer or South of London, she is a symbol of the unchanging stature of a woman -- powerful and independent; a person who exists in her space, sailing through history and mystery. Naqsh infuses a metaphysical character into these women by adding horns on their heads. The horns, from the most recognisable animal of the Indus Valley Civilization, as well as fish placed next to her suggest forgotten aspects of our cultural memory in which humans and animals existed side by side in harmony. Stories, fables, epics and sacred narratives all testify the blend of mankind and animal kingdom. Buraq, fairies, mermaids, and minotaurs enter our world -- and fiction -- without anyone doubting the existing of this hybrid.

Avoiding turning his female figures into monsters, Naqsh endows them with a sensuousness that salvages them. A viewer discovers the lines of horn, traces of fish and segment of past script within the composition. Recalling his recurring imagery of a female nude (with another object: pigeon or horse), some canvases are constructed with a woman, observed with her contours, volume and weight, yet presented as if from an archaic age. It dismantles our perception about the past. Our mental picture about the people of Indus Valley Civilization is based upon our observation of figurines found from the sites. So when we imagine people from that era, they appear as a merger between a natural being and their artistic representation -- more distorted. This situation reminds one of Umberto Eco’s observation that our conception of Dark Ages depends on its portrayal in films with black & white or dominating dark shades; thus we assume there was hardly any light in that era which is impossible.

Naqsh retrieves humans from thousands of years back who look like us, probably with slightly different features and complexion, yet as living beings. In the same scheme, he converts symbols of fish, from the script, into a breathing specie. Or bull, originally from the seal, is drawn as an animal in different postures. Besides reviving rather reimagining an ancient civilization, this shift in his subject matter contributes to exploring a new language of image-making -- tilted towards abstraction. Hence, in some works, a masterly drawn figure is composed next to parts of fish, bulls, elements of landscape or sections of script.

But the most significant and surprising part of the exhibition is where the artist forgoes his own past. These enchanting, painterly, uncanny canvases are constructed as purely abstract, with segments of scripts here and there. The works confirm a basic truth about Naqsh, the painter of sensuous surfaces -- these may appear as rendering a female, a bird, an animal, but for him the abstract nature of mark-making has been an essential pursuit: the idea of picture making supersedes other obligations.

However, one must admit the power, magnificence and magic of Indus Valley Civilization. Apart from its remarkable town-planning, pottery and jewellery, it has modified the means of a painter who lives five thousand miles and five thousand years away from his origin -- of inspiration.