Churchill came to Malakand and Chakdara but he was not deputed in the specific picket now known as Churchill picket

I was in good luck when Salman Lodhi, a dear friend and colleague, was posted as deputy commissioner of Malakand a few months back. While enjoying his hospitality and the grand views from the front lawn of his official residence, I spotted a shambled grey rock structure down at the crest of the Malakand pass. Looking like a decrepit fort, abandoned and forlorn amid a maze of nondescript structures, this building begged my attention.

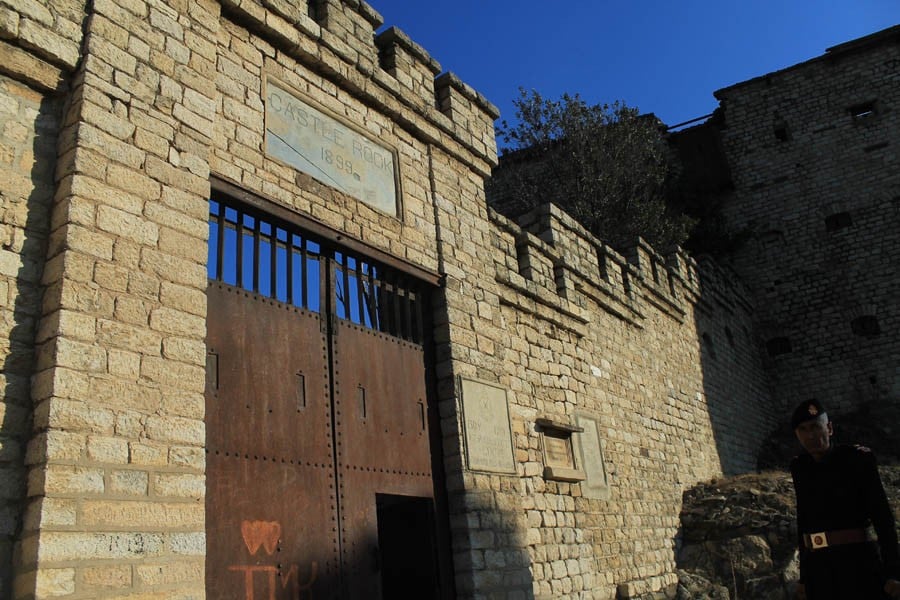

Shortly after, Salman drove us down a steep mountain road, past an army checkpoint and through a labyrinth of streets to the western side of the structure. Before us was a large iron gate worthy only of a formidable fort with some inscriptions around it: Castle Rock, built in 1899, where British officer, Major Taylor, was mortally wounded on the 26th of July 1897.

I was intrigued to explore the rest of the story.

The Malakand pass came to be of significance to the Indian government in early 1895, when a siege of the royal palace of Chitral by Umra Khan, the Nawab of Jandul, threatened a British garrison that was forced to hole up inside. Gilgit, the traditional base of all British activities in Chitral, was inaccessible at that time because the Shandur pass was snow bound. Left with no option, the government was forced to dispatch a relief column under Major General Robert Low from Peshawar to Chitral via the Lowari pass to relieve the besieged garrison. This force, known as the Chitral Relief Force, opened up the Malakand pass by fighting its way through, and established the modern road from Peshawar to Chitral, as mentioned in The Story of the Malakand Field Force by W.S. Churchill.

As a consequence it was decided that the Peshawar-Chitral road would be maintained. Churchill writes in the same book that this necessitated the establishment of a political agency in Malakand. Thus a political agency was formed the same year with Major Deane as the political agent.

Interestingly, it is for this administrative measure taken a century ago that Chitral still falls in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, despite sharing similarities with Gilgit-Baltistan in multiple respects.

Shortly after in 1897, the rise of a religious fanatic, Saidullah Khan, known as Sartor Faqir to the locals or Mad Mullah to the British, became an existential threat in Malakand. Dr. Sultan-i-Rome writes in Sartor Faqir: Life and Struggle against British Imperialism that Khan was gaining public attention even though the British knew about his preaching of a fervent religious war against the British. However, when the garrison finally realised the gravity of the situation, the tribal emotions were already aligned with the mullah’s destructive cause.

The events that followed came to be known as the ‘Malakand Rising of 1897’. Churchill writes that sentiments of religious fanaticism stoked by the insidious preaching of the mullah finally erupted on the night of July 26,and the British garrisons of Malakand and Chakdara were attacked in succession.

For a week, the mountains resonated with battle cries and gunfire. Amidst barbarism, vandalism and ferocious bloodletting was also stoic heroism. The fighting was severe, and Major Taylor of the 45th Rattray Sikhs was the first British casualty. It is this episode that is mentioned on the epitaph on Castle Rock.

The British were in better luck in Malakand for two reasons: firstly the mullah proved an utter nincompoop in terms of military stratagem; and secondly, as against Chitral of two years before, a regularly maintained road now meantMalakand was easier to resupply, due to the shorter distance from the nearest garrisons of Nowshera and Peshawar. Thus, Malakand Field Force was hurriedly tasked under General Bindon Blood to free the stricken garrisons.

After the war, the most famous treatise on these affairs of the Malakand was penned down by a young lieutenant of the British Cavalry who had later joined General Blood’s task force as a war correspondent for two newspapers. Known as Winston Spencer Churchill, in less than half a century, he became the prime minister of Britain.

Churchill’s volume praised the British soldiery. It was carefully drafted for the consumption of armchair intellectuals in England; about a frontier war in a colony he would never see. Churchill could not resist giving a mesmerising depiction of how hours before the commencement of hostilities, the locals of Malakand deliberately informed British officers of the looming battle and provided them a safe passage back to their quarters.

This was the beauty of the political system established by the British on the frontier, based on a relationship of mutual trust and respect between officers and tribal people.

Today, in Malakand, Taylor’s name has no takers while Churchill’s presence in the agency is still remembered. Commemorative plaques in an outpost called Churchill’s picket near Chakdara serve as reminders that he had been to this area. A purported claim that Churchill was "deputed" in this picket during the uprising of 1897 has no basis; as his book makes no such mention. In fact, Churchill, by his own admission reached Malakand nearly one month after the cessation of major hostilities in Malakand, and spent only one night in Chakdara. Based on a study of the various accounts of the war, it can be inferred that the same Churchill picket is most likely the signal tower, referred to in Churchill’s book.

Further, British author Isambard Wilkinson wrote an article in 2006 for the Telegraph where he placed Churchill’s life threatening encounter with tribal Pashtuns near the Churchill picket. That incident, mentioned in Churchill’s other book, My Early Life, took place not in Malakand but rather in the present day Bajaur agency.