Two artists with radically different takes on the city present a thought-provoking show at Islamabad’s Satrang Gallery

Distorted Paradigms, a two-person show by Maimoona Riaz and Farrukh Adnan presents a unique collection of striking and challenging images and perspectives reflecting landscapes, townscapes and cityscapes at Satrang Gallery in Islamabad. Not one of the places which inspired the images and views is the same today.

Photographing the urban environment inevitably has the effect of reducing volume to flat surface, and is an approach that prohibits access. In using photocopied material in her work -- whether embedding it in sculptural structures or leaving it to make its meaning alone -- Maimoona Riaz seems to be tempting an audience to regain access to the space photographed, access which the work itself then more or less consistently denies.

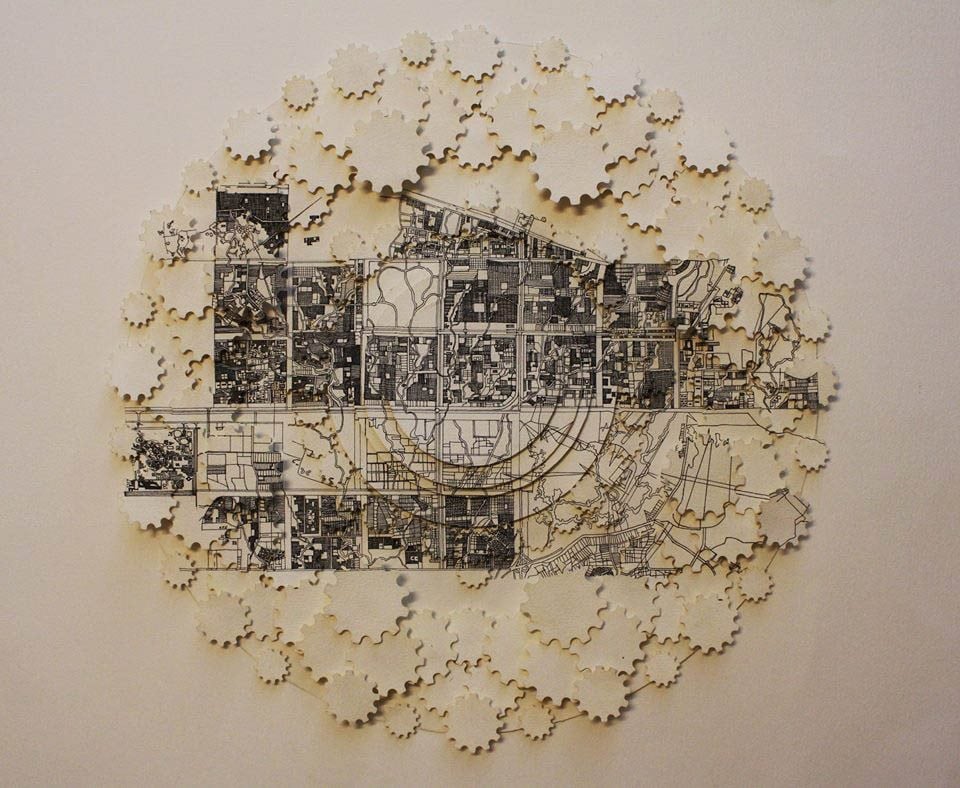

Urban landscapes, both in themselves and as framing devices, lie behind Riaz’s most consistent artistic idiom. She is best known for her ongoing series of work which presents Xeroxed and laser-drawn images of cities in oblique, inaccessible, frame-mounted spaces behind translucent glass.

‘Stumble Stones’ is a recent example of the simplicity and complexity of these works. The glass is translucent, and the image remains tantalisingly as out of focus as it is out of reach, an imaginary space dissolving real space. The work is enticing and frustrating, inviting you in while ultimately shutting you out, both from the imagined space and the real space imprisoned with it behind the glass.

These works depend for their effect on the viewer’s willingness to pick up the cues they offer to interpret the half-glimpsed, completely fictitious vistas.

In both ‘Like Clockwork’ and ‘Recurring’, the viewer is at some stage pulled up short in their approach. The works beckon you towards them, holding out the promise that this time, you will be allowed in, to wander physically as well as mentally in the imaginary perfection of Riaz’s modernist utopias. ‘Like Clockwork’, in particular plays with the possibilities of perception, offering a different view from the captured interior clearly different from the one from the window (the paper cut-out arteries signifying the urban network of roads, lanes, routes and barricades). The web-like structure pulls you towards it, and around it, the blankness of its smooth back tapering to an unforgiving point -- a palpable, physical shock. Denied entry, the viewer becomes a voyeur, the only relationship possible one of trespass, of access sought and denied.

Maimoona Riaz’s wanderings through the ‘cities’ of imagination have something in common with the long history of artistic wanderings through the modern city, from the flanerie of Flaubert and Walter Benjamin ‘botanising on the asphalt’ of 19th century Paris, to Andre Breton’s wanderings in the same city in the 1930s. ‘Wandering in the City’ might sound over-cited, but it is nevertheless how we understand such activity: walking as critique and the identification with the low and the everyday. Above all, it is a street level view as opposed to the view from the air: the view of the subject of authority. As de Certaeu argues, walking is tactical and therefore has the power to resist authority.

In these wanderings in the interstices of the modern city, Riaz is unmistakably in the orbit of cartographers. An enigmatic architectural form jutting out from a Xeroxed background recalls a number of works by Carl Andre, But whatever form it assumes, all Riaz’s work manifests a sustained and intuitive exploration of the idea of the modern city, its surfaces, forms and spaces both mental and physical. Sometimes she uses the medium for itself; sometimes she incorporates it within objects and alongside other media; and sometimes its means, and its particular visions, are merely invoked. She may alight on a specific existing urban landscape or conjure a generic, fictional space. Either way, the forms and spaces she presents are inescapably the imaginative terrain of the avant-garde, and of the urban artist of today.

Seeing the world from a high viewpoint -- from a plane, the top of a skyscraper or simply from a hilltop -- is exhilarating. It allows us, like Gulliver discovering Lilliput, to peer down on a wide view, taking in more than anyone at ground level can ever see. In art, the panorama allows both the artist and the viewer to linger over the scene as it unfolds in miniature below. The viewpoint is most often an impossible one: the artist invents a vantage point where none actually exists. It has been used in art, cinema and literature to create a sense of spectacle and to map out the world in which the narrative takes place.

This ‘impossible’ high viewpoint is a favourite device of many an artist. Farrukh Adnan’s works in this exhibition also creates a visual thrill by lifting the viewer up to a high vantage point, to look down on different slices of the world, at different periods in history. This sense of looking down on the world induces not only a sense of bewilderment, but also of emotional distance and detachment from the rest of humanity.

An expanded view also allows us to establish possession or ownership. Just as in the Bible, when the Devil takes Christ up to a very high mountain to tempt him with the prospect of "all the kingdoms of the world in their magnificence", so we see the panoramic view being used to survey estates, dominions and territories for those who command them.

Adnan loiters through the ruins of his ancestral town recording in microscopic detail with pen and ink whether on wasli or canvas, his impressions and findings as marks, dots and lines -- moments of startling transition. How far does Adnan’s view of his landscape extend? Can he see the great future metropolises? His viewpoint of the landscape could only be a mix of curiosity and vague prediction. As monumental planning cuts a swathe through the slums, Adnan wraps himself in the cloak of the flaneur, and views the town through the eyes of the detached observer, seeking to strike objectivity into the immediate view of the changing landscape, to avoid the distortion in viewpoint emotional involvement brings.

In Adnan’s drawings, distinctions between the ‘inside’ and the ‘outside’ cannot clearly be marked. Fortifications surrounded by new and more advanced architectural appendages become so complex and self-involved that they enclose nothing but the seeds of their own eventual ruin.

To sum up, in both bodies of work, the city is rewritten as a network of places that turns its back on the outside world and creates its own domains with its own set of norms, hermetically sealed edifices of artificiality, where experience is controlled. The distortion actively being controlled here is that of spatial complexity and freedom, an avoidance of any surprise that could interrupt the commodification of identity.