A pictorial and subliminal sojourn by Usman Saeed at Koel Gallery Karachi

Seeing an artist’s work and hearing him talk are two different experiences that seldom converge. Listening to Usman Saeed talk about his new body of work (from his solo exhibition Gardenfinds One, October 10-21, 2017 at Koel Gallery, Karachi), one is compelled to find the link between the eloquently uttered words and elegantly executed works.

A graduate of Royal College of Art (2006), and the National College of Arts (1999), Saeed talked about sky, cosmos, numerology, plants, garden, light, and energy, in front of works on paper created with ink and watercolour at his studio in Lahore. The works depict innumerable dots of varying size and hues, on top of each other, leading to dense layers.

As he speaks passionately, one wonders whether to hear the maker or look at his creation. Because the works of art do communicate, through senses and emotions as well as through the history of art, and context of one’s society, even if in a mute language. How does one distinguish between the artist and art? Aren’t they both one?

Not necessarily; because in most cases a work of art moves in a direction its maker had never planned. Zahoor ul Akhlaq defined art-making as a dialogue between the artist and the work. Because the artist is not conscious of his other self, hidden in the closet of psyche, that emerges and adds into his creative process, without him being aware of its presence or relevance. Images, marks, methods turn up and often astonish the maker as she sets eyes on her ‘finished’ product.

Yet, the artist always wishes to assume authorship or authority. And that power comes with words. Not unlike an orientalist who speaks on behalf of a people without a ‘developed’ tongue, the artist also takes over the role of a translator who feels obliged to enlighten a critic, a viewer, a fellow artist about his work. Usman Saeed is not an exception. Volumes upon volumes are printed with artists’ quotes about their art, their interviews where they explain their own work. Often, these texts are highly intellectual, engaging and inspiring, especially for aspiring artists or students.

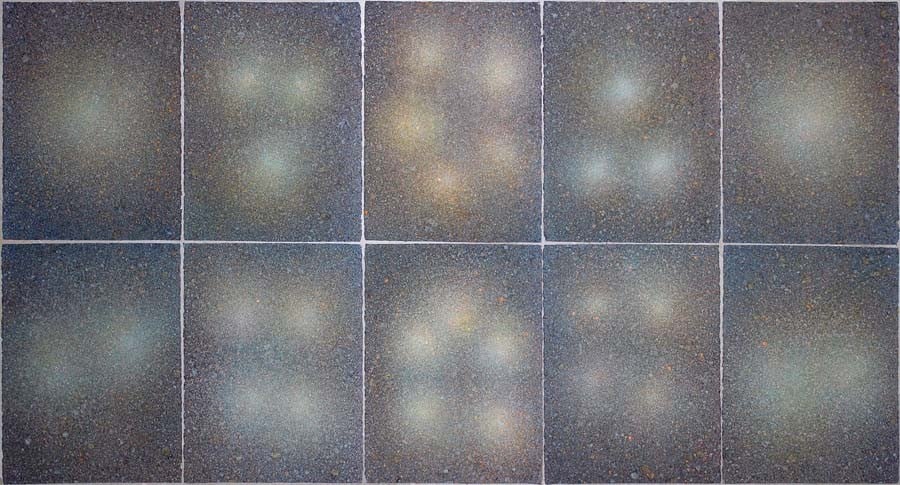

But the question remains: about the artist’s role and relevance in explaining his work. Thus looking at an art work, we need to move beyond the maker’s position. Even though one cannot deny their presence or personality. While seeing the new works of Usman Saeed, one knows about the artist’s preoccupations but more than that it is the sheer optical impact of these pieces which enthralls a spectator. On surface, you see dots and drips but the combination of these and the selection of the desired tone, determine the effect of these pieces. Saeed is showing different series, with a number of works, all about the same sensibility, but belonging to separate ideas, concerns and origins. In his work, one detects a luminous form, round or situated at centre, amid a relatively dark background, all created with innumerable dots.

Some pieces have a structured base. Thus one comes across rows of works with ascending number of circular forms, from one to two, till five and then receding in the same order. Others have a different genesis; the artist, inspired from seeing stars at night, has tried to recapture the essence of that cosmic experience. A few, owing to his involvement with vegetation, may serve as private cartography for the plants in his lawn. Saeed’s recent fondness for gardening has been transformed into his works, inspired from the position and growth of plants at his place ("This body of work is inspired by looking after my home garden and studying its biodiversity. These paintings are attempts to pay close attention to nature, using the cyclic dimensions of geometry and luminosity".)

These works (a total of 50, all titled Gardenfinds with varying numbers) offer a great deal of light and luminosity, managed by the maker. So no matter if these are derived from numerology, cosmic arrangement, layout of a lawn, the viewer has a sensory experience of emanating light. A sensation that is not possible in a static work on paper, but Saeed manages to achieve that through his skill. You are led into a pictorial and subliminal sojourn. Particularly as soon as you step into the sparse space of Koel, you are held by the light coming from these surfaces, as strong as from a celestial source.

It is difficult to decide the extent or impact of that experience. Because his work can also be read as a personal history of art. Usman Saeed did his major in miniature painting when he was a student of Fine Arts Department at NCA. Since then, being a sensitive and intelligent practitioner, he has been exploring the aesthetics of miniature painting. In the recent work, he has tried to move away from the preordained presence/practice of line much associated with the art of miniature, and opted for assemblage of dots and marks which create a strong visual sensation. For instance, in the small works about dusk, the main point of attraction is the darkness.

Shifting from line, he ventures on point, and uses it to create works with sprinkling paint on paper (sometime with the help of a toothbrush). This connects his work with the practice of making tones by putting dots in miniature painting (pardakht) and at the same time reminds one of a sprinkler in the garden used for watering plants.

In an interesting way, his professional and personal pursuits merge in his art, to make it an unusual experience both for the maker and the viewer. It is an unforgettable one because no one believed the flat papers could project light but they did -- like the flat sheet of sky.