A new documentary on Qandeel Baloch reminds us how misogyny is legitimised, strengthened and made consequence-free

Qandeel makes for difficult viewing. The documentary is 24 minutes long. It took me 53 minutes to watch it.

I had to keep pausing.

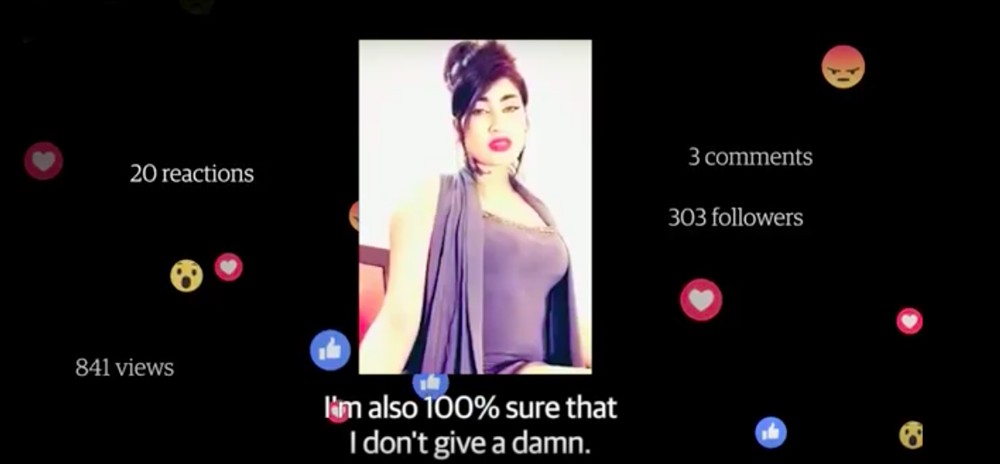

Unlike Qandeel, I couldn’t hold her gaze into the camera lens, knowing what I know now. That a girl took control of her sexual agency, that she made videos and posted them online, that this act, so commonplace in the smartphone and social media age, was so offensive that she had to be killed for it. She was as old as I am now.

Shrouded by my class privilege, armed with my feminist pride and the safety and convenience that both offer me, I am still not brave enough to listen to Qandeel’s story in one go.

Perhaps that is the purpose of the filmmakers. Like the titular character herself, the documentary does not let you look away, daring you to be as gutsy as her.

Qandeel Baloch has mystified Pakistan, in both life and death. Overnight, she went from being a punchline to a hero for some, and a cautionary tale for others. There are many parties to the story, many different enemies to choose from, but the question of who or what killed Qandeel is as complex as who she was.

The film’s framing of her life is linear; this is where Qandeel came from (small town girl, with big city girl aspirations) these were her ambitions (did not want to get married, unlike many of her ‘elite’ counterparts), this is how she was forcibly married off (before she could realise the said dreams), this is how she escaped (an abusive husband -- and built her financial independence), this was how she became a social media rock star (by being hot, pouting and showing her middle finger to anyone who criticised her for it). Pakistan was unable to handle her provocative defiance and unapologetic sexuality. She was strangled by her brother as a result.

We already know this, and Qandeel offers few, if any, new revelations. But that was never its intention. It investigates little, but it summarises well.

With the simplicity of these parameters, I feared that the filmmakers had fallen into Western trap of the proscribed accounting for how and why ‘honour killings’ are so common in us Orientals. As if one out of every three women murdered in the US are not at the hands of disgruntled lovers and husbands. As if the notion of a nation’s honour being tied to a woman’s is unique only to South Asia. As if women being unsafe in their own homes, even in their own beds, is not a global problem.

But it does not. Where directors Tazeen Bari and Saad Khan must be commended is the wide space offered to Qandeel’s family to speak about her. Her father tells us how he "impatiently" waited for Qandeel’s tv shows. Her sister fondly recalls how "beautiful" Qandeel had started looking. Her mother emphasises her desire to be educated. Within the patriarchy that created the permissive environment for her murder, Qandeel’s parents and sister are proud. This brings a complexity to their interfamily dynamics, that could have easily been subsumed by the standard ‘honour killing’ framework her story has widely come to be accepted in.

Instead, Bari and Khan remind us of the media’s role in making Qandeel so killable. With its deeply irresponsible broadcast of the details of her personal life, the media relished trading in her security for ratings. By pitting her against influential clerics -- untouchable mainstream forces -- she was rendered even more powerless. Combine that with how easy it was to caricaturise her, Qandeel became the perfect target -- as convenient to kill as if she were in the next room, sedated by pills her brother had tricked her into consuming.

The media has a responsibility; Qandeel subtly prompts us. When it introduces us to Mufti Abdul Qavi, it does so through his television appearance being broadcast live to a dhaba full of men. They hear him say that women should not defy the wishes of the men in their lives. They hear him speak of a woman’s virtue being inversely proportional to how much skin she shows.

This, the filmmakers remind us, is how misogyny is legitimised, strengthened and made consequence-free.