A group of artists refers to the vocabulary of popular culture in order to reflect on the present situation at Gandhara Art Space Karachi

We see mosques and seminaries fortified with huge walls, protected through sand bags, barricades and barbed wires. Often, they look like military structures in times of war and not a place of worship or a school. Thus, faith is unmistakably tied with technology, the biggest example of which was seen when two passenger planes were used as weapon to bring down the Twin Towers.

In an exhibition when you see a mosque dome, upside down, hollow and with some sort of hi-tech concoction (looking like a sophisticated weapon ready to be launched), you are reminded of the sermons during the Friday congregation where believers are urged to kill those belonging to a different interpretation of religion. Safdar Ali has constructed a hybrid between a dome and complex machinery, with the details of a traditional building intact and intricately painted (‘New Dream’) using wood, MDF, industrial paints and metal. The conversion of a sacred symbol into a scary device is seen again in the set of 4 digital prints, titled ‘Invaders’ in which parts of minarets are travelling around the globe like spaceships.

Safdar Ali uses the language of popular culture to denote these not-so-new realities. Part science fiction, part religious iconography, part popular pictorial expression, it makes his work exciting and meaningful.

Apart from him, other artists who participated in the group exhibition Microcosm, ‘a current survey of contemporary art curated by Adeel uz Zafar’, held from July 20-August 12, 2017 at Gandhara Art Space Karachi, also refer to the vocabulary of popular culture in order to reflect on the present situation.

With violence as its main narrative, the exhibition of contemporary art appears more like a treatise on contemporary conditions. In the works of Arsalan Nasir Hussain, Onaiz Taji, Noman Siddiqui and Haider Ali, elements of violence, division, destruction and bloodshed are visible. Arsalan Nasir Hussain has installed an interactive game (PONG) console in the gallery in which two players can compete, but the game is about point-scoring either from the Indian or Pakistani side. The familiar object, fully functional, reminds one of the conflict that is now not limited to the two states but has infiltrated our beings. Noman Siddiqui has created loaves of bread with silicon and industrial paint and has put them on different dishes (melamine, porcelain, glass, silver and bronze). Even though the execution was not too convincing, the remotely resembling meat portions (titled ‘Disparity’) indicate the inequality among social classes. They also reconnect to the memory of seeing, touching and handling raw flesh, both as a culinary practice and on sites of violence.

Majority of artists participating in the show belong to Karachi, a city that has witnessed prolonged violence. In the works of both Onaiz Taji and Haider Ali, one detects aspects of death and destruction. In his large drawings installed as two pages on the wall, besides being pages of a book, Taji has drawn innumerable tiny figures, ordinary people on a road or at an open space crowded around a corpse with congealed blood underneath. Taji’s training in miniature painting provides him the facility to capture the individuality of each person, thus giving a sense of factuality to his image. The titles, ‘17th April 2017’, and ‘25th December 2016’ affirm their actuality.

Haider Ali took pieces of found stones and printed pictures of city in varying processes of making and unmaking. A similar sensation about the city and its transformation is visible in the work of Hasan Raza in which shuttering wood with measuring scales printed on them is joined to create a skyline (‘Cityscape’), or shuttering wood, that had bark (resembling tree trunks) in the middle, forms high rise buildings on top and prints and shapes of measuring scales at the bottom -- all offering a composite view of urban environment in the work called ‘Desire’.

Like him, Haya Zaidi focuses on the city and its content. Pursuing her degree in miniature painting at NCA, Zaidi tried to translate the rubbish heaps of Karachi through the idiom of collage. For her collage was not a medium but a message, since she composed layers of images from diverse sources, without much obvious, direct or logical connection. Yet this aspect of unusual and unexpectedness became her mark and it was evident in her three works from the show, which depict the composite state of surroundings in which not only left-out stuff but living beings also indulge in each other’s life and concerns.

The difference between public and personal is realised in the works of two other artists from the show. Samya Arif employed visuals from popular culture, advertisement, cinema and famous personalities in her work, which relate to a culture that is mainly dominated by information technology, spread of images; thus, adopts a particular mode of living/thinking -- and thinging.

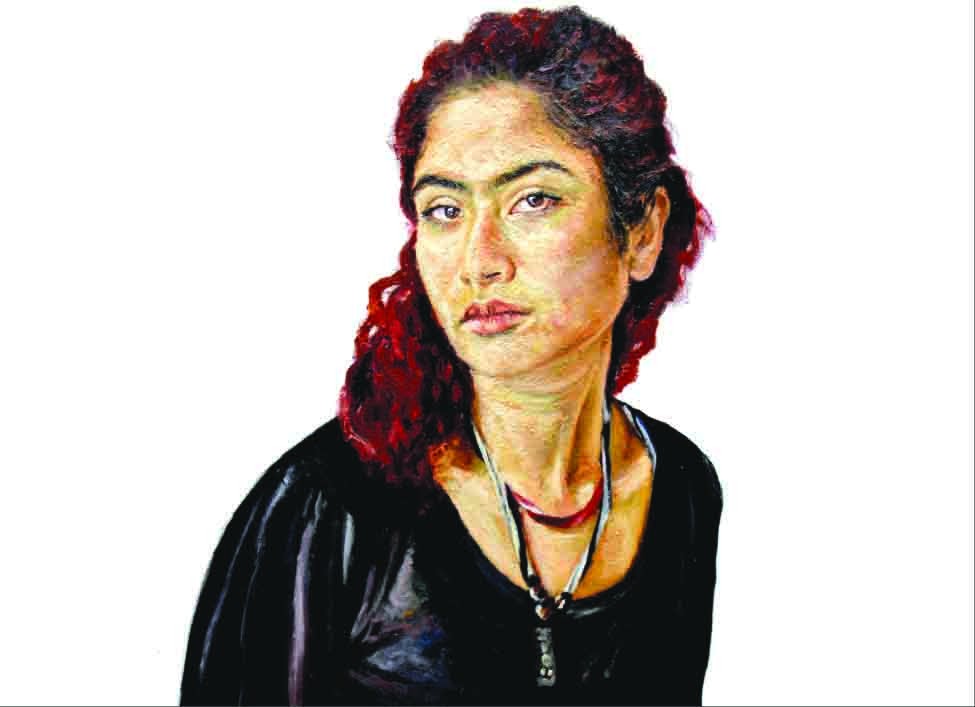

Amna Rahman on the other hand focuses on the personal and private, by painting portraits of women in her immediate circle, mostly her friends from NCA. Rahman’s mastery in rendering the detail of faces and bodies turned these beings as emblems of a very intimate world in which an outsider is not allowed or welcome. Rahman, through a simple magic of her brush, vision and craft, transforms familiar people into haunting individuals, characters who communicate our hidden sentiments to us. Her work is a means to bring personal and public together, yet refraining from a predictable course.

The bridge between personal and public, between private and shared, between inner and outer and between art and reality was grasped in a most convincing and poetic manner in the multimedia video installation of Sufyan Baig. An ordinary wooden chair was placed facing the video projection of another similar chair from another site/time. The work investigates and invokes many concerns, mainly about the realities on multiple levels -- whether the chair in wood was real or was it the one in video projection? We pass by similar sort of cheap pieces of furniture every day without taking much notice, but only when it is included in the artwork does it become another reality, more lasting, engaging and interesting -- like the exhibition Microcosm.