The Rewaj Act and other administrative arrangements warrant a debate to ensure smooth Fata transition

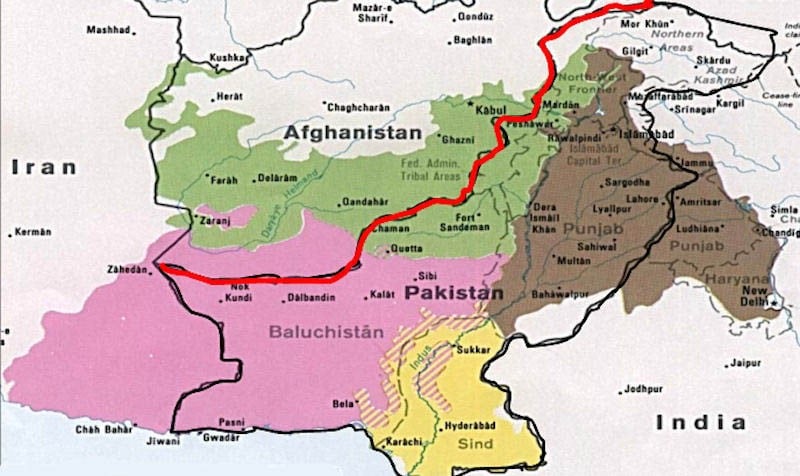

Fata’s transition seems to have come to a stalemate as vested interests are in a tug-of-war. The Rewaj Act 2017 has been presented in the National Assembly amidst much controversy.

The prime minister’s committee on Fata reforms has come up with a comprehensive report after intensive consultations. All the political parties have unanimously supported the merger except JUI-F and PkMAP.

While the debate should ideally have been on the legal and administrative aspects of the transition, proponents on both sides spent considerable energy arguing about the viability of the Rewaj Act. Neither any point of law or FCR, nor the modalities of Rewaj Act featured in the discussed.

After going through the arguments of the anti-merger camp, one doesn’t find any substance. To sum it up: ethnic, linguistic and cultural affinity; geographical contiguity, joint urban bases and administrative inter-dependence leave no other option except merger of Fata into KP.

As far as the protection of certain values and resources is concerned, the administrative modalities can be worked out. However, if referendum is agreed upon, there is no harm in it unless it is guaranteed that the same be impartial and objective.

To ensure a smooth transition, a debate on the Rewaj Act and other administrative arrangements is necessary. The Rewaj Act 2017 was conceived by the Prime Minister’s Committee, keeping in view that the traditional and time-tested mode of conflict resolution was the jirga and the fact that enforcing modern laws abruptly might disrupt the dispute resolution mechanism. Therefore, the Rewaj Act 2017 was for the transition phase for extension of the writ of the judiciary.

The Act begins with a preamble for the provision of "administrative justice, maintenance of peace and good governance", which sounds quite good provided the clauses of the act effectively fulfill these objectives. To begin with, it must be clarified that the Act is not some defined set of laws with clear procedure and exact penalties/amends in proportion to the crime/damage: Civil and criminal cases are decided on by a council of elders unanimously, which has proved to be an efficient means of dispute resolution.

However, after extension of the state laws and fundamental rights, the council of elders, too, is legally to take care of the parameters as enshrined in the laws.

Judicial powers hitherto vested with the political agent have been transferred to judges. Section-7 lays down the procedure for civil reference to the court. The same procedure/powers with definite timelines earlier administered by the political agent have now been invested with the judges. Any party to a civil dispute may make an application to the court for a decision in accordance with the Rewaj. Subsequently, the judge will nominate a council of elders and the council of elders will submit their recommendations to the judge as per Rewaj.

The judge can refer the case back, if any question of law is involved. If clear, the judge will pass the decree within seven days starting from receipt of the decision, except when the findings are not unanimous. In case a decision of the elders is not unanimous, the same will be referred back for review or the council may be reconstituted but only once.

The Rewaj Act leaves some vague areas in the dispute resolution of civil cases. What if the decision of the council of elders is in contradiction to law and the same being identified by the judge is referred back?

There is usually no absolute unanimity if we look at how jirgas have been making decisions. What if a member or a few members don’t agree to a decision for any reason? The point is if the council’s decision is in contravention of law or if there is no unanimity in the council’s decision, will it not delay and hamper the dispensation of justice?

Once the Rewaj Act is operationalised, complications are likely. The same decision-making procedure has also been proposed for criminal cases -- these are more prone to legal complications and human rights issues.

We are confusing the formal and informal mode of justice. Alternate Dispute Resolution (ADR) or jirga has never been the task for judges. Assigning ADR under Rewaj to the judges is bound to fail. Conducting arbitration and dealing with the parties and elders is not their cup of tea, rather magistrates are trained and placed at a position to administer ADR.

Perhaps, the anti-political administration rhetoric led them to decide in haste hence investing the judicial officers with ADR. A political agent or deputy commissioner should not hold judicial powers, yet the Rewaj and ADR as necessitated in Fata’s case is not inherently a judicial task. A magistrate is well-placed to administer ADR, select elders and is aware of the community’s pulse to manage bottlenecks. Hence, the pivot for Rewaj Act/jirga/ADR should be the magistrate and not a judge.

However, once the council of elders reaches a decision, the same may be submitted for the judicial officer’s approval through the magistrate. Even in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the ADR has been introduced but managed by police which again is not a relevant department. The assistant commissioner should be managing the dispute resolution committees at the district level, not the SHOs.

Section-12 calls for removal of structures and encroachments using ‘strong’ words. The clause seems a bit irrelevant in the Rewaj Act. Rather than inserting this clause, it would have been sufficient to extend the Land Acquisition Act 1894, which would serve the same purpose. The schedule contains a long list of laws that will be extended to Fata. Consequently, all the relevant departments under these laws would form their field formations for execution of the laws, which is a gigantic task and necessitate administrative efficiency.

Another law that is conspicuous by its absence is the police law. The judicial powers have been taken from the magistrate/PA but the policing powers are still with the magistrate who also is commandant of the levies force (a non-specialised cadre meant for general patrolling and arrest etc). There is no functional specialisation, and especially concerning is the absence of investigation skills which forms the basis of criminal justice system. Prosecutors will be there but who will support them in investigation? Levy personnel are trained in some basics for a few months, while their supporting law enforcement system, the ‘khasadars’ have lost all relevance.

The same goes for ‘Malakis’ who will lose relevance after the local bodies elections. The elected councilors may be named ‘Malaks’. The local bodies elections should precede the general elections so as to provide leadership for the provincial and national assemblies.

The government must not go back on its promise of reforming Fata on any pretext. Irrespective of the anti-pro merger debate, it must be realised that Fata has suffered immensely and we must be grateful to the people of Fata for their patriotism and sacrifices. The state must not lose this chance to make it up to Fata.