What makes the movement a subject of serious historical inquiry

Let me admit, at the very outset of this column, a mistake I made which is profoundly regretted. Thanks are due to Amarjit Chandan, an eminent laureate, who pointed out that Bankay Dayal and not Prabh Dayal composed Pagri Sambhal O Jatta.

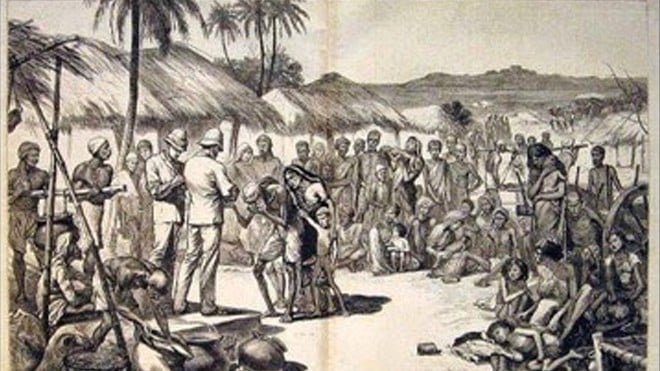

Having set that very important fact right, let’s get on with our analysis of what I will prefer calling an act of defiance and not revolutionary movement or even rebellion. This defiance was articulated in response to the British bid to order the lives of the peasantry according to the former’s will and volition. Keeping in mind the way the colonisation officers subjected every tiny detail of the subjects’ daily life to their watchful and intruding gaze, such an act of defiance was a natural corollary.

In the concluding lines of the last column, I gave certain reasons for the show of defiance by the peasantry of Chenab Colony. However in the following lines, the administrative failure, corruption and uncalled for and (mis)timed legislation are highlighted as the main causes for the unrest that exposed the British to the valour of Punjabi peasants.

Moreover, 1906 was not an opportune year for the promulgation of the Colonisation Bill. Discontent over maladministration in the Chenab Colony, brewing up since 1900, had come to a boil. The colonists were petrified over ‘the extra-legal’ fine system that had cost them an exorbitant sum of Rs300,000 in penalties. The rampant corruption among the lower officials was the most crucial factor in causing alienation among the peasants.

Gerald Barrier maintains that "the cumbersome system of assessment and records in the colony necessitated the maintenance of a large staff of Punjabi officers, whose pay, position, training and traditions, were such that they were practically certain to make the greatest possible use of any opportunities they may have for extorting bribes."

The fine system offered such an opportunity. Indian officials forced many colonists to pay bribes for petty offences. Besides, the insistence upon cleanliness and sanitation opened up additional paths for corruption.

It is underlined here that corruption in the revenue department had its roots in the colonial era. An equally important aspect is the reaction that it generated in the first decade of the twentieth century. From 1903 onwards, the situation in the Chenab Colony was continually degenerating. The plight of the colonists was so deplorable that it defies description.

The economic pressure had reached breaking point by 1906. Many colonists had lost their land because they could not prove their residency status; hence, they were exposed to a sense of sheer insecurity. Crop failure was the final blow. The boll worm destroyed the cotton crops in 1905 and 1906, which was the chief source of surplus value for landowners in the colony areas.

Read also: Pagri Sambhal O Jatta

Ironically, the Punjab government turned a blind eye towards these factors, presumably because of its well-entrenched belief that it knew what was best for rural Punjabis. The men responsible for this soaring unrest among the rural folks were Denzil Ibbetson, James Wilson, and Charles Rivaz, were once very popular administrators who commanded great respect. They were, however, vilified due to this Colonisation Bill. They were conceived of as patriarchal defenders of the cultivating class. In that particular event, they proved to be colonial administrators alienated from the popular local sentiment in their subject colony.

By coincidence, the Punjab government announced in November 1906, a drastic increase in the occupier rate -- the charge paid by the colonists on their use of canal water -- on the Bari Doab Canal running through the districts of Amritsar, Gurdaspur, and Lahore. It is important to mention here that water rates were kept lower in these districts than in the West Punjab because the government hoped that a policy of leniency would ensure the loyalty of the Sikh Jats who supplied sizable number of recruits to the British Army.

The districts mentioned above, watered by the Bari Doab Canal, were the heartland of the Majha area, the chief recruiting terrain for Sikh soldiers. However, in 1906, the Irrigation Department did not see any sound and rational reason for this sacrifice of revenue, and convinced Lord Curzon, the Viceroy of India, that the Punjab must raise its rates. The irrigation official deputed by the government of the Punjab to look into the matter suggested the same. Therefore, a sharp increase was announced in the winter of 1906. The enhancements averaged 25 per cent on cash crops such as sugarcane, and on vegetable gardens bordering the urban areas were as high as 50 per cent.

This led to a revolt on the part of the rural Jat peasantry, who rallied behind the anthem of Pagri Sambhal O Jatta.

What is remarkable about this movement is that it did not have any particular religious colouring. It was a unifying force for peasants to rise above religious differences. The power of this movement’s central image of the turban, the dominant symbol of the hard-working Punjabi rural peasant, was manifested in the rise of the Zamindar newspaper being recognised as the face of journalism in the Punjab. It was through its ownership of this movement that the newspaper gained widespread popularity through its sensational journalistic sensibility. Zamindar became a part of several pieces of popular literature in the Punjab where the symbol of the Jat and his turban were turned into archetypes for the Punjabi.

In addition to all these factors, the fact that makes the movement of Pagri Sambhal O Jatta a subject of serious historical inquiry is that it was mismanaged by the apparently successful colonial administrators. Instead of looking for a political-cum-administrative solution, they resorted to the coercive measures used by colonial administrations to supress dissent.

I undertook to write this series of columns because of the inspiration I drew from Ahmed Saleem’s talk at Faisalabad, and I am enormously grateful to him for providing a fresh thought to this important and neglected event in the modern history of the Punjab.

(Concluded)