Why the Punjabi peasantry rose up against the British

The poem entitled Pagri Sambhal O Jatta (O Jat, take care of thy turban) was recited by Prabh Dayal, a local editor, in front of 9,000 colonists (agriculturists) in Lyallpur in March 1907. That poem came to symbolise the resistance of Punjabi peasantry against the stringent measures of the British officials, enforced in the Chenab Colony.

Pagri (turban) was the key symbol in that poem which reflected self-respect for the war-like zamindars. After that meeting, the zamindars embarked on a collision course against the British administration, which had nursed the idea of disciplining its subjects (zamindars/peasants) from Chenab Colony. The contentious measure which is the focus of our study is the colonists’ bid to discipline their subjects and the sharp reaction that it evoked is the theme of today’s column.

The inspiration to write on this topic came from Ahmed Saleem’s talk at Sulaikh Mela at Faisalabad. However, before coming to the central theme, it will be appropriate to furnish its background.

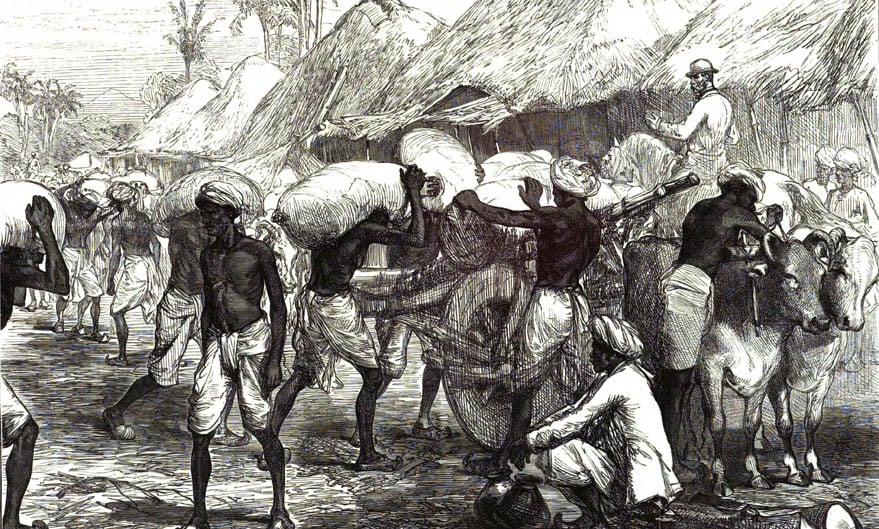

Canal colonisation in the 1860s and 1870s brought about a qualitative change in the lives of Punjabi people. As discussed in the previous columns, the economic development affected the social mobility that conjured up rural bourgeoisie comprising peasant proprietors. Land became private property with its commercial worth substantially enhanced. In that changed scenario, money lenders (Khatri banias) appeared to be the biggest beneficiary. The dire consequences ensued for the peasantry like big swathes of land began to change hands.

Read also: Reform movements and colonial state -- I

Quoting from one of previous columns would not be out of place here. "Peasants and many landowners would leave their land as collateral with the Khatri banias against the money they borrowed for everyday problems like birth, travel, marriage, and death. Since interest on the original borrowing kept compounding exponentially, eventually the original landowner was forced to forfeit his right to his land, and it would become the possession of the Khatri moneylender."

Thus the first paternal legislation, The Punjab Alienation of Land Act was invoked, which Gerald Barrier considered as "the greatest single piece of social engineering ever attempted in India". As a result of that legislation, the land owner surrendered his right to sell or mortgage his land without the prior approval of the District Officer. Hence, British paternalism came into play to safeguard the land owners (also read as agriculturalists) from the financially astute bania class.

Later on, several legislative measures were enacted to ensure that the protective shield around the Punjabi agriculturists remained firmly in place. The Punjab Pre-Emption Act, the Court of Wards Act, and the Agricultural Debt Limitation Act exemplified at best the paternalistic attitude of the British officials towards the agricultural folks.

However, the paternalistic measure which evoked quite a volatile reaction with a lasting impact was an amendment to the 1893 Punjab Colonisation of Land Act which would extend the role of the government in the daily life of the Chenab canal colony. A brief introduction to the Chenab Colony will help us put things in perspective.

Read also: Pagri Sambhal O Jatta -- II

The Chenab Colony began in 1887 when the Chenab River’s water was diverted into a system of perennial canals and resultantly the barren wasteland of central Punjab was turned into fertile farmland. The British made an investment worth Rs30,000,000 on that project for three reasons: (a) Additional revenue generation which would add to the provincial budget; (b) The colonisation of the canal area would relieve the acute population pressure on districts like Jullundur, Hoshiarpur, Sialkot, Amritsar, and Lahore; (c) It would serve as a model farm for the rest of the Punjab. Healthy agricultural communities ‘of the best Punjab type’ would be set up and kept under constant supervision.

Thus other Punjabis would get to know how proper sanitation, careful economic planning and cooperation with the government could lead to a higher living standard.

The first two official aspirations were fulfilled in due course. By 1907, it had proven to be a financial success. Not only the capital outlay had been repaid, but the government received over Rs700, 000 annually as net profit from water charges and land revenue. The government had distributed over 2,000,000 acres of cultivable land to the zamindars from the crowded districts.

What is important to note here is the way the District Officers chose the new settlers. Their ability as agriculturists, their family associations, and their ‘proven’ loyalty to the British were the key criteria. The colonisation officer in charge of the colony divided the settlers on the basis of the district, caste, and religion into small administrative units known as chaks.

In each chak, the arrangements for sanitation and orderly bazars had been made and it was carefully demarcated into agricultural zones, townships, and village greens. Each villager got one square of land, and also a plot for a house and stable. He was required to build a house, to dispose of the manure, and to build a wall around his animal yard.

Unlike other projects where the colonists were permitted to purchase proprietary rights of waste land for a nominal price, in the Chenab Colony, settlers were granted only occupancy rights, not full title to their property. Thus they were crown tenants holding their grants as long as they paid revenue and fulfilled the conditions laid down at the initiation of the grant. Peasant grantees, for example, had to live on their land, cut wood from specified areas, maintain a clean compound, and make arrangement for the sanitary disposal of night soil.

The Colonisation Officer and his subordinate local staff supervised all the details of colony life in order to ensure that each colonist fulfilled his conditions, making the officer into a dictator. His word was final in all disputes over revenue or conditions, because civil courts were considered barred from intervening in government-tenant relations. The officer also interfered in the social affairs of the colonists.

These were, according to my understanding, the reasons that the Punjabi peasantry rose up in virtual revolt against the British. Having said that, the plague, crop failure and phenomenal increase in the water rates indeed acted as catalysts in the explosive situation that Punjab witnessed in 1907. However, the stringent regulatory mechanism of the British provided the decisive cause for commotion.

(to be continued)