A fresh analytical gaze on their adversarial relationship

Ahmed Salim’s statement was loaded. Being his co-panellist at the Punjab Sulaikh Mela in Faisalabad a couple of weeks back, I was a bit taken aback when he made an assertion about the revolutionary character of some Punjabi movements. The movements in question were the Nirankari and the Namdhari movements of the 19th century whereas Pagri Sambhal o Jatta sprang up in the early twentieth century (in 1907 to be exact). Ghadar Movement and the heroics performed by Bhagat Singh and his peers were mentioned too.

Of course all of the above mentioned movements but Nirankaris were violent, quintessentially anti-colonial and rooted in the Sikh socio-religious ethos. Nirankaris were not violent but they will be mentioned in more detail in the next section of the column. Ahmed Salim hailed the proto-revolutionary nature of first three of these movements much before the outbreak of Bolshevik Revolution in Russia (in 1917) which evoked quite a lively debate.

On the contrary, the Ghadar Movement undoubtedly drew inspiration from the Bolsheviks.

Besides, these movements were shorn off their religious character and were represented as secular in their composition and intent. As a student of history, I was quite uncomfortable with such a broad sweep of statement. Ahmed Salim’s infatuation with Punjab and the enormity of his knowledge about its history and literature is well-known. His exposure and erudition on various themes on the Punjab make him a unique and incredibly prolific scholar. In him, I felt, as if poetic imagination of a laureate and penchant of dealing with facts typical of a historian were engaged in a tussle, one trying to overpower the other, and eventually the former having the last laugh.

More importantly, what is warranted here is a fresh analytical gaze to be cast on the adversarial relationship of these movements with the colonial state. Before spelling out the nature of that relationship, it is pertinent to see the springing up of these movements in a historical perspective.

Read also: Pagri Sambhal O Jatta

Both Nirankari and Namdhari movements were launched in response to the colonial state and the latter’s avowed support to the Christian missionaries who were overtly and aggressively at work to proselytise. Nirankari, a movement to purify Sikhs, was founded by Baba Dayal Das (1783-1855), a Malhotra Khatri from Peshawar who later on moved to Rawalpindi and made it the headquarter of the movement. Disgruntled over the decadence of Sikhism, filled with falsehood, superstition and error, he called for the return of Sikhism to its origins and emphasised the worship of God as nirankar (formless).

Briefly put; it was a protest movement among the Sikhs, which reinforced the purity of the days of Guru Nanak that the Sikh faith had ostensibly lost. Segregation of Sikhs from Hindus was emphatically professed, Brahmins condemned and the status of women was raised. Importantly, Nirankaris did not clash with or oppose the British, but took advantage of the freedom brought about by the British rule which allowed them to steadily grow and eventually become a permanent sect of Sikh mat.

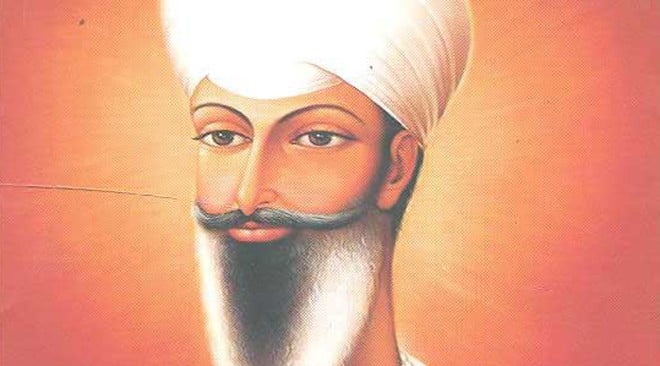

Now we should turn to the more important reform movement Namdharis (they were referred as Kukas too), founded by Baba Ram Singh (1816-1885) who was born to a poor carpenter’s family in the village of Bhaini Arayian in Ludhiana district. He was 20 when he joined Ranjit Singh’s army in 1836. Four years later, he became a disciple of Balak Singh of Hazru in Campbellpur (present day Attock).

Balak Singh was accepted by many as a reincarnation of Guru Gobind Singh which was the fundamental difference between Nirankaris and Namdharis. A little before his death, Balak Singh chose Ram Singh as his successor.

In 1857, Ram Singh inaugurated the Namdhari movement with a set of rituals modelled after Guru Gobind Singh’s founding of Khalsa. He used recitation of gurbani (hymns from the Granth Sahib), ardas (Sikh prayer), a flag, and baptism for entry into the new community. Every baptised Sikh was supposed to wear the five symbols with the exception of the kirpan which was not allowed under the British rule. Instead, they were asked to keep lathi (bamboo staff). They wore white clothes and carried a rosary to set themselves apart from other sects.

Rest of the code of edicts was almost the same as that of Nirankaris. The worship of gods, goddesses, idols, graves, trees and snakes was strictly forbidden. Popular saints were rejected and so were Brahmins, Sodhis and Bedis. A degree of equality was granted to women. They were allowed to remarry if widowed; dowries were discouraged and child marriage forbidden. Namdharis were asked to abstain from drinking, stealing, adultery, falsehood, slandering, back-biting and cheating. Since the protection of cattle was one of the most ardently held values, consumption of beef was prohibited.

In fact, slaughter of animals and the martial spirit instilled among Namdharis through the inspiration drawn from the figure of Guru Gobind Singh brought them on a warring path with the British. Namdharis resorted to open confrontation after 1871 when a small band attacked a Muslim slaughter-house in Amritsar. A month later, a second attack took place in Raikot, Ludhiana. The situation came to a head when, in a Muslim state of Malerkotla, they seized weapons and were reported to have planned an uprising against the British government.

To that threat, the British reacted with speed and viciousness. Deputy Commissioner, Ludhiana, Mr L. Cowan arrested and subsequently executed 65 Namdharis on July 16 and 17, 1872.

What is noteworthy here is the puritanical streak among the Sikhs which came as a response to proselytising campaign by the Capuchins, Presbyterians and evangelical missionaries. But what is not adequately studied is the role of a modern state and its regulatory mechanism which, as a consequence, left little space for individuals and communities to order their respective lives as they willed.

The British government’s bid to re-define the respective identities of the subject communities and coaxing them to emulate the British way of life evoked a sharp reaction against the colonial state. The most fundamental cause for pagri Sambhal o Jatta was the technologies of colonial control employed by the British, which will be dealt with in the forthcoming column.