On films that help become one with the other and let them into our hearts

Much of twentieth century scholarship in Humanities in developed academia either justified the creation of the other using clumsy logic that served ‘nationalist interest’ or exposed the mentality behind creating the other. This clash of sympathies -- one for the ruling class, the other for the vulnerable -- has educated a whole generation of writers and filmmakers.

Cinema, especially the popular one, is more driven towards upholding the status quo because it cannot jeopardise huge investment. Perhaps in countries where viewers are more sophisticated, one can find films where the director avoids the influence of Hollywood which excels in demeaning minorities. Anyone who has grown up watching early American silent comedies knows the caricatures the Native Americans were reduced to. They were interchanged with African Americans; then came the Chinese, the Mexicans, the Germans, the Japanese, the Russians, and finally the Arabs conflated with Muslims.

Racist projections were softened with humour as in the scenes when the sword-wielding Egyptian is gunned down by Harrison Ford in Raiders of the Lost Ark or the Libyans trying to steal atomic bomb secrets in Back to the Future. It doesn’t matter to the one on the receiving end whether Spielberg’s racism is manifest or latent but it’s there. Among other factors, the groundwork for the rise of someone like Donald Trump was laid by many Spielbergs at Hollywood.

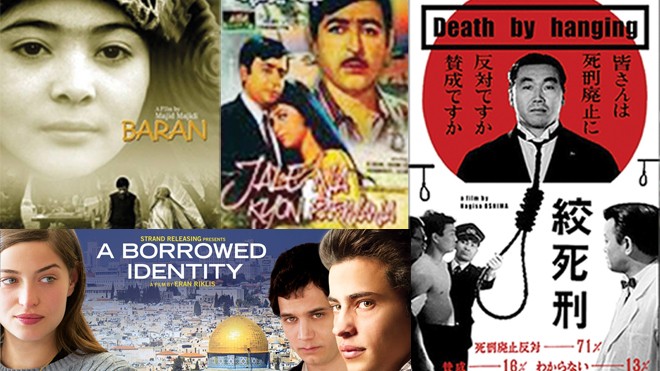

Personally, I am interested in films which explore humanity in the other, not smother it. Majid Majidi’s Baran is a delicate movie which revolves around construction workers, both Iranian and Afghan. They cannot work without permits. When the officials raid construction sites, the Afghan workers hide. When an older Afghan worker is injured, his brother dresses up his teenage niece as a boy; the contractor hires her reluctantly. Soon it becomes evident that she (he) cannot carry heavy weight. The protagonist, Latif, who is an Iranian laborer and serves tea is asked to carrying heavy sacks instead of her. She is given Latif’s work of serving tea and cooking. Resentful, he is often violent towards her and others. But at the height of his frustration he discovers that he is a young woman. Coupled by a feeling of love and remorse, he begins to help her family as she quits the job after an unsuccessful immigration raid.

Baran’s family intends to return to Afghanistan despite the ongoing civil war. In his desperation to raise money to give to Baran’s elder, Latif sells his identity card which he needs to work. The scene is symbolic that as long as you cling to your identity you cannot love. And love is the journey of becoming other.

Another film that is worth discussing here is from Israel: A Borrowed Identity, which centers around the physical and emotional struggles the Israeli Arabs go through regularly. The young Eyad is accepted into a prestigious Tel Aviv boarding school and negotiates love, betrayal, friendship, work in a hostile environment. There is a very brave scene when in a literature class Eyad’s teacher, with liberal pretensions, asks Eyad to participate, and when he refuses she accuses him of not having read the novel. He tells the teacher that he has read it but didn’t want to participate. But then he speaks shredding major Israeli writers, calmly explaining how their texts are permeated with the Arab other, the dangerous and uncivilized other.

Naomi, an Israeli student, and Eyad fall in love and withstand pressures from all sides. The betrayal comes when she tells him that it’s been her dream to join a particular wing of the Israeli army and if they found out about her involvement with a Palestinian, they’ll reject her. But he is also taken in by a left-leaning Israeli family, Edna and her son Jonathan, who suffers from muscular dystrophy. The two see themselves as outsiders. Eyad helps out Jonathan and vice versa. Edna and her son understand when they catch Eyad stealing Jonathan’s Israeli ID, so he can work. When Jonathan dies, Eyad tells the Muslim officials that Eyad has died instead. Edna attends the Muslim funeral of her son.

The last scene is an excellent critique of the kind of colonialism Israel has unleashed, underscoring the forced erasure of Palestinian identity and the moral death of the oppressor. Since Eyad has dropped out of school so Naomi’s parents could allow her to continue studying at the school, his own family disowns him. Eyad is driving Edna back after the funeral and is stopped at a checkpoint. He affirms to the solider that he is indeed Edna’s son. These are circumstances that are beyond Eyad’s control, and with a new Jewish mother, he has become an other to his real family and to himself.

The third film is an older masterpiece by Japanese film director and screenwriter Nagisa Oshima, Death by Hanging (1968). A Korean immigrant is hanged by the Japanese authorities for crimes of raping and killing Japanese women. When they check his heartbeat and pulse, he is not dead. This throws the priest, the magistrate, the jailor, the doctor and cops into moral and legal dilemma. Can they hang a person twice when he is unconscious? So first they have to revive him, which they do, but he cannot remember anything. So, again, should a person be hanged if he cannot remember his crime? He also cannot remember meanings attached to important words.

So the group, representing an entire system, begins reminding him his life and in the process exposes its own prejudices and stereotypes. Soon they are acting out the roles of his family and friend and even the women who were raped. In the second stage, as they literally become the other, they begin confessing their own crimes against Koreans and others with legal, religious and moral justification. The film becomes even more complex as his memory returns but that part doesn’t concern us here much except that Oshima hands over agency, voice and centre stage to the other.

This whole thought was triggered by an attempt to watch an old Urdu movie featuring Nadeem, my favorite Pakistani actor. I had always wanted to see Jale Na Kyun Parwana. The title itself is very creative in ways it uses the word jale meaning jealousy or burning (in/for/with) love. From commercial South Asian standards, this is a good film, the occasional flimsy camera work, editing, make-up and fake sets notwithstanding. Over all, the three leading characters have acted well. On the surface, it is a basic love triangle with the certainty that either Kamal or Nadeem will die. But scratch the surface, it is a complex film; without the director fully knowing it. Kamal, who lives in the then West Pakistan, is dissuaded by his mother from going to the West for vacation and work. As a compromise, he ends up in the then East Pakistan, a part of his country he knows nothing about. He enters the land as a tourist, as a voyeur, with a camera in hand at an appropriate moment. There’s a dance ceremony going on among tribal people, who are Hindu if memory serves me right, but the lead dancer is Shabnam, who we learn is Muslim but loves dancing.

It turns out all rich families know each other. Kamal and Shabnam’s fathers were close friends when they lived in Karachi. A much poorer Nadeem enters the picture and is introduced to Kamal by Shabnam. From that point on, it is a watered down version of Jules and Jim (1962). But before the plot thickens, Kamal says to his new friends something drastic -- he acknowledges that people in East Pakistan have a culture and a language of their own, and that he should try to learn it/them. That is such a unique moment in the history of Pakistani cinema and such a wasted opportunity!

The director recognises, from the vantage point of the West Pakistani elite class, that the other exists and there’s a subconscious desire to reach out. But the moment of awareness fritters away; the artist fails. The filmmaker and the lead actors didn’t realise that the two male contenders fight over the female aspect of what the culture of that land and space represent though all speak the language of the master. Shabnam suffers a tug-of-war but in the end the representative of the ruling elite wins. Nadeem takes the bullet, signaling the separation of two wings of Pakistan.

What if our artistes had guided us on how to become one with the other and let him/her into our hearts? That could’ve been a different story.