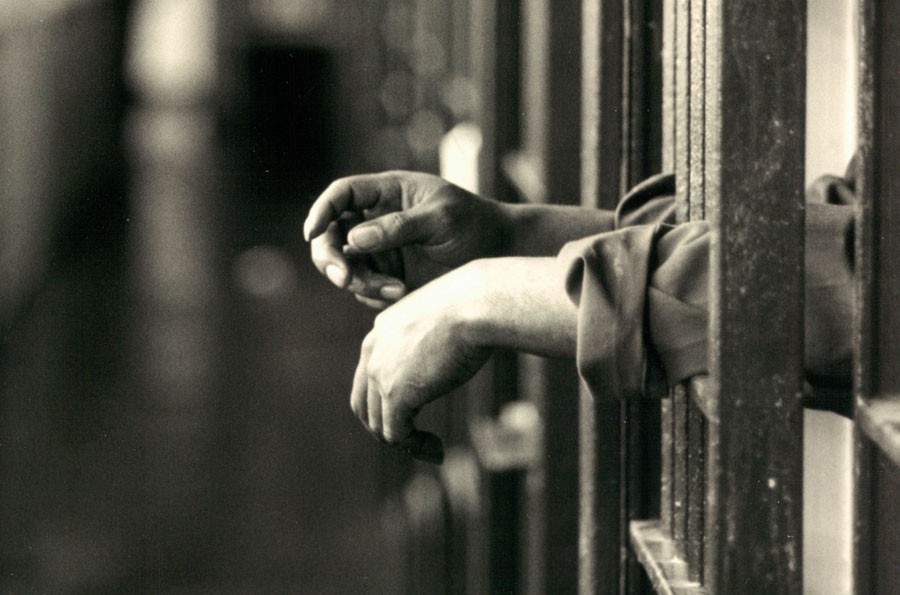

Why are 70 per cent of prisoners in Pakistan’s jails still waiting to be heard?

Sakhawat, a 43-year-old labourer from Sargodha, was first arrested in 2008. The charges against him, murder and dacoity, were severe enough, for himself to be given the death penalty. In fact Sakhawat did spend a long time, eight years to be exact, in prison. But this was neither on death row, nor serving his sentence. Sakhawat was an under trial prisoner waiting to have his case heard in lower court in Lahore.

During this time, he was almost granted bail twice. At one point his bail was dismissed on merit, meaning that his lawyer failed to provide substantial grounds for bail; at another point, in 2011, the bail request never made it to the court due to Sakhawat’s inability to pay his lawyers their fee.

The details of Sakhawat’s case and the trajectory it followed may be unique, but his status of being an under trial prisoner is fairly common. Out of the 80,169 prisoners currently in Pakistan’s jail, 70 per cent are under trial, according to Ehsan Ahmad Khokhar, a senior law adviser, during a recent press conference in Quetta.

It is not rare for an under trial prisoner to spend four to five years waiting for a sentence or bail. Since jails are too under-resourced to draw up distinctive living spaces, as prisoners wait for trials, it is understood they will be spending time with convicted, juvenile and hardened criminals. Ghazzanfar Shah, a police superintendent based in Quetta, explains that once they are sentenced, they could easily spend another four to five years waiting to have their appeal heard.

Hence, Sakhawat’s eight years in prison are no anomaly.

No one is sure about when the situation got this bad. Hammad Saeed, a Lahore-based lawyer, says a Law and Justice Commission report back from the 1960s highlights the problem of a growing number of under trial prisoners in jails across the nation, and calls for prison reforms to address the problem.

The problem may not be new, but that doesn’t imply it isn’t persistently getting worse. "Our laws are also so incredibly outdated due to our colonial hangovers and lack of will to really get back to the drawing board," says Noor Naina Zafar, a lawyer based in Karachi.

According to the latest government report issued by National Committee on Prison Reforms, the number of prisoners under trial and awaiting judgment is even larger than the one Khokhar stated: more than 75 per cent.

However, there is also the opinion that processes for under trial prisoners are being speeded up. "Following the upsurge in terrorism, particularly in the wake of the terrorist attack on the Army Public School in Peshawar, judges have faced criticisms for their failure to convict terrorists. Thereafter, the judiciary has displayed a more prosecutorial attitude with more convictions," says Zainab Malik a lawyer who works with Justice Project Pakistan, a non-profit that works with prisoners on death row.

But, Malik is quick to add, these hasty convictions are "often at the cost of procedural safeguards under the Constitution."

Most importantly, in 2011, the Pakistan People’s Party government signed a Code of Criminal Procedure (Amendment) bill that granted statutory bail to prisoners under trial if they had been charged with an offence not punishable by death and had been detained for one year. In case of an offence punishable by death, the accused should be entitled to statutory bail if the trial had not finished in two years. The law made even further concessions for women: female prisoners under trial would be eligible for statutory bail in half the time specified for male convicts. This law had previously existed on the statute books but it was revoked in the mid-90s.

While this law was welcomed, its implementation still leaves a lot to be desired.

In order for the prisoners to be let off on bail, they need to be present themselves in court but, according to the National Committee on Prison Reforms report mentioned earlier, at least 20 per cent of prisoners under trial do not manage to reach the courts due to shortage of police staff or vehicles. "This is especially a problem in Punjab (the province with the largest number of prisoners)," tells a Lahore-based police officer who wishes to remain anonymous.

He says that at court houses in both Sindh and Punjab, "you will see a couple of policemen yanking around almost a dozen prisoners, some of whom will have hearings at a different court at the same time".

Much like the report, he recommends that we need more of everything: police personnel, vans, and courts. "Only then can prisoners reach court on time to either have their trials, or even be released on bail," he says.

Explaining why the statutory bail legislation has failed to deliver justice, Zafar says that increasing courts, personnel and vans may not automatically reduce the number of under trial prisoners. "The criminal justice system’s flaws are not concentrated in any particular part of the structure, but range across the system. No one is doing their job properly."

"Lower court judges are extremely over-worked, under-paid and under-resourced. They also feel pressurised by the higher courts. In most cases they convict, and in doing so they pass on any culpability -- leaving it to the higher courts to decide," she says. She believes that if Pakistan’s trial procedures were better, if judges penalised parties more for taking too many adjournments, "the number of under trial prisoners would remarkably decrease".

Apart from the problems created by various players of the justice system, there are additional issues. These include, a backlog of cases and under-resourced and understaffed prison authorities in the face of increasing prison population. Thus, sometimes under trial prisoners are not brought to hearings because officials could not keep track of when their hearings were to be held.

Saroop Ijaz, a lawyer and Pakistan Researcher Human Rights Watch, says that typically crimes involving murder are between a complainant and the state. But in Pakistan, murder is an offence between two parties. "Often people will take their enemies to court because they know that just putting someone through the system is punishment; at other times complainants are willing to make compromises but they use the system to have the upper hand in the compromise."

His recommendation is the state should have more discretion about what can be taken to court; cases that have very little chances of conviction should not go to trial.

Another cause for the delays in trials is because it’s rare for clients and lawyers to have one-on-one meetings to discuss proceedings. Often lawyers think it’s beneath them to visit client in jail. For those who try, the procedure is very bureaucratic: lawyers have to wait for two to three hours to get about 20 minutes of time with their client and it’s common for these 20 minutes to be overlapping with the time the prisoner gets with his family.

"Jail authorities are not willing to facilitate lawyers meeting clients, so often lawyers have to meet clients on the day of their hearing," says lawyer Saeed.

It was the same case with Sakhawat. Saeed first met Sakhawat in the courtyard outside the courtroom with a horde of other prisoners, there was no privacy and the tension of the hearing was upon them.

"Often information such as the fact that the defendant may have a key witness is revealed at this moment," says Saeed. Lawyers react to this information by requesting for the hearing to be adjourned until the witness can be produced, and hence the delay.

It was the lack of witnesses that eventually allowed Sakhawat to be released on bail. The two main witnesses for Sakhawat’s murder case refused to appear in court, it was later found that one of them had absconded to Dubai. In March 2016, a judge at a lower court in Lahore granted Sakhawat bail until the witnesses could be procured. Saeed believes that it’s highly unlikely that Sakhawat’s file which is now "pending but not active" will be reopened.

However, because his record is on file, every time there is a wave of crime in the city and the police need to make arrests, he is scared they will come searching for him. For this reason he has returned to his village and Saeed has lost contact with him. Another client of his, Bilal, who was released after 4 years of being under trial, was picked up last week because of the recent crime wave in Lahore.

Technically, under trial prisoners are those waiting for their hearings in lower courts, but even stories of prisoners who have appealed against the lower court convictions are equally harrowing.

Ijaz tells of a case in which the accused, a young man of 20, was in custody for 11 years, approximately half that time was spent under trial and the remaining half waiting for his appeal hearing. "Eleven years after he was first arrested, he got a chance to have his appeal heard at the Lahore High Court. I was representing him, and I didn’t have to open my mouth to defend him," says Ijaz. It was a murder case without any witnesses or confessions, and the judge agreed the case did not have enough substance. The judge merely looked at the same documents that have been in the accused’s file for 11 years and announced that he was free to go.

"At the end, it took five minutes for the judge to set him free, but it took 11 years inside prison for those five minutes to arrive."