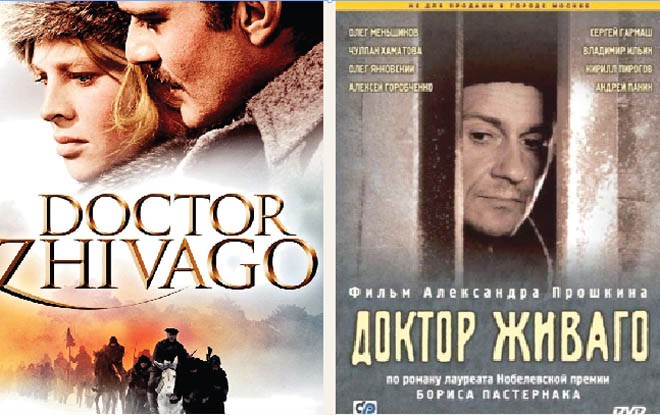

The two screen presentations of Dr Zhivago: one in 1965 and the second in 2006

As an understanding of the early 19thcentury Russia remains incomplete without reading Tolstoy’s War and Peace, a peep into the early 20th-century Eurasia requires lenses by a writer such as Boris Pasternak (1890-1960). Eurasia because his novel Dr Zhivago is not about Russia alone, it transcends the boundary between Europe and Asia i.e. the Ural Mountains. If Tolstoy was concerned mostly with the west of the Urals, Pasternak takes you to Siberia and beyond. Tolstoy brought to life the Napoleonic invasion of Russia, and Pasternak made incisions into the Russian revolution and the ensuing civil war.

Here we are more interested in two screen presentations of Dr Zhivago: First in English by the British director David Lean (1965) and the second in Russian by the Russian director Aleksandr Proshkin (2006). David Lean (1909-91) is one of the best directors in the history of cinema and before directing Dr Zhivago he had already displayed his excellence in the Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) and Lawrence of Arabia (1962), both mammoth productions of epic scale that garnered him multiple Oscar Awards. For Zhivago, he retained some of his cast and crew from Lawrence of Arabia.

Pasternak had written this novel in 1956 mostly based on his own experiences in the early decades of the 20th century. Initially, Pasternak had a soft corner for the Bolsheviks as he was an eye witness to the brutalities committed by the Tsarist Russia and the futility of throwing young men into the first world war. David Lean’s selection of Omar Sharif who was 32 then to play Zhivago -- after Peter O’ Tool’s rejection of the offer -- proved to be an apt decision.

Similarly, for screenplay Robert Bolt -- a distinguished playwright immersed in history -- converted the Pasternak novel into a highly watchable flick. His own play about Thomas More, A Man for All Seasons, and his screenplay for Lawrence of Arabia had already earned him kudos. Bolt focused on the novel’s love-triangle more than on its revolutionary details, probably because he wanted the audiences to feel the passion of love more than the pathos of social tumults. His trick worked.

It was then up to Lean who transformed the love story into a saga of immense proportions.

The French composer Maurice Jarre who had won an Oscar for his score of Lawrence of Arabia did another spectacular job with Lara’s Theme -- the leitmotif written for the film. If you are a music lover -- even if you have not seen the film -- just type Lara’s Theme in YouTube and notice the beautiful use of balalaika with orchestra. Balalaika itself remains a recurring instrument in Pasternak’s novel right from beginning when Zhivago inherits his mother’s balalaika and keeps it in all difficulties of his life. The legacy finally is carried on with Zhivago and Lara’s daughter at the end when the instrument is shown dangling from her shoulder.

Talking about Lara, the producer Carlo Ponti wanted his wife Sophia Loren to play the role but Lean did not feel she could fit into the role of a 17-year-old virgin and insisted on Julie Christie who proved that Lean was right in his judgement. Finally, Lean’s Dr Zhivago is highly indebted to the cinematographer Freddie Young -- the expert of wide-screen Cinema Scope -- who collaborated with Lean on three of his three Oscar winning films.

And now the Russian production. As we know, the Soviet government was not pleased with Pasternak and his writings. He wanted to publish his novel in the USSR but when the permission was denied he managed to smuggle the novel to Italy from where it gained access to the west and its translations in various languages became instant success. When Pasternak was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature in 1958, he was forced to decline the honour. The poor writer died in 1960 in Peredelkino, a writers’ colony near Moscow. It was only in 1988, thanks to the Glasnost (openness) policy of Gorbachev that Pasternak was rehabilitated, his novel could be published in Novi Mir -- the same magazine that refused to publish it earlier.

In 1989, Pasternak’s son could collect the Nobel Prize on his late father’s behalf and his home in Peredelkino was declared a museum. But no film or tv production was attempted in Russia till 2005.

It was Aleksandr Proshkin who took up the challenge and produced hitherto the most faithful adaptation of Pasternak’s novel. It lasts 11 episodes with over eight hours of running time and leaves David Lean’s 200-minute production at a distance. The beauty of this tv series is in its detailed depiction of almost all major characters and events in the novel.

Robert Bolt had to be economical while selecting his characters and their dialogues for obvious constraints of time. Yuriy Arabov, the Russian writer of the series had the liberty of including as much as possible in the expanded version. Be it the opening chapters of the novel in 1901 -- 16 years before the revolution -- or the discussions about land reforms in Tsarist Russia, the series provides a contextual underpinning to the novel as opposed to the rapid and at times abrupt turns in Lean’s film. The scanty presentation of pre-revolution years by Bolt deprived his screenplay of sufficient depth resulting in the somewhat uncooked characterisation.

In the novel, Lara’s character emerges much earlier and has a strong presence right from the early episodes in the series too, whereas in Lean’s film almost half of the film passes by without any meaningful portrayal of Lara. Similarly, Komorovsky of Pasternak in the Russian series is much more convincing than played by Rod Steiger. Chulpan Khamatova as Lara looks much more Russian in her manners and movements as opposed to Julie Christie who may be more beautiful but was less whimsical than Pasternak’s Lara.

Another feature that makes the Russian production a delight to watch is the originality of locations; Lean had to rely on wax and dust in the absence of bone-chilling winter in Spain where most of his movie was shot. The famous Russian winter is not easy to replicate and though Lean did a good job his lack of first hand exposure with the Russian winter can be noticed by those who have lived through freezing climate from Moscow to Siberia. Finally, the depiction of the last chapters of the novel in the Russian series is an absolute bonus because Lean’s film was much leaner in comparison and its screenplay cut short some of the most impressive and important characters in the concluding part.

If you have not watched any of them, start with the Lean one; then read the novel and notice the chopping; then get the Russian series -- with sub-titles if you don’t know the Russian language -- and dive into it for at least a week.