The traditional manner of singing the ghazal may be on its way out

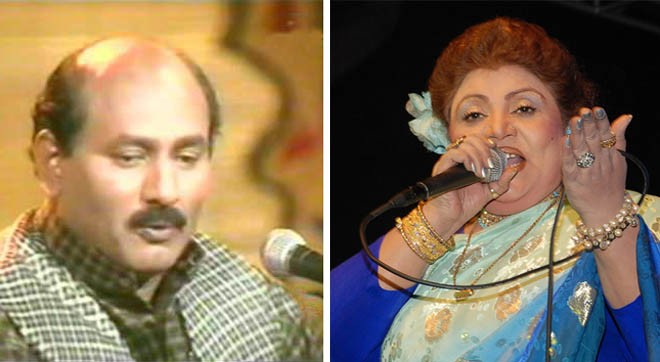

Most of the numbers at the ghazal concert that Ghulam Abbas and Tarannum Naz sang at the Alhamra last week were those made famous by their respective gurus.

In many ways, both Mehdi Hassan and Noor Jehan were very different performers and harboured a distinct style. While Noor Jehan sang with the traditional full-throated ease Mehdi Hassan developed a style that was based more on a constricted throat rendition for the enunciation of the subtlest nuance. As both were very popular and had a huge following, both styles, so to say had the approval of mass audience.

Usually in concerts, the popular taste or what the public likes or has liked often limit the vocalist to their list of preferences. As soon as the vocalist appears on stage the demand or the "farmaish" (request) as popularly known starts to be handed or shouted over for the performer to register. Some performers insist on presenting something new or what they had prepared for the occasion and then switch to obliging the requests, but it does also happen that the performer is not even given that limited freedom to play or sing what he or she intends to. Immediately, the request or farmaish becomes so overpowering that the rest of the audiences too begin to come under pressure of the overall expectation.

Since Ghulam Abbas had been tutored by Mehdi Hassan and Tarannum Naz mentored by Noor Jehan, in this concert both the performers had come with the baggage of their teachers’ repertoire; the iota of very limited freedom usually granted was hence denied to them.

The tyranny of popular taste in the arts is not always a healthy thing. The vocalist is being pressured to hold his horses, not experiment or venture forth into areas that have not been treaded before but to restrict to what the people or the audiences want. They are forced to sing their more popular numbers and that is where the case usually rests. This is not only the case for these two performers but with their gurus too the same tyranny operated. It was more the case for Mehdi Hassan than in the case for Noor Jehan. The latter rarely performed in public, and probably on very special occasions, exposing herself to live audiences much later in life. What she sang was usually film songs which made her famous across the rank and file; so whenever she performed in public she was expected to sing her film numbers and it was very rare that she sang anything besides.

Mehdi Hassan was a different type of vocalist who sang a lot in public -- both for bigger audiences in public concerts and smaller private mehfils comprising select audiences. Then he sang both the ghazal (which was primarily non-film), and film numbers; and became famous to the public at large for his film numbers. It was often seen that when he came to perform live, he requested to the audiences to allow him to sing a newly-composed ghazal. But even then, from the very beginning, his entreaty for paying attention to his new number was drowned in the farmaish of his popular film numbers. Some of his ghazals also became hugely popular after they were made part of one film or the other. But his real contribution to music was his ghazals that met with the approval of the severest critic and most demanding connoisseurs.

One also leaves such a concert with a nagging unease that the good days of the traditional ghazal gaiki are perhaps over. Ghazal as a serious pursuit of musical expression reached a new height during the course of the twentieth century as the musical forms moved away from the freedom of the abstract sur embodied in the dhrupad and kheyal to a more lyric-based rendition of the song text. Ghazal too prospered in this environment which made many believe that vocalists were just there to be handmaidens of the poets. This impression, which is widely held and strengthened by the poets themselves, is obviously a half-truth. The other half or the whole truth which may be more overbearing, is that the moment the sound came out of its syllabic mode into the domain of sur, it is the acceptance of its failure to be lacking in its full realisation. And the desire to achieve this is where music often creeps in unknowingly. All gaiks have tried to liberate the sur from the fixity of the word and those who succeeded are remembered. The rest have been forgotten as executors of tarranum.

But both the traditional ghazal as a form of literature and music shared something which is known as taghazzul. The foundation of the form of singing was laid on this aesthetic principle and then it was played out in musical form filling in the areas left exposed by the mere word. But in contemporary music, this synonymy between the two medias is being challenged by a difference in intonation, the emphaticness of the rhythmic pattern and the inundation of instruments not meant to produce melodic sound. The traditional manner of singing the ghazal, as indeed of the entire manner of intonation, which has been very peculiar to our music may be on its way out to be replaced by a new style of intonation, instrumentation and rhythmic abundance.

Probably natural sound, whether of humans or instruments too, is on its way out or is losing its monopoly over music. This will change music altogether (as if it has not already) and the ghazal in its traditional form will be remembered as having received its climax in the twentieth century.