There is much to learn about poetry from India due to the similarity of experiences

Translation, for many, is a difficult assignment, and when it comes to poetry it verges on the impossible. The value of translation especially in literature lies in making one language or society familiar to the other. Its value primarily rests on it being functional. It should not, at any time, be taken as a true representation of the literature, particularly poetry, being written in that language.

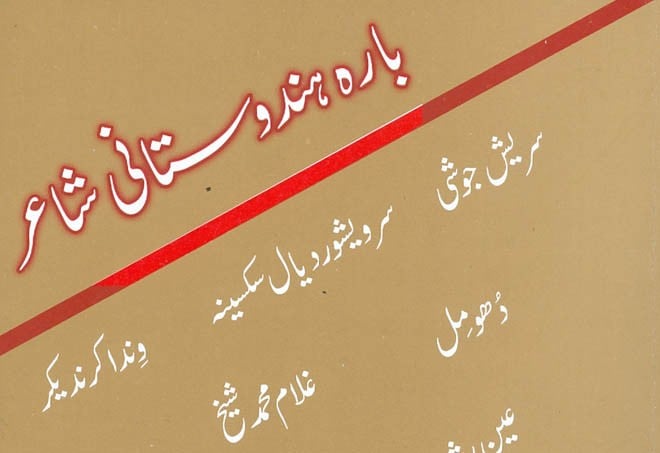

If seen within these limitations, the selection of translation of 12 Indian poets by Ajmal Kamal is a good effort because it opens the door to the poetry being written in a neighbouring country about which we do not wish to know much. There is a certain blockade when it comes to what is Indian; despite a very wide exposure to their culture, especially through films and television channels. It is taken with reservation, either as glitz not representing the real society, or as part of a disinformation campaign unleashed against others, particularly us.

But where poetry is concerned, it is something serious that should transcend crude propaganda and the one-dimensional promotion of a certain system. India is a huge country with many spoken and written languages, and to make sense of all the literature that is written there or to put it under the hammer of some assessment appears to be a very tall order.

The little that people in Pakistan know about the Indian literature is either what is written in Urdu or in English which is quite substantial, even if seen in the context of its volume. The literatures of other languages, all of them significant, is thus shielded from us due to the barriers of languages.

But there is much that can be learnt or gleaned from the poetry written in those languages, due to the similarity of experiences and the proximity of time and space. India and Pakistan have so much in common that to separate it or identify it is a losing proposition to start with.

It also appears that Ajmal Kamal, the editor has selected poets and poetry that are not conventional but has ventured forth to experiment in form and content. It has been stressed so in the small and concise comments that appear before the text and also with each poet. It may be said that these introductory notes are too brief and leave the reader curious and insatiated for more context about the poetry and the poets.

One good aspect is that some of the poems have been translated into Urdu from the original languages. But it appears that some have first been translated into Hindi and then into Urdu. The process is not very clear, whether the translations into Hindi were the proper and certified ones or whether these were translated into Hindi for the convenience of again translating them into Urdu specifically for this particular volume. Similarly many translations are from English and again it is unclear whether these were first translated into English and then into Urdu for this particular volume.

If the translations have been extant and published, they too have their own value and must have been independently assessed. But if done only for this particular volume, the assessment is doubly shrouded.

It often happens that the poems in languages are first translated into English and then translated into Urdu and this act of twice or thrice removed robs or mixes the original flavour of the poems with the flavour of each of the languages that it is processed through. With every translation something is added and something is lost that obfuscates poetry and recreates it. For example, in the case of Amrita Pritam the editor’s note says that she has also written in Hindi and these have been liberal translations of her Punjabi works. These now have been translated for this volume from Hindi into Urdu.

The five languages are Gujarati, Hindi, Marathi, Punjabi and Urdu. Suresh Joshi and Ghulam Muhammed Sheikh have been translated from Gujarati by Guresh Dumniya/ Ajmal Kamal, Sarveshwar Dayal Sakseena from Hindi by Asad Mohammad Khan, Winda Karandekar translated from English by Asad Muhammad Khan , Dhoomil translated from Hindi by Ajmal Kamal, Arun Coletkar translated from English by Ajmal Kamal, Amrita Pritam translated from Hindi by Ajmal Kamal, Rajesh Joshi translated from Hindi by Ajmal Kamal, Punch Singh translated from Hindi by Ajmal Kamal, Asad Zaidi translated from Hindi by Wali Ram Walhab and Manglesh Dabraal translated from Hindi by Ajmal Kamal. It appears that Ain Rasheed originally writes in Urdu and thus there was no translation involved.