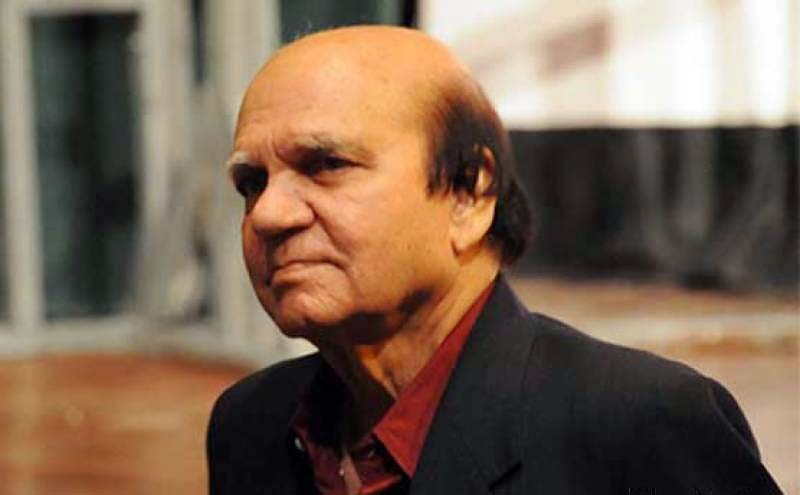

Agha Nasir’s life may well be divided into two parts -- his journey as a broadcaster who also managed the media networks, and his growth as a creative genius after he quit television and other such jobs to concentrate on writing. He eventually published many books on literature, theatre personalities and, chiefly, his beloved television. Nasir also scripted plays for TV but the compulsions of producing them on the one hand and managing the corporation on the other, left him little personal time and energy. A mild-mannered man, Nasir turned out to be a survivor. For years, television was state-controlled in Pakistan, and its contents were closely monitored. Any aberration or variation from the official version could see one out. Aslam Azhar, whose name is synonymous with Pakistan Television Corporation, is one glorious case in point: This PTV’s recognised genius was unceremoniously removed because he had suggested a few changes for greater freedom in news and views. Agha Nasir, too, had his share of woes: He was transferred to National Film Development Corporation (NAFDEC), then to Pakistan Broadcasting Corporation (PBC), and Shalimar Recording Company (SRC) and back to PTV. He survived pressures during all those years and bounced back to reclaim the top job at television every time. It was his tactfulness and low-key approach that made him indispensable. In those days, there was only one television channel. But, given the limitations, Nasir did achieve great heights. He left no room for the narrow-minded bosses to even attempt a takeover, producing plenty of quality programmes that took PTV to newer heights of excellence. Like most people, his nursery was radio that he joined after leaving university. He schooled himself in the finer aspects of broadcasting, especially the radio play and the most eagerly-awaited show, Hamid Mian Ke Haan. It was the same legacy that served him well as indeed many others when television was established. One of those rare few who were asked to join immediately, Nasir transferred the richness of the radio play to the new medium that not many were familiar with. Almost a pioneer, he soon moved into the policy-making slot and was a major contributor to the (gradual) maturation of the medium through peaceful as well as turbulent times.

One of those rare few asked to join immediately, Nasir transferred the richness of the radio play to the new medium that not many were familiar with. Almost a pioneer, he soon moved into the policy-making slot and was a major contributor to the (gradual) maturation of the medium through peaceful as well as turbulent times.

Back then, drama and music were the fortes of radio. Drama, in particular, flourished because there was no commercial compulsion which bedevilled theatre on public stage. The early days of PTV also had fewer commercial constraints, and the ratings obsession had not yet set in. Not the one to stick his neck out unnecessarily -- staying always one step behind, Agha Nasir saw from close quarters the promising careers of many being mowed down. But to survive too is an art, and he shuffled from one position to another returning to the steady ship of television. In the last few years of his life, Nasir wrote and published many books. He was indeed very prolific. Television had found its chronicler in him. He disclosed how Altaf Gauhar was able to convince President Ayub Khan about the great potential of television for propaganda. Citing examples of Abdul Gamal Nasser and other authoritarian rulers at the time when general elections were due, he swung the argument in favour of setting up TV, whereas in India television was dismissed as a luxury that could wait its turn. So, PTV was launched with the purpose of being a propaganda tool, and it was left to those running it to create some space for other creative activities. Nasir took upon himself a task which many people found very useful -- he chose to describe the motivation of a hundred poems of Faiz. It has often been asserted that there should be a link between the objective happenings and the poet’s life because that makes it easier for the reader to draw a relationship map between the creator and the created. Usually, examples of literary and artistic production in various other parts of the world, particularly the West, where it is supposed that the link between the two is less tenuous and surreptitious than it is in our literature are quoted. When

Gumshuda Log, an anthology of newspaper columns that Agha Nasir had written on the personalities he had encountered in his life, was published, there was hope that his other writings would also be printed for the invaluable information that they contained. That expectation was fulfilled with

Gulshan e Yaad. The sketches may be divided into people who were renowned like Faiz, Sadequain, Z.A. Bokhari, Khawaja Moinuddin, Saleem Ahmed; and those he had a more intimate interaction with -- such as Riaz Farshori, Muslehuddin, Athar Ali, and his own mother Ghafari Begum. Faiz Ahmad Faiz was not known to have written for stage or television, though it is generally considered that he adapted Shaukat Siddiqui’s novel

Khuda Ki Basti for TV and may have had a role to play in producing it also. But Agha Nasir added to everybody’s knowledge -- and to the fund of literature -- by including two plays of Faiz’s:

Private Secretary and

Hota Hai Shab-o- Roz. These were, according to him, written for radio but apparently produced for television in 1970. The third play, titled

Dehli Ki Aakhri Shaam, was scripted by Soofi Tabassum in which many a known actor took part.

Agha Nasir passed away on July 12, 2016.