The brilliance of vocalists like Mehdi Hassan was that even while responding to public’s evolving taste, they carefully kept classical music traditions alive

One wonders whether the youngsters listen to Mehdi Hassan. His gaiki or what he sang must be categorised as "classical" and set aside in the same manner in which the kheyal and thumri were categorised and set aside in the decade of the 1960s and 70s -- as being too arcane, inscrutable and unrelated to what was happening around us.

Though the first three decades after the creation of Pakistan did see the rise of the ghazal as a serious form of music due to a variety of reasons, the people were more tuned in to film music where they could draw a direct relationship of the composition which for them meant the bol, the situation of the film and the condition in which the actor was placed. This, an easy option of relating to some external condition or some recognisable aspect, was and has been the main reason for the instant popularity of a song or a music number. According to many, mostly lay critics it has been critical to draw linkages between the contemporary reality or happenings and the content of the song. Any less was dismissed as being too esoteric, therefore elitist; too heavy on craftsmanship and therefore formalistic; or too much in search of realisable references from the past, and hence, feudal.

The instant topicality of the numbers was seen as an operative canon. If Pakistan went to war, there had to be taraanas rousing the nation to war; if there was an atomic explosion, then there had to be songs in appreciation of the bang; and if there was corruption in the society there had to be one with profuse allusions to that. In the past couple of decades, such numbers have been aplenty, like flash in the pan they disappear with the same alacrity with which they appear and leave not a rack behind.

There is great draw in music replacing or adding to the conversations taking place on the television channels and social media. The usual topics under discussion are the conspiratorial underpinning in the instability of the country, the sex scandal of a public figure, the military political civil relationship, the rising cost of living, the corruption in society, the desire to make a quick buck and the need for religiosity in an otherwise very materially-oriented consumerist society. If there is a song depicting all of this, no matter what its quality, it adds to the gossip and tongues can wag for a week or so which is the usual duration of a popular number these days.

Globalisation, too, has changed the sonic nature of music. The growing dependence on electronic, computer-generated sounds in an area that is expanding fast in exploring non-natural sounds is appearing to be more appealing than a full-throated application of the note. Similarly, the guitar has replaced the local instruments as the ubiquitous reality of sonic imminence and that has changed the "lagao" of the sur. The guitar and the keyboard have changed our music or the intonation of the note. To be fair, more than just our music has changed; the playing of these instruments is conditioned by a culture that is hovering over us in its more internationalised expression.

Since the Second World War, as popular culture all over the world became an inviolable virtue the attention has shifted to the primacy of the lyrics. These bring a ready reference to the situation that is taking place around us and is a more direct manner of communication, though only on the surface, than the musical non-verbal expression that is always more difficult to pin-point in its definitiveness. The new forms which found favour with the urban audiences were word-centred rather than exclusively reliant on the note. Ghazal was considered a happy compromise for, as a poetical form too, it had greater links with the Central Asian and Persian literary traditions.

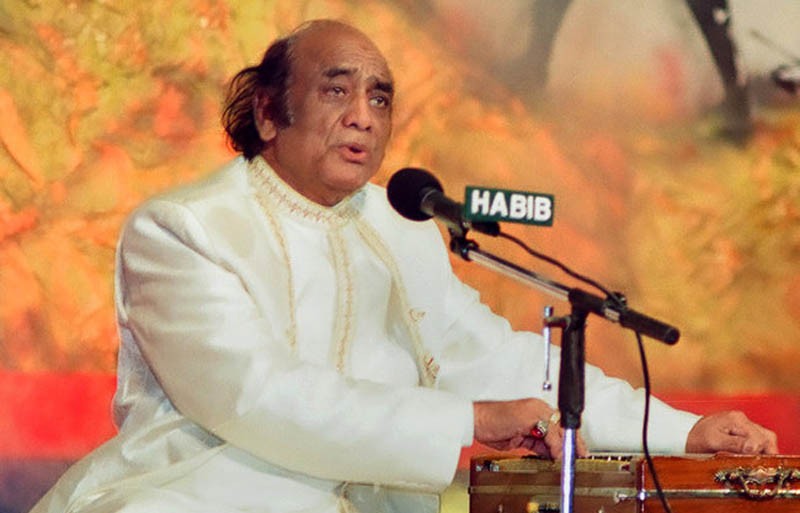

In this region what to talk of Bare Ghulam Ali Khan, Amir Khan and Fateh Ali Khan, even Mehdi Hassan is becoming more obscure by the passing minute. He, in a way, was the product of a changing musical environment himself. Very few people in Pakistan were interested in classical music in which Mehdi Hassan properly nurtured his craft. He switched to the thumri and dadra, and that too the audiences found too abstract; he further moved to the more word-centred form of the ghazal. And like others before him, Barkat Ali Khan, Mukhtar Begum and Begum Akhtar created more musical space within the restrictive constraint of the word-centred form. In Pakistan, there have been three great exponents of the ghazal gaiki, Farida Khanum, Iqbal Bano and Mehdi Hassan contributing in many similar and dissimilar styles to the evolution of ghazal gaiki in the last fifty years or so. Three other exponents of the ghazal gaiki, Ustad Barkat Ali Khan, Rafiq Ghaznavi and Muhammad Hussain Nagina had already enriched it. Actually, it was Ustad Barkat Ali Khan who brought the thumri ang of singing into the ghazal gaiki and hence started a new trend that was to characterise this form for the next many years to come. Some other names should also be mentioned in this regard: Shamshad Bai was a good ghazal singer as was Bhai Chhela. And who can forget that Pyare Sahib was held in high esteem once.

The brilliance of all these vocalists was that they kept the musical loss to the minimum retaining the richness of the thumri ang in their rendition of the kheyal. All the popular forms including the film song too developed by maintaining a strong connection with the kheyal/ thumri but it appears that the current changes or changes in the recent past have put no premium on the vital connection between the two. The singers who were trained in the classical forms and were apt to sing the kheyal and thumri then brought their musical knowledge to the singing of the ghazal. This enriched musically beyond measure the ghazal gaiki as gradually all the embellishments that were part of the thumri ang found their way into this new evolving form. The more romantic strain in our gaiki which is possibly expressed in the short behlavas, murkis and zamzamas were creatively employed in this new emerging form.