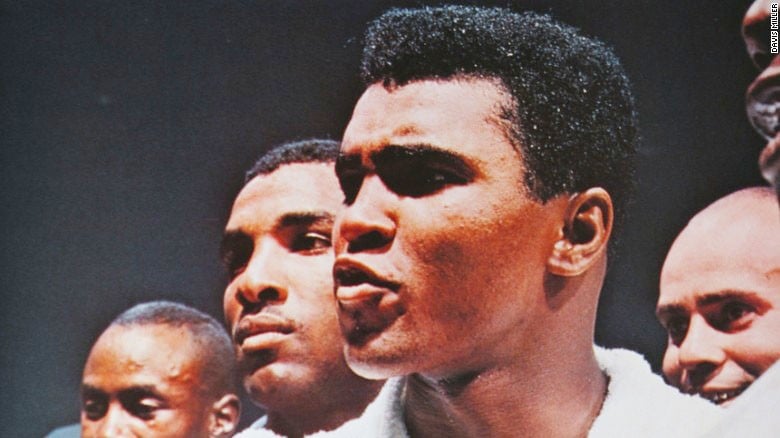

"I’m not only a fighter. I’m a poet; I’m a prophet; I’m the resurrector; I’m the savior of the boxing world. If it wasn’t for me, the game would be dead," he said. In any other sport, coming from any other sportsman, this statement would be considered showing off. However, when Muhammad Ali said it about boxing in the 1960s and 1970s, he was merely stating a fact.

Muhammad Ali is no more. For the past few years, he had been away from media limelight as Parkinson’s took hold of his body and caused irrevocable deterioration. He was not forgotten, though. The outpouring of grief at his funeral embodies just how much he was loved. Significantly, he was idol to several iconic figures in recent memory.

Born as Cassius Clay, he converted to Islam under the influence of the controversial, separatist Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad. The movement was built on an intense hatred of white people, and its leader preached that white people were devils. Ali unabashedly defended his loyalty to this movement. He insisted that his new name should be recognised and he should be called by that name, because as he said, "Clay was my slave name".

This stance was, at times, even criticised by fellow Blacks, most notably boxer Floyd Patterson who accused Ali of "disgracing the Negro race".

This belligerent defiance of societal expectations was never more evident than in Ali’s staunch refusal to be drafted in to fight the Vietnam War. His adamant denial of any duty to fight for the US forces brought punishment in the form of being stripped of his title and not being allowed to box in the prime of his career. It also made him an icon of resistance.

He was, simultaneously, a major figure in the civil rights movement led by Martin Luther King. His support of King was particularly strange because the Nation of Islam and Martin Luther were opposites of each other and criticised each other openly. It is, therefore, a testament to Ali’s commitment to his cause that while he was an unerring defender of the Nation’s exclusionist policies, he was also a vociferous supporter of King’s integrationist policies.

On television, he never appeared to be humble. He loudly proclaimed himself to be ‘The Greatest’, and against Joe Frazier in 1975, he shouted at all those who called him an ‘underdog’. He did not like being thought of as an underdog, and proved everyone wrong on many occasions.

Ali was, to me, the original rapper, who made African-American rhyme and rhythm ‘cool’. The grounds for an African-American idiom in poetry had been laid by the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s and the 1930s. Poets like Langston Hughes, though, were more refined and aware of literary sensibilities in creating poetry. Muhammad Ali the poet, like most of what he did, was organic and rooted. Being interviewed in the boxing ring, an electric Ali, in characteristic exaggeration, stated, "I’ve wrestled with alligators,/ I’ve tussled with a whale./ I done handcuffed lightning/ And thrown thunder in jail./ You know I’m bad./ Just last week, I murdered a rock,/ Injured a stone, Hospitalized a brick./ I’m so mean, I make medicine sick". This is the rhythm of modern rap, and while the rhyme might mostly amuse, it has a more serious assertion underlying it.

Muhammad Ali asserted ‘Black Pride’ every chance he got. It is not surprising that African-American sporting icons like Michael Jordan (Basketball), Mike Tyson (Boxing), and Tiger Woods (Golf) thought of him as mentor and inspiration. It was Ali who paved way for these sporting greats of the twentieth century by making it possible for athletes of colour to be recognised and treated as equals. He weakened many of the barriers that Jordan and Woods later broke. That is why his contribution to sport in general and to African-American dominance over sport particularly rises beyond any measures of quantity.

More significantly, perhaps, he inspired two of the most important leaders of our times. There is a very famous picture of an aged Nelson Mandela and an ill Muhammad Ali exchanging jabs in jest. Ali inspired the African nations which had still not won equal rights. Barack Obama, the first African-American president of the United States, paid a heartfelt tribute to Ali, and acknowledged how, while growing up, Ali’s struggle was an inspiration to him and other Black youth. Mandela and Obama achieved in politics what Ali started in the boxing ring.

He was voted the greatest sportsman of the century, a fitting tribute, because while Pele was an icon only in football, Ali’s influence reached multiple sports, and multiple nations. He was an inspiration to generations of fans, and even those of us who had never seen him fight, were moved to tears when in 1996, he lighted the Olympic torch at the Atlanta Olympics. His right hand shook, so he steadied it with his left. It was yet another act of defiance against a disease that had hosted in his body for decades.

In Harper Lee’s iconic novel To Kill a Mockingbird, the protagonist Atticus Finch delivers a potent lesson to his daughter. "Courage," he says, "is not a man with a gun in his hand." Instead, he defines courage as knowing that the odds are stacked against you and still getting up to fight. Muhammad Ali had all kinds of odds stacked against him, but he laughed at all the hurdles, and by doing so, overcame them.