Three simultaneous exhibitions in Lahore showcasing landscape painting draw attention to the genre in different ways

Landscape is back with a bang. Two exhibitions of landscape painting opened in the afternoon of April 29, 2016 -- Blossoms in Spring at Oyster Art Gallery, and Between Heaven and Earth at Taseer Art Gallery Lahore. A third one was inaugurated the very next day in the same city at Co-opera Art Gallery. Called Group Show of Watercolours, most works included landscapes, cityscapes and seascapes.

The Oyster show was crowded not just by viewers but with a plethora of paintings. A painter complained at the opening that with rapid urbanisation, his subjects were disappearing. With continuous construction, it is indeed difficult to locate a peaceful pastoral-looking spot with trees, fields, ponds, wandering animals, mud houses and occasional inhabitants.

Somehow this -- the disappearance of subjects -- was the case at the exhibition venue. The paintings were put so close to each other that it became difficult to concentrate and judge the level of observation and execution of each canvas. You could pass by stretches of surfaces, with scenes of rural Punjab, mountains from the North or boats in Karachi, without really stopping, admiring or analysing each work. Like a congested blocks of flats, where sounds of loving couples, brawling kids; radio songs and television dialogues amalgamate, the imagery of one landscape was overshadowed by that of the paintings hanging on both sides.

There is nothing ‘new’ in these landscapes, because in nature the idea of newness is different from that in a man-made world. In nature, the concept of recycling and return is more appropriate as every spring trees grow fresh flowers and leaves that wilt and fall in autumn; so a pattern is set. Thus, a canvas with a cluster of trees or spread of fields may have been painted in 2016 but there is nothing in the imagery which suggests the visual ‘belongs’ to the present; it may well be from 2001 or 1961 for that matter.

A painting with elements from nature can very well denote the period -- whether it was created after Impressionism, before Ustad Allah Bux or made in the times of Khalid Iqbal. Perhaps Khalid Iqbal is the best example in this regard because, in his canvases, one could hardly glimpse traces of modern age -- except the occasional electricity poles. Yet, his sensibility and sensitivity confirm his contemporariness. The way he constructs his surfaces with layers of paint and brush strokes make him a painter living in an age where the process of art-making is important along with the choice of subject matter or the skill of portraying it.

Iqbal’s landscapes present the way an artist discovers new possibilities in a genre that has been practiced too much and too often, and is thus exhausted. His work indicates that copying him won’t be a good course; perhaps learning from his example of extending the concept of landscape is. There have been artists who have explored the idea and genre of landscape in order to create a personal vision -- which includes both the way of seeing and the way of saying. Artists like Ijaz ul Hassan, Zubeida Javed, Ghulam Rasul and Mussarat Mirza are a few names in this regard.

The other exhibition Between Heaven and Earth was an attempt to expand the definition and notion of landscape. Interestingly, the display includes an installation made of mirrors in a cube by Faraz Aamer Khan besides showcasing views of mustard fields painted in oil by Raja Najam ul Hassan. Likewise, the show comprises of a number of graphite on paper works with delicate rendering of trees by Emaan Shaikh along with Inkjet prints made by Atif Khan which investigate the limitations of landscape.

At the Taseer Art Gallery, one sensed the urge to explore other aspects of landscape that are not about recording what the eyes see but what the mind feels and thinks about. Thus, in front of works on paper by Fraaz Aamer Khan, one could get the same sensation as in the presence of sea on a cloudless and starless night, and be reminded of the beautiful poem of Faiz where he describes the day merging into night as a long embrace. Emaan Shaikh’s small rendering of trees in black and white makes us look beyond the confines of our conditioned descriptions of trees: it attunes us to appreciate the essence of looking at the foliage or recalling the experience of seeing tree at a specific time.

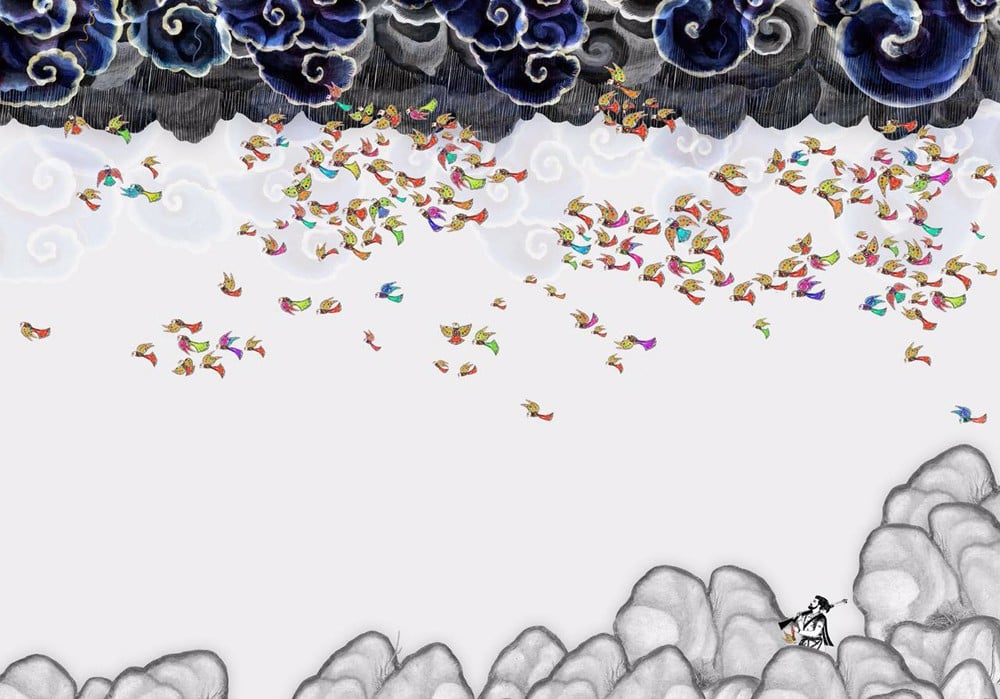

The Inkjet prints of Atif Khan present a wide, probably the widest, definition of landscape. These draw references from various sources, and what is projected is a remote idea of landscape rather than a photographic documentation of a particular place. Thus in his work, one can glimpse traces of miniature in the form of a tree, birds in a conference and clouds with bolts of lights -- all attempts to suggest that our land and landscape is beyond the limitation of time. He has introduced links and references from history of image-making and the legacy of literature, in which garden is described, or depicted, through other schemes.

If the idea of landscape is extended, and hence becomes relevant, at one art exhibition, other venues which intend to showcase landscape suggest that in the next century there may not be any open land in the world of concrete and iron but there will be landscape art. Then perhaps it might become an interesting, imaginative and innovative art form. But it isn’t so today.