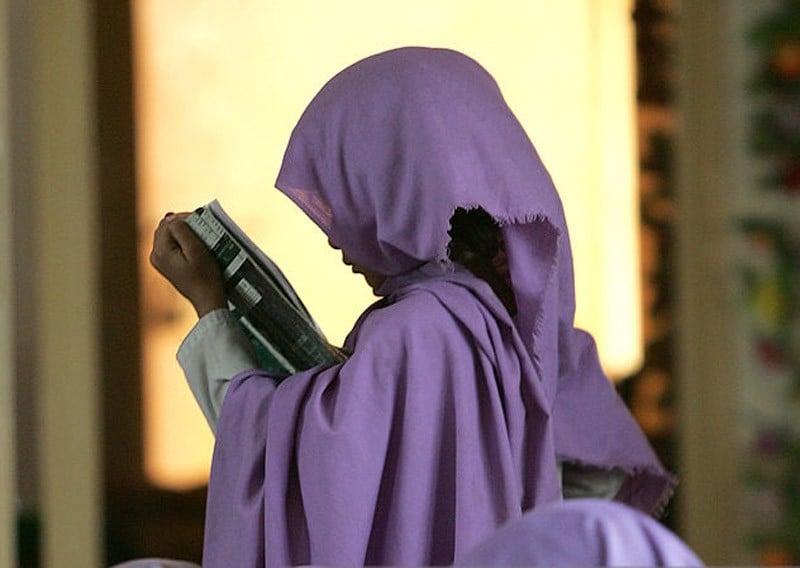

Enrolment of girls is increasing in madrassas all over the country, who are learning to become religious specialists

Muhammad Asghar, an employee at a private bank in Karachi, proudly says he has recently withdrawn his two daughters, aged 13 and 16, from a school and admitted them to a madrassa. He says a number of people in his circle of friends and family did it because all of them are not satisfied with the general state of education. "The madrassa graduates are decent citizens of high morals and ethics which is absent in others. I want to make my daughters alima".

A few decades earlier we heard little about women becoming alima (qualified religious scholars). Today, there are a number of them.

Enrolment of female students in madrassas of all sects has been expanding rapidly in the country, reveals the madrassas’ boards statistics. Even girls outnumber boys in registration for examinations at lower classes of Dars-e-Nizami -- the madrassa syllabus.

This year, 123,844 girls and 97,159 boys will sit in annual examinations of different levels of Dars-e-Nizami registered with the Wifaq ul Madaris Al-Arabia, one of the five boards representing Deobandi seminaries in Pakistan. Other four madrassa boards represent Barelvi, Ahle Haidth, Shia and Jamaat-e-Islami schools of thoughts. Madrassas not registered with these wifaqs across the country are high in number, where thousands of girls are studying.

Interviews with religious scholars and researchers suggest all five schools of thoughts in Pakistan are running madrassas for both boys and girls. All of them experienced a surge in female students’ enrolment in recent years.

Allama Hafeezur Rehman Soharwardi, an administrator at the Jamia Faizan Aulia, a Barelvi madrassa where girl students study, says that because of preaching of the Dawat-e-Islami, an apolitical Barelvi religious campaign, trend of sending girls to madrassas among the Barelvi community has been increasing. "Nearly all madrassas now combine religious education with modern subjects to varying degrees and by doing this they are playing a major role in promoting literacy and awareness among Muslim girls," Soharwardi tells TNS.

Curriculum at madrassas is not the same for both genders and managers of madrassas and designers of curricula are men. However, girl students are taught and housed separately with all-female teachers and staff.

Mufti Qutbudin Abid, a religious scholar who runs a Deobandi seminary for girls in Karachi, says there are some separate chapters such as ethics and home economics in curriculum for girls. "Recently, we saw an increase in a number of higher degree classes in madrasas," Abid tells TNS. This year, 2,148 girls will appear in the examination of Darja Alima (equal to MA Arabic and Islamic Studies), as compared to 9,067 boys, statistics of Deobandi board shows. Girls exceed boys in their academic achievements at madrassas, with a greater number registering for graduate examinations and enjoying a higher pass rate, Abid maintains.

Analysts say there are several factors behind the growing number of female students from lower-middle and middle-income families in madrassas and they respond to many pressures resulting from economic, social and cultural change.

Jawed ur Rahman, a Karachi-based journalist, who covers religious affairs, says that madrassa education for girls brings many economic and social opportunities. "Along with the gathering of sawab for themselves and their families, madrassa education provides the option of taking up teaching profession or set up a small madrassa. These women have better marriage prospects and this education makes them more respectable in the society," says Rahman.

Madrassas for female charge fee ranging from Rs500 to Rs1,500 a month.

Farooq Siddique, a researcher pursuing a Ph.D degree in female education in madrassas, believes after the start of insurgency in Afghanistan and revolution in Iran in 1979, establishment of madrassas and enrolment of students both increased to a great extent. However, the largest increase in madrassa enrolment of children aged 10 was seen during the rise of Taliban in Afghanistan. "Madrassas promote conventional roles for women and students feel confident about their position in society," Siddique says.

Conversations with female madrassa students suggest the environment of religious schools disregard worldly affairs. Sahiba Gul, 22, a student in a Deobandi madrassa in Karachi, says madrassa education is fine, except when pursuing higher education in, say, fine arts. "Violence against women or sexual harassment is on the rise because women get influenced by Indian tv serials and replicate the tricks to persuade men for attention," says Gul.

Parents have their own views on sending their daughters to madrassas. Asghar says people encourage girls to enrol in madrassas "to ensure they not drawn into love affairs."

There is much focus on female madrassas after the crackdown on the Jamia Hafsa, the female madrassa attached to the Red Mosque in Islamabad, where 100 students died in February 2007 defending Sharia law.

A leader of Wifaq ul Madaris Al-Arabia, requesting anonymity, says they strictly follow the policy of not tolerating any sort of involvement of students and teachers in militancy. "It is the reason Wifaq did not register Jamia Hafsa this time," he claims.