Ali Kazim’s ongoing exhibition at Rohtas 2, Lahore portrays rupture in its actuality

Chinua Achebe’s first novel Things Fall Apart (1958), translated into many languages of the world, has the rare distinction of being translated into both Urdu and Punjabi. The Urdu version is called Bikharti Dunya while the Punjabi translation is published as Tutt Bhujj.

One needs to read these translations to determine their quality but, comparing the titles, it feels the Punjabi title is more suited to the content of the book. The story describes the way the old order of a colonised country faced the threat of transformation and annihilation; and the changes occurred with time which affected the culture, customs, politics and lives of ordinary people. One prefers the Punjabi title because, in contrast to the Urdu one that relates more with the disintegration of outside world, it includes the destruction of inner self.

Whatever happens outside does get reflected in our inner selves since it is man who is the measure of all things. It emerges in our expressions be they in the form of conversations, actions, literature, art or other creative forms. These are reactions to an externality that is divided owing to political, religious, economic and cultural factors.

This fracture appears in the work of Ali Kazim from his recent exhibition ‘…of Darkness and Light’ (being held from Feb 18-March 5, 2016 at Rohtas 2, Lahore). Instead of alluding to breakdown of social, societal and aesthetic spheres, the artist has portrayed rupture in its actuality. A visitor in the gallery is confronted with a large work on paper, composed of tiny pieces of a clay pot carefully rendered by the artist. In a meticulous manner, Kazim has drawn each part of that utensil in different shades of grey, so one starts imagining the site where this breakage took place.

However, the site is not away or detached from us because, in a culture like ours which survives on the cusp of tradition and modernity, the deterioration of values, customs and conventions is important on many levels. Mainly because it implies that in the present world, one does not need to refer or connect to history and heritage which in the opinion of many is not essential (late Salahuddin Mian had once declared: ‘Tradition belongs to the graveyards’).

At the same time, it unfolds the threat of erasing local narrative and regional practice in favour of global influences. For instance McDonald’s food represents a sign of modernity and the homogeneity of multinationals (although in each branch the standard food chain offers some local choices). Rather than affirming the multinational’s acceptance of multiculturalism, the addition of these ‘local’ flavours is more of an attempt to take over the traditional food or beverage for its business needs.

It seems that Kazim is concerned with this shift in a culture in which the past may not be revered as perfect; it is also discarded for superficial reasons. Because the loss of one’s identity is not a complete loss since it entails adaptation of a new identity. Although, ideally, one is free to choose one’s identity, in our circumstances one has to pick from the few options available which are not different from each other (like the contemporary scenario of politics in Pakistan in which it is difficult to distinguish between the agenda of one party and the other).

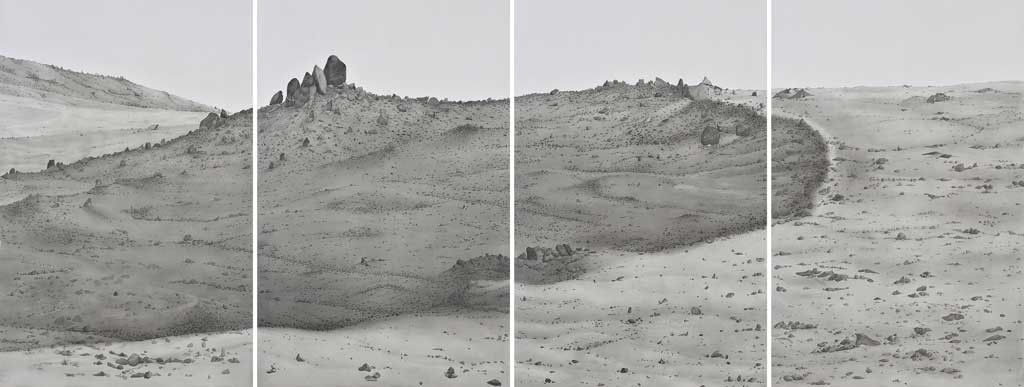

The disintegration of old order is represented in his work on paper but it has the same surrealistic feel that can be witnessed in other pieces from his solo show. For instance, large scale ink on paper drawing depicts stones on a field, two other small works portray sensitive elements of nature, i.e., clouds etc. In these works, Ali Kazim impresses a viewer with his skill by capturing the delicate texture and surface of a dust cloud erupting from the ground (Untitled Ruin Series I).

The same mastery of making is evident in his three dimensional works, which are clustered on the side of the gallery space. Looking like stones from the planet earth or moon, these vary in terms of their size and surface treatment. Immaculately manufactured, the work created in ceramics resembles the real stones but, on a closer look, one finds vein-like web and lines on these forms. Thus, on another level the hard, ancient and eternal stone turns into soft, palpable and perishable heart or other living organs.

The blend between the two perhaps is the key to comprehend the art of Ali Kazim because on the surface one glimpses a barren land (Ruins Series) but in essence these map human misery and situation. What scatters in the form of tiny particles of a pottery piece on a sheet can be a story of human existence (since it is the man who infuses and adds meaning to all that surrounds him!).

Arguably, the most exciting part of the exhibition is the work in earthenware ceramics, titled Fallen Objects; as these objects link the ground beneath one’s feet to heavenly bodies; especially due to the glaze on surface, these convey the impression of belonging to other planets. The work indicates a new dimension in the aesthetics of Ali Kazim, yet it is endowed with the same sensibility and sensitivity evident in his works on paper, especially in the Untitled Ruins Series I and Untitled Ruins Series II, both created with pigment on paper.

Interestingly the images, either two dimensional or in round, travel between a realm of imagination and reality, because the precision of execution makes a viewer believe in the actuality and physicality of what is presented; even though it is a figment of the artist’s fantasy.