Climbing 500 steps to get to Ranigat -- from where the queen used to enjoy the view of the vast fields

Visiting the Ranigat relics at Buner brings the past to life once again. Besides having ecological significance, Buner is a very historical district -- home to saints like Peer Baba and Deewana Baba.

The Ranigat site has the largest Buddhist monastic complex accessible from both Swabi and Mardan districts. Its unique grandeur speaks volumes on history and culture of the Gandhara civilisation.

Ranigat, a word of Pashto language, means the Rock of the Queen; where the queen or rani used to sit on a flattened upright rock on top of a hill in the Buddhist times to enjoy the view of the vast surrounding fields from a height. Located near Totalai and Khadu Khel in district Buner, remains of the Ranigat site often go unnoticed by many travellers unless they are informed by the locals. Our guide took us to the less explored historical sites. He brought with him locally prepared special kebabs though we had assumed that there would be no need because we had expected it would not take long to return. But things turned out to be different.

We travelled along a rural road amid a couple of small villages. As we moved on, the Ranigat hills appeared and here the guide told us that since the site was located on top of the hill we would have to climb stairs.

The vehicle was driven on the cemented part of a partially constructed road but a major part had to be covered on foot which involves climbing about 500 steps. After parking the vehicle, we put our muscles to test and started climbing the stairs passing through huge boulders. In response to our gasping and panting, the guide suggested we proceed in intervals to avoid exertion. The boulders were placed in order almost as if a conscious attempt had been made. The rest-intervals were also enjoyable because they allowed us the opportunity to appreciate the engaging bird’s eye view of the villages situated in the plains below.

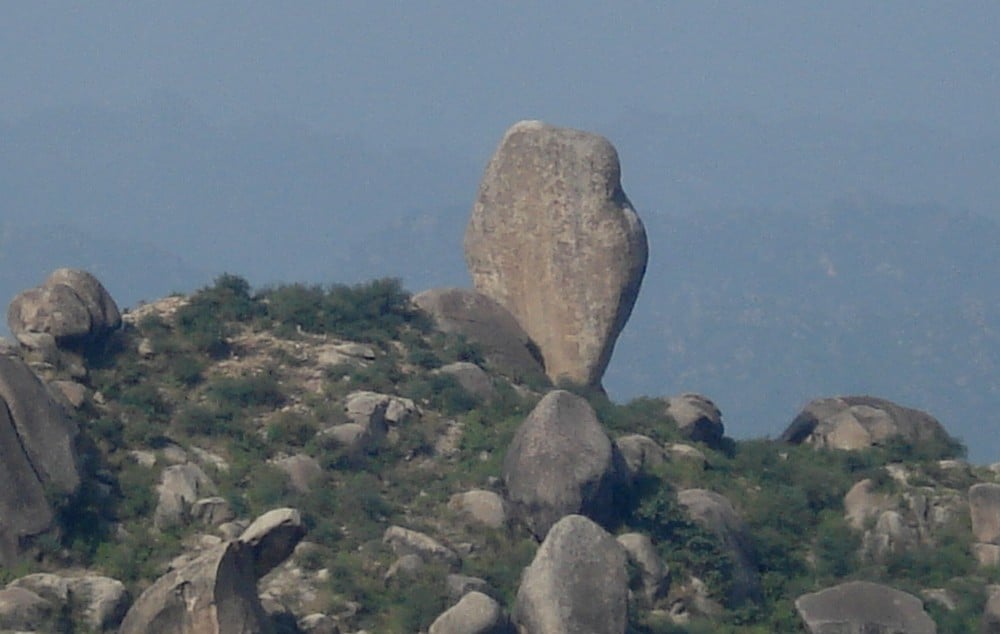

It takes almost 45 minutes to reach the top to explore the various archaeological remains of this Buddhist site. As we reached the top, the first thing we saw was the Rock of the Queen called Ranigat, surprisingly standing far away -- an upright flat projected stone with a height of over 40 feet. We were told that the queen used to sit on top of the huge rock to enjoy the rustic serene scene of the fields situated in the outskirts of the hill where wheat crops used to be grown. The steps that the queen used to reach top of the rock have been eroded.

We were also told about a local saying in Pashto which meant that the Rani used to stop people from hand threshing of the wheat because the rising particles or its dust used to be brought to the hillside by the blowing wind which used to contaminate the pure wind of the hills.

Just as one climbs to the top of the hill, the first structure that one observes is a small tunnel-like passage to the main compound where there are stupas and monasteries. While observing the monument, one marvels at the expertise with which blocks of rock have been transformed into masterpieces of masonry. The granite blocks are of considerable length laid properly in Flemish bond that attracts all. As we moved on, we observed more interesting places now shambled over time and damaged during Alexander’s invasion in 326 B.C. There is main stupas court; statues and pottery in broken form can be observed reflecting the events of the past. The area has been fenced to safeguard it from biotic pressure but time has taken its toll.

A bit farther into the compound, there is another area with huge boulders. There is a large boulder cut into a room about seven feet in height, with a small veranda-type space, a chamber with shelves for oil-lamps, a hole for ventilation or watch and ward. There is still the soot inside the rock-chamber. For a while, we were held in awe by the mastery with which a rock had been diligently cut and fashioned into a room-like chamber. Another similar rock structure is there with a den-type cut that must have been left incomplete or used for some other warding purpose.

On one side near the chambered rock, there was a small rock with a round large hole in it. The guide told us that just like a tandoor, this was used for cooking bread. Besides, there are small engraved sections for holding water used for cooking the bread. As we climbed, the rock view of the surrounding was merely spectacular. There was also a small deep line that ran across the boulder for rainwater harvesting. The remains are almost of the plinth level depicting sanctuaries and residences.

It was afternoon time and we were famished. The guide called for a lunch break, and though we found the kebabs to be a bit cold, they were exceptionally delicious. We sat under a shelter now built to facilitate visitors to enjoy the lunch in the company of the Chowkidar. All the time the Queen’s Rock, in all its magnificence, remained in sight, as if looking over from a place where no one would dare to climb because of difficult access to its top.

We also met some students who cross the Ranigat hills daily to come from the village on the other side to the school in Nogram village which is located at the foothills. We were compelled to think that these kids cover the hill twice a day from home to school and back which requires a great deal of stamina, to ascend and descend the hill.

Descending from the hill was easy and in a strolling fashion we kept moving discussing many aspects of the site while crossing paths with some visitors who had come for site seeing.