Female agency and male desire -- a look back at Arman, a 1960s blockbuster movie

In one of my recent columns, I had lamented the lack of agency exercised by female characters in Bin Roye; characters who were otherwise firmly grounded in modernity. I had also drawn attention to earlier movies with complex female roles.

Capitalism and modernity are not synonymous, but our contemporary sensibilities stem from feudalism’s lurch to capitalism -- both entrenched in patriarchal desires. Over time, the sense of identity has shifted from subject to citizen, forcing a sense of agency. For women and other minorities, the process has been one of pain without curbing the male desire to control female body.

Nevertheless, the process is irreversible. Cinema the most capitalistic of art forms due to the cost incurred, and thus drawn to entertainment, remains problematic because it is so male-dominated. The pressure of cost tilts it towards entertainment, away from art, shifting focus from empathy to identification.

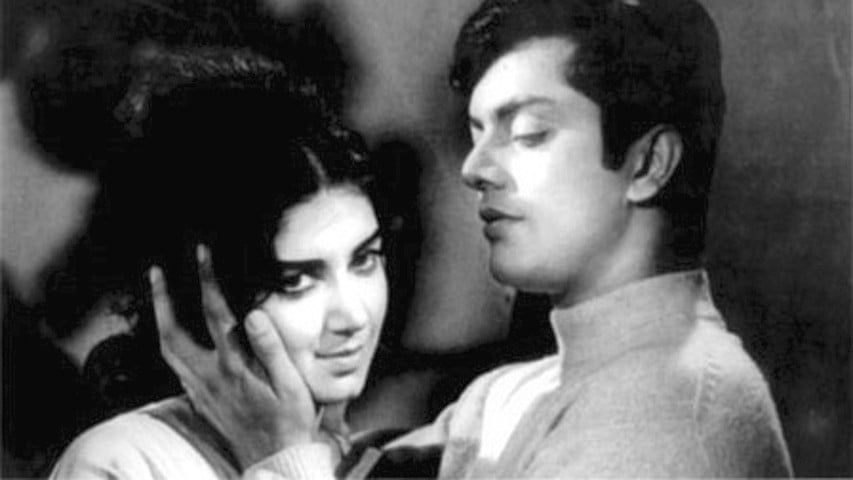

The Urdu movie, Armaan (1966), captures the tension between female agency and male desire superbly. The film opens with a nawabi milieu in an urban setting with women in control. Najma (Zeba) who is treated as a servant by a distant aunt is also of nawabi background. Seema, the aunt’s daughter, addresses Najma respectfully, like a sister. Seema is pregnant and doesn’t tell her lover Sohail that, lest he cancels going to the UK for a special reason. As the boyfriend takes off, Najma becomes the secret-sharer. The child is born and is being raised, under Najma’s supervision, in a nearby hut with a poor family.

Just as women had managed to be the arbiter of their destiny, the male desire -- in the form of nawabi feudalism -- re-enters the picture. Our hero Nasir (Waheed Murad) of a noble lineage arrives in town with a friend, the comedian sidekick trope (Nirala). Both switch roles, allowing Nasir proximity to Najma and they are in love. After a few romantic songs, feudalism flexes its muscles; the hero must marry. Nasir insists on getting married to Najma. The aunt has the boy produced and the caretaker places him in Najma’s arms. Seema’s earlier silence is transported to Najma’s lips. Seema watches with bated breath. Najma’s silence challenges male desire. Patriarchy punishes.

Najma’s silence is not weakness. A class issue, Najma must help her rich cousin. Our sense of the hero as a modern being crumbles. His mask of modernity is pulled, revealing a feudal tragedy. The woman he loves is not a virgin. As per male desire, the transgression must be punished. The clash renders the two women silent.

Najma is kicked out, though being supported financially by Seema. Being a single mother -- as if there were no single mothers in Pakistan in the 1960s -- Najma finds herself vulnerable (to lower class male lust). The film hints that it is not against sex outside marriage but feudal sensibilities are respected. The handling of the earlier expose of the daughter’s sexual transgression is handled delicately. No male character is allowed to pontificate. It is strictly a female affair. They know they are up against a decaying patriarchy and know how to navigate it.

But, the movie does not know how to engage with class issues. Nasir and Seema are now married. Najma murders her would-be rapist (read: male fantasy) and shows up at her cousin’s door with the child. Remaining within the constraints of male desire, the movie assures that Najma feels responsible for Nasir’s unhappiness while he -- a symbol of patriarchy -- renders himself useless by giving in to alcohol. Visiting bars to get drunk is not seen as a moral dive: the emphasis is on male sorrow.

Seema refuses to let Najma leave for multiple reasons. She cannot raise the child alone. Her inner humanity impels her to provide shelter for her cousin and, despite her husband’s sulking, she stands her ground. In the eyes of her husband, and her mother, Najma is a fallen woman, and yet a place has been created for her -- the woman who has transgressed -- right under the feudal roof, de-stablising male authority.

As the movie progresses toward resolution, Sohail the actual father of the child returns and is shocked to learn what has transpired. Though he’s lost his love, he wants his son. Nasir mistakes him to be Najma’s lover, but the misunderstanding is cleared when the two end up face to face, one with a pistol in his hand. Seema rushes in front of her husband to take the bullet in her chest instead. Sanity prevails as no shot is fired. Seema faints and in one of the queerest scenes on Pakistani silver screen, both the husband and the lover carry her to the bed. Just when you thought male desire had forgone its ego, and after the most repeated, and laughed at, lines from the movie are spoken by Nasir to his mother-in-law, "People of the world, salute Najma’s greatness!"

The mother-in-law in the next scene makes her final plea on behalf of male desire, to Najma to disappear to save Seema’s marital home. She obliges. The film cleverly exposes that even when men are willing to enter modernity, patriarchal traditions are strong enough to throw a monkey’s wrench.

Transgressors (especially women) must be punished during the course of nation building, a rule Mehboob Khan set in his classic Andaz (1949). In Arman female agency is allowed, even if to let Seema take her own life, to reassure male ego. Need I remind, patriarchy is bruised at this stage, but female agency too is compromised. As Najma departs, the cab driver turns out to be the (evil incarnate: read lower classes seen through an upper class lens) same person who’d tried to molest Najma. Not dead yet! His class notwithstanding, his maleness is patriarchy’s extension. During a chase scene, a symbol of modernity -- a train -- forces him to the river. Dead finally! Najma is spared (read: female perseverance), but she is on crutches. Sorrow-struck, Nasir hallucinates that Najma is playing hide -- and -- seek with him.

Only for once, the film establishes female power over male desire. She is discovered and brought to reunite with Nasir. In the end, a woman barely earns her agency but needs crutches. She is back to the man who disowned her. In Pakistan, we haven’t developed a culture of studying films politically as yet. Arman was made on the heels of 1965 war fiasco, masterfully turned into a hollow victory. The wounded male pride was restored with propaganda and patriotic songs like aye watan ke sajeeley jawano till the next foolhardy episode.

I wonder if the war’s destabilisation of male desire had any effect on the meta narrative of the film that plays cat and mouse with female agency!