What is wrong with the public art being produced in this country and why it is not likely to make an impact?

"In principle I mistrust all group acts and, therefore, those of artistic movements or schools. We know that a movement can be artificially implanted and maintained, with little or no meaning, without exercising the slightest influence on reality, which follows other conduits." -- Antoni Tapies

Nazi information minister Goebbles used to say that whenever he hears the word culture, he wants to reach for his gun. In a not too dissimilar manner, whenever someone says ‘public art’, one wants to search for something -- perhaps its meaning in our context. Like every other trend, borrowed and imported from outside (mainly the West), the idea of public art is gaining popularity in our art world. So much so that if you try to disagree with it, question its relevance, or critique its practice, you are bound to been seen as ‘public enemy’ number one.

Not only are you perceived to be against public, but against art, democracy and citizens’ participation. On one level, these acts and activities add into the small world of art practice in Pakistan, provide an opportunity to reflect on important questions on art, and extend a space for people to interact with art. On another level, these invoke the need to examine a phenomenon that is growing in our midst.

To start with, the question emerges: what is this need to do public art in Pakistan, compared to other regions in particular. In Europe, North America, Australia, Japan and several other countries from Asia, Africa and South America, states spend huge amounts in building art museums, public galleries and introducing art in elementary education. In those countries, a visit to a museum on Sundays (a ritual that has replaced going to Church on weekly holiday) has become a norm. Along with that, news of exhibitions and programmes on art are given ample space on electronic and print media. Important names in art are familiar figures among the general populace.

In a situation where the value of art is established and supported by public and private funding, many artists seek to move away from this circle of state approval and private consumption -- beyond the world of galleries, collections and market. Thus one finds graffiti artists and performance artists who try to defy the established system of art and produce something that can not be purchased by a museum or private buyer. There have been numerous names in this regard, ranging from Keith Haring to Banksy, and Marina Abramovic to Tehching Hsieh, who in their works approach art as a temporal experience rather than a permanent object. (Although the works of Haring, once a graffiti artist, ended up as expensive pieces sold through the gallery!).

Here we do not have an art establishment to match with other places, so a gallery selling art works or an artist producing paintings and sculptures are still operating on the periphery of culture. Artists or sculptors doing any kind of work are credited for making people aware of the need of looking and appreciating art.

In that context, it seems extraneous to step out of gallery space and focus on public art because, in actuality, the public space is a carefully chosen arena where remnants of artists’ interventions are only valid and effective when these are documented and presented in a discussion on art at a gallery, art institution, seminar, conference or biennale. Otherwise in most cases, these efforts are wasted to oblivion, as today everyone appreciates Asim Butt’s stencilled scripts on the walls of Clifton in Karachi, primarily when these are printed in magazines and books; a passer-by on those roads hardly notices the existence of art works, notwithstanding their meaning or impact.

There are a few other examples of these public art pieces made by artists who are otherwise known for their works in acceptable genres. They enjoy great fame and prestige as successful artists after marketing their works through galleries and dealers, but feel compelled to do public art works as part of their ‘civic duty’.

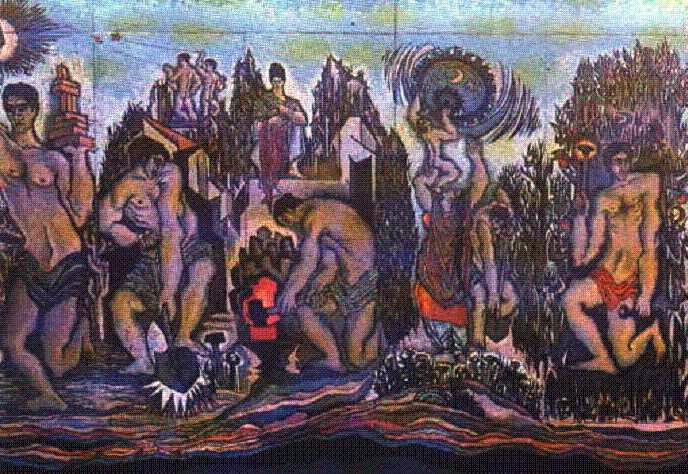

However, the matter is not so simple. Because what is created for private buyers is well thought out, cleverly composed, constructed with meticulous details while what is produced for the public is clearly a ‘comedown’ from the artist’s pictorial vocabulary. Though it is not worth purchasing largely because of the format, it is not valuable in terms of aesthetics quality. This difference of approach is a recent phenomenon because, if one recalls, the major artists of this country in the recent past did not differentiate between private and public art projects. Hence, Sadequain’s paintings on small canvases and his murals in Mangla Dam and other public buildings are hardly different in terms of imagery or painterly treatment.

Perhaps, this aspect of the painter’s position, in offering the same and profound imagery for public and private eyes, is the reason why the public is still connected to Sadequain’s art even though he never did a ‘public art’ project. He never made a distinction or segregation between his audiences, so his work regardless of its size, material or place, remained relevant for his wider audience.

Artists who take this role upon themselves to reach a large population always focus on a political message through their public projects. Somehow they believe that if they are not going to ‘educate’ people about gender equality, growing violence, sectarian intolerance or importance of peace, their efforts in going to public arenas would be seen as futile and frivolous.

In most cases, these artists are conscious of conveying a political and social message. They don’t know that if they try to be true to their ideas (which could be about issues other than politics) in their complex format as seen in the galleries, the public will respond to them eventually, in due time. Only when an artist tries to ‘descend’ to the level of people and produces a politically-charged work, it becomes a wasted endeavour. One can draw a parallel of this from the realm of poetry. Habib Jalib wrote politically-laden verses in a diction that was easily accessible to the public while Faiz Ahmed Faiz, in contrast, remained committed to high art, with its political undertones and sophisticated language. The discerning reader prefers Faiz over Jalib because like the lovers of beauty, the lovers of art are not loyal or kind.