When artists defy all ties and revel in a shared history

These days, gadgets come with manuals on how to operate them. Some people diligently follow the instructions while others rely more on trial and error or use their intuition to know the system and its utility.

Artists’ words also work like manuals: these are often perceived as keys to decode their ideas and imagery. These manuals or texts come in various forms -- manifestos, statements, lectures, journals, diaries or letters. Broadly they fall into two categories: some like manifestos, statements and lectures are produced for public consumption while others like journals, diaries and letters are addressed to a particular person or are meant for private viewing of the artist/author.

On reading all of these, one tends to question if there is a difference between private letters or public statements. Where is the truth? Does it lie in the exclusiveness of a letter or journal (often jotted down without much correction or editing) or is it in the manifestos and statements prepared for the public to proclaim the artist’s views and position on his art.

The matter needs a detailed investigation because, in many instances, what is inscribed as a manifesto or statement is a rehash of clichés and conventional phrases. Whereas when an artist shares his thoughts and creative process with himself or a friend or a fellow artist, he seems more honest and original in stating his intentions and formal concerns.

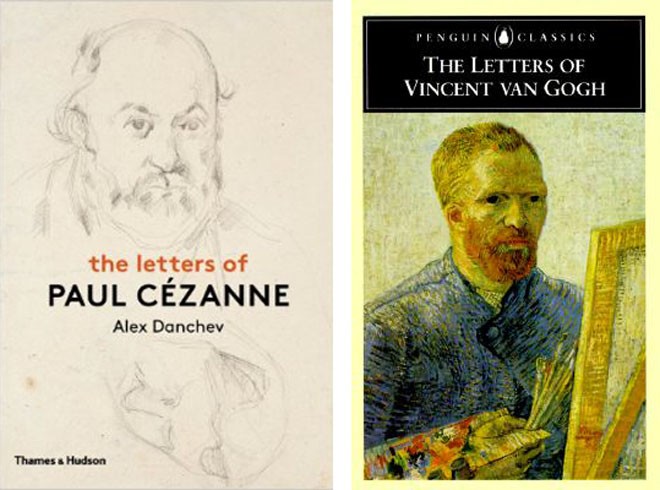

For instance, a lot of people do not recall statements made by Paul Cezanne but all remember an excerpt from his letter to the young painter, Emile Bernard, in which the French Post Impressionist advised him: "..treat nature by the cylinder, the sphere, the cone, everything in proper perspective so that each side of an object or a plane is directed towards a central point. Lines parallel to the horizon give breadth … Lines perpendicular to this horizon give depth. But nature for us men is more depth than surface, whence the need of introducing into our light vibrations, represented by reds and yellows, a sufficient amount of blue to give the impression of air". In fact, this part of his letter reveals his pictorial quests and aims more than any attempt of formal theorising by the painter. It also guided (along with his canvases) the younger generation of artists including Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque to create work that is defined as Cubism.

Another artist known for his extensive letters is Vincent Van Gogh, in which one comes across the painter’s life as described by him to others. Without being self conscious, he discussed a creative personality’s problems which are shared by several other artists. Thus the words of letter addressed to a particular respondent become relevant for many, those who lived in his time, and of latter periods too. Through these one can discover the intricacies of a mind which, contrary to general assumption and popular perception (that he was mad), was highly rational, sophisticated and coherent. Van Gogh in his letters disclosed a painter’s passion who was pursuing his search for ultimate truth in a constant struggle, which included the crisis of physical survival and question of solving aesthetic complexities.

In one of his letters, he explained this dilemma: "So I am always between two currents of thought, first the material difficulties, turning round and round and round to make a living; and second, the study of colour. I am always in hope of making a discovery there, to express the love of two lovers by a marriage of two complementary colours, their mingling and their opposition, the mysterious vibrations of kindred tones."

This brings one to the matter of a link between the world and word. If one ignores the presence of letter L, perhaps there is hardly a difference between the two. Because for a human being what exists in his surroundings is immediately -- and without plans -- translated into his thoughts. The thinking phenomenon comprises a linguistic process; so in a way all of us are translators, constantly transforming reality into the realm of language. The structure of a language is said to shape and compel our perception of the world around us. For example, we domesticate (or tame) exotic plants by renaming them to vernacular diction or merely adopting the foreign names.

In the world of visual art too, once we are exposed to concepts, techniques and materials which are alien to us, we are inclined to familiarise these by adding an indigenous colour or cause. In this context (or so-called contest) of local and outsider, Shakir Ali attempts a universal view by stating: "For an artist, it is necessary to know his link with his society and background, so he realizes his intentions, which must always be approached in a certain context. As far as I am concerned, I often feel that in this cycle of life and death I was born sometimes in the period of Altamira Caves. It seems to me that I spent my life with people of that period, and made paintings. Then I think that may be I was born in Crete and was one of the dancers in front of the Sacred Bull and was doing paintings on the walls with them. Or perhaps I was amongst those who lived in the period of Akhenaton and painted Nefertiti. Or may be I was at Ajanta Caves".

His words show how an artist from the 1960s was connected to a larger and longer tradition of image-making that connected an artist’s expressions to the universality of art experience, long before the wave of political correctness and purity.

Many other artists through their words or pictorial practices have defied their ties with a single society, as they were more interested in a shared history. However, more than the matter of territorial allegiances, artists are also interested in showing and sharing their affinities with their studios and the act (and pleasure) of art making, which liberate them from all limitations -- including the divide between word and image, indigenous and imported, and more importantly our grasp of a uniform or immediate (geographical) reality.