A commendable work that puts together the interviews of some famous Indian film directors

Karl Bardosh says there are three kinds of film directors in the world, viz. craft, mise en scene (placing on stage) and auteur (author). Craft directors direct non-narrative programmes like reality shows, commercials, web videos, etc. Mise en scene directors deal with the narrative storytelling like television series and feature films. Auteurs like Charlie Chaplin, Jacques Tati, Roman Polanski, Alfred Hitchcock, Woody Allen and others comment on the universe and the human predicament. The Westerners have a long history of teaching filmmaking whereas India’s filmmakers have thrived on a self-taught method coupled with creativity.

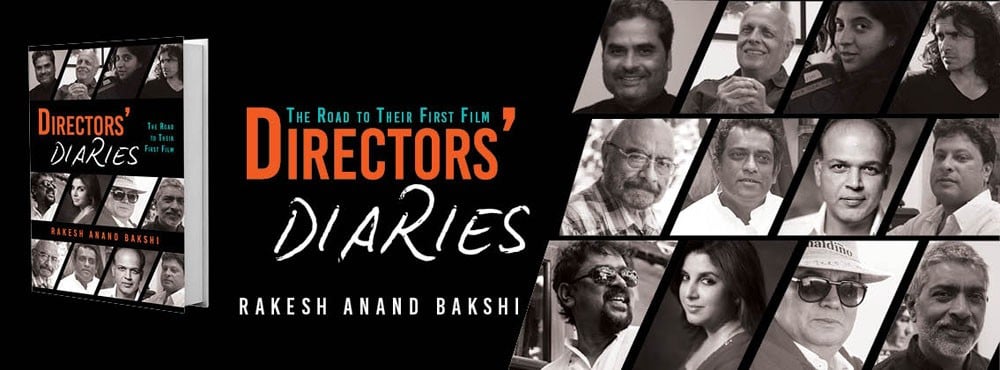

When Rakesh Anand Bakshi, son of the lyricist Anand Bakshi, read that David Lean, the director of Lawrence of Arabia and Doctor Zhivago, used to be a tea boy in youth he thought of recording the experiences of some directors of the Hindi film industry. His book Directors’ Diaries is about the challenges, odds and hardships that twelve Indian film directors faced before they realised their dreams. The book starts with an exhaustive interview of Anurag Basu and ends with that of Zoya Akhtar.

Anurag Basu from Chattisgarh was a sales representative for electric switches and plastic chairs, background dancer and third assistant cinematographer as focus puller. He directed TV shows before directing his first film Saaya in 2003 and Barfi in 2012. For him "filmmaking is like entering a dark tunnel with a small torch…" Anurag’s knowledge of camera, his storytelling ability, his talent as a screenplay writer, his ability to express himself, his simplicity, his respect for technicians and his humility are worthy of note.

Ashutosh Gowariker of the Lagaan and Jodhaa Akbar fame acted in plays during his college days in Mumbai. He believes that one can understand an actor’s emotional space through empathy. His catchwords are: preparation, perseverance, patience.

Farah Khan, born in Mumbai, began dancing when her father died and assisted Shankar Nag on the TV series Malgudi Days. She learnt dubbing, mixing, remixing and other things connected with filmmaking. It took her seventeen years to direct her own film. She is witty and has a tremendous sense of humour. She enjoys reading novels, writing and directing dramatic scenes. Michael Jackson’s Thriller reignited her passion for dance. She dropped out of college before graduation, qualified for the World Dance championship and wanted to assist a filmmaker.

Govind Nihalini migrated from Karachi to Udaipur in Rajasthan in 1947. After a diploma in motion picture technique in Bengaluru in 1962, he started his career as an intern to the legendary V.K. Murthy of Guru Dutt’s Pyaasa and Kaghaz Ke Phool fame. He cinematographed fourteen feature films. His first film Aakrosh is based on a real event narrated to him by Vijay Tendulkar. Tamas was the result of the impact of the partition experiences, fear, panic, the sight of blood and curfews on his consciousness. For Govind Nihalani characters are more important than the plot although a good narrative creates good characters and visions. The temples of Udaipur, the magazine Kalyan, Udaipur Public Library and Kanhaiyalal (a still photographer) are the great influences on him. He liked the cinematography of the films, Lust for Life and Red Shoes. But it was Murthy who changed his life forever and taught him that the intensity of the image is important, but the intensity of the emotion a cinematographer arouses in the viewer is more important.

He spent his time in the company of Shyam Benegal, Girish Karnad, Satyadev Dubey and Vijay Tendulkar listening to their views on socio-political issues, literature, history, economics, etc. Ritwik Ghatak taught him the value of silence in cinema. He studied the films of Ritwik Ghatak, Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen and others thoroughly. A book on scriptwriting by Vsevolod Pudovkin taught him the value of transition from one shot to another, a forward thrust for the narrative. For Govind Nihalani, the human face is an emotional landscape of the character. That is what Om Puri does in Aakrosh; he doesn’t say anything.

Imtiaz Ali worked for tv for seven years till he made his first film Socha Na Tha followed by Jab We Met, Love Aaj Kal, Rockstar and Highway. He is an excellent narrator of stories. His memorised narration of each script lasts between one or two hours without referring to any script. His childhood was spent among the Indians of various cultures. He developed the cinema habit because he was ‘a bad student’ and failed. He started doing theatre, elocution and writing. It was a total transformation. Rejection made him very strong.

Mahesh Bhatt was born in Mumbai in 1948 to a Hindu, Nagar-Brahaman, Gujrati father and a Shia Muslim mother. His father, Nanabhai Bhatt, was a filmmaker and his mother an actor. But they were not married by the standards of the world. His father was married to a Hindu woman, who was his legal wife. Johny Bakshi changed his life and he realised that the film world and the real world were two different worlds. One learns filmmaking by making films. He believes that the real story is hidden in the unsaid, that the film institutions polish pebbles and dim diamonds. Emotional literacy is needed for films not film schools. He stuck to his beliefs and convictions while filming Arth, Saaransh and Zakhm.

Prakash Jha wanted to be an artist. He left his village for Mumbai and decided to be an assistant director to Chand who was directing Dharma those days. His father was so upset that he remained separated from his family for five years. He worked in a restaurant on a salary of three hundred rupees per month. He did a course in film editing and after ten years directed his own film. At FTII (Film and Television Institute of India), he learnt that editing was the most important skill in filmmaking. He was studying at two places at the same time. So he would bring meals from the restaurant for his teachers who would do him a favour by marking him present. He knows how to merge art with commerce and make a film as a medium of social change. He comes from a family of landowners and farmers. It helped him in directing his Damul.

Santosh Sivan was born and brought up in Kerala where he assisted his photographer father during school and college years. He graduated from FTII, Pune. For him, still photography is the best way to begin with. And cinematography is an extension of photography. Visual art is learnt through self-discovery. He learnt to study changes in the light in childhood. He loved the dance, music, culture and stories of his village. He learnt many things by observing people in front of the still camera. He shot documentaries and feature films. He directed Halo, The Terrorist, Asoka, Tahaan, Inam and other films. His philosophy is: "Worship light".

Subhash Ghai was born and brought up in Nagpur and Delhi. He too studied at the FTII, Pune. He incorporated his experiences in his films, along with his culture, dreams and unrequited aspirations. His well-educated family migrated from Pakistan in 1947 and faced financial and emotional crises in Delhi. He developed taste for music by listening to bhajans in an Arya Samaj Temple. When he grew up he saw the films of Godard, Fellini and David Lean. He loved the films of Bimal Roy, Mehboob Khan and Raj Kapoor and learnt the importance of sound, image composition, editing and lighting from Ritwik Ghatak. He became a writing assistant and learnt the texture of screenplay writing. One day N.N. Sippy heard his story Kalicharan and was so impressesd by it that he asked him to direct it. That was the turning point in the life of Subhash Ghai. He made nineteen films and sustained himself as a director for forty years. He founded a global film school, Whistling Woods International where students evolve, grow and rediscover themselves as artists and humans.

Tigmanshu Dhulia was born in Allahabad, studied English, Economics and modern history in the university, saw action movies, learnt acting at the NSD, translated plays into Hindi, wrote dialogues for Mani Ratnam’s Dil Se, saw many plays and was assistant director of Shekhar Kapoor’s Bandit Queen. He is poetic when he writes dialogues, is honest about the craft and can shoot for sixteen to seventeen hours without a break.

Vishal Bhardwaj wants the audience to question him, themselves, society and the state through his films. He was born and brought up in Uttar Pradesh, spent a large part of his childhood in Meerut and did his college education in New Delhi. He played the harmonium at food festivals at Pragati Maidan. From a music composer he turned into a film director. He made Makdee because he wanted to fight superstition. Though he has roots in UP, he considers himself a rootless person. He did not go to an English medium school for the elite. He developed friendship with the poor slum kids. He witnessed Hindu-Muslim riots which affected him deeply. He read detective stories, Hindi novels, Ayn Rand, Irwing Wallace and Urdu poetry. For some time he wrote poetry and short stories, found it difficult to memorise history lessons, so he composed his history lessons in metre as songs, sang them and passed the examination. Usha Khanna encouraged him to be a music composer for films. With Gulzar he went to film festivals. The Polish film director and screenwriter Kieslowski, who made the trilogy Three Colours influenced him.

He came to Mumbai in 1990 to become a music composer only. He composed music for Maachis. Extensive readings were done for Maqbool. Naseeruddin Shah conducted those workshops for him. Maqbool, Omkara, 7 Khoon Maaf, Matru Ki Bijlee Ka Mandola and Haider are some of his films.

Zoya Akhtar, born and brought up in Mumbai, studied literature and sociology in college, was assistant director on Mira Nair’s Kama Sutra, did film production diploma from New York University and directed her own films. Her parents and mother’s sisters are in films. She spent her childhood in the company of film personalities. She decided to direct films after watching Salaam Bombay.

Rakesh Anand Bakshi has done a commendable work by compiling and editing the interviews of twelve Indian film directors in his book Directors’ Diaries. It has taken him many years to complete the job. He knows very well what he wants the filmmakers to say and share with the readers especially those who dream of directing films. He is clear about his inquisitiveness and aim: he himself learns while listening to the experiences of the filmmakers. His language is clean, pellucid, simple and chaste.

I found some questions repetitive. Clichés spoil questions, answers and writings. I have a personal grudge against the question: ‘What is your message to the youth?’ The work done by an artist is his message to mankind. Many questions could have been deleted and replaced by interesting ones. It is a must read for beginners in filmmaking and general readers.