Are the artists doomed to remain trapped in their ‘lived’ experience or can they transcend it?

"I believe that our tradition is the whole of Western culture, and I also believe that we have a right to this tradition, a greater right than that which the inhabitants of one Western nation or another may have." -- Jorge Luis Borges (The Argentine Writer and Tradition).

The Indian author Vikram Chandra recounts an incident during a literary conference in New Delhi. In the Q&A session, a professor amongst the audience asked an expatriate Indian novelist writing in English, as to how could he pick subjects, settings and characters from a land which has little or no connection with him, as he is living in faraway Australia. Chandra responds that the comment came from an Indian who had studied English poetry of daffodils and wrote critical essays and analyses on novels about London, a place he had never visited.

Preference for one’s own literature owes itself to association with one’s region. However, the fact remains that English language has opened up the possibility of reading millions of translated books.

This freedom available to a reader becomes a matter of concern when it comes to writers. It is expected and demanded from an author or artist to concentrate on reality in his surroundings in order to express his feelings, ideas and observations compared to a consumer of works of art and literature.

For instance, a person who decides to focus on the inhabitants of Alaska in his art or fiction without ever leaving his desert city of Bahawalpur would be considered odd because one immediately assumes a lack of authenticity and truth in his creation. Such a person is doomed to remain trapped in his ‘lived’ experience while trying to convert it into art.

Expectations of this sort are not limited to the choice of a subject; these extend to the matter of medium and technique too. A person who lives in a language is supposed to be writing in it, but there are various examples where writers made great contributions in languages that weren’t their mother tongues or first languages, like Joseph Conrad, Vladimir Nabokov and Milan Kundera.

Writers who belong to a culture that uses more than one language (one often imported or imposed) are often criticised for not preferring the vernacular. This may represent reality in its authentic diction as well as is understood by a larger/local population. Thus, there is always pressure on English writers from the subcontinent and Africa or French writers from North Africa to use their vernacular tongues in order to express themselves.

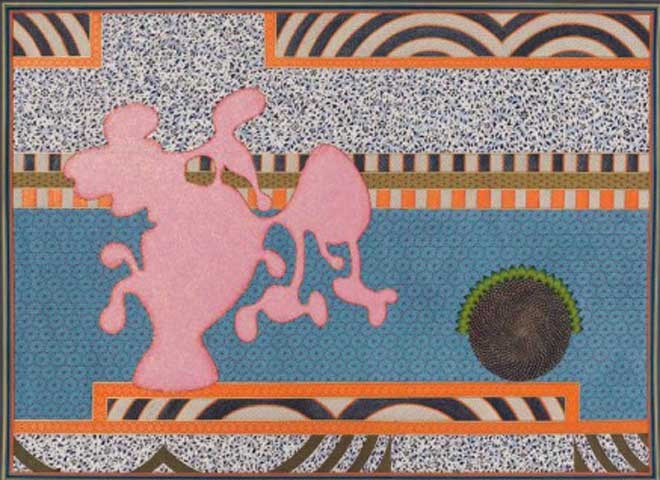

In a similar way, artists are also expected to employ forms, techniques and mediums that are associated with the tradition of a society -- like miniature painting in India and Pakistan, watercolours and calligraphy in China and Japan, Batik in Indonesia, and wooden sculpture in Africa. All these connections with culture, if not visible in the works of major artists, are seen in the way local artefacts are prepared.

Interestingly, tradition and the notion of tradition do not necessarily match. Many practitioners of modern miniature painting presume that conventional wasli paper was used for making miniatures in India and therefore use it, not realising that the paintings of Akbar-Nama, the first major Mughal opus, were executed on fabric mounted on paper. Likewise, many miniatures from Rajasthan were painted on large piece of cloths called pichhavai.

Ordinary people are always in search of grandeur in the guise of tradition, like concocting an aristocratic family history or noble lineage. But sometimes it has also compelled artists to keep glued to their culture and heritage. Sometimes the confines of cultures are so strong that even a person who is not living in that location uses the imagery, themes and concerns related to his abandoned homeland.

There are two kinds of creative individuals when it comes to the issue of cultural geography. There are those who have this sense of freedom to express their ideas and imagery without feeling the need to be tied to their place of origin. This makes it possible for a French writer Julien Columeau to come to Pakistan and write fiction in Urdu, or a local artist Taniya Suhail to get trained in Chinese painting, come back to Lahore and create works in that style. Likewise, various artists have moved away from their regional limitations, once they are making still life or purely abstract paintings, which could be from any location.

On the other hand, some artists focus more on their national connections and cultural heritage. They feel the need to own their long lost ‘link’ with a place and often try to claim it for the sake of finding legitimacy in their adopted countries and privilege in their abandoned homelands. This urge to own and reclaim one’s connection with one’s forgotten place or past does work as a marketing strategy for some. An artist living abroad can produce something exotic based on his tradition to his immediate audience. Once the prodigal son comes home, he can present his work that now has the stamp of approval from outside and provide an occasion of pride and pleasure to the locals who identify with the cultural conquests of their celebrated compatriot.

Lately, the structure of nationhood is going through a crisis. Today our liberated elite, sick of those dated notions of nation state, is involved with celebrating the city. Thus there are attempts to market Lahore, Karachi, Multan, Mumbai or Mombasa as the newly-converted national identities in the name of metropolises. Just as the emphasis has shifted from country to city, may be in the coming years, it would evolve to affinity with neighbourhoods or even roads. To start with, we must brace ourselves to honour the cultural identity of Samanabad, Model Town, Gulberg and Johar Town in Lahore or Defence, Clifton, Bahadurabad and Bath Island in Karachi.